Looking at internalized racism through different lenses

February 4, 2021

Although the ongoing struggle with racism in this country has reached the forefront of national news several times during the past four years, it has been in the forefront of millions of individuals’ minds throughout their lives. Racism and racist stereotypes play an obvious role in this country’s politics, law enforcement, places of work, entertainment industry, and how people relate to one another. Therefore, the fact that racism and stereotypes present itself in classrooms and extracurricular activities at East and clearly impacts students’ lives even as we celebrate the remarkable accomplishments of Martin Luther King, Jr. should not be surprising.

Racist stereotypes are so embedded in American culture that many individuals do not recognize their existence or understand why certain beliefs may be offensive to certain groups of people. Any broad blanket statement about an entire ethnic group is generally not only inaccurate with regard to large numbers of individuals within the group, but also offensive. We are familiar with these gross generalizations because they show up in comedy and in the assumptions that we and our friends and families make about other people. Students at East have felt their cultures demeaned by such generalizations, regardless of whether the intent was malicious or simply insensitive.

With the uptick in hate induced violence and deaths throughout the country, the Black Lives Matter movement demonstrations, the messages conveyed through the flags and sweatshirts of the participants in the break-in at the U.S. Capitol, many people are becoming more aware of the prevalence of racism throughout the country. To help sensitize the East community to the subtle racism that exists among us, yet is still harmful, several Eastside staff members show through unique perspectives that this touches every one of us.

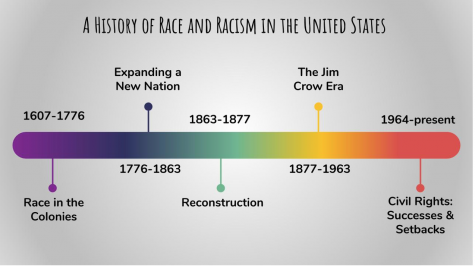

History of Racism

The racism that we experience and see evidence of today in America traces its roots back to a time even before this country was founded. By the time America established its independent government and Constitution, racism was so entrenched in the culture and economy, that almost 250 years after America declared its independence, this country is still struggling to cleanse itself of racism. Shootings in synagogues, police brutality and killings against African Americans and evidence of racism in the clothing and flags displayed by the rambunctious mob that broke into the Capitol building recently demonstrate racism remains instilled in our society.

Dating back to the mid 16th century, approximately 12.5 million were kidnapped from Africa and sold as slaves in America. These individuals were forced into hard labor, often receiving undeserved punishments. Families were split. Living conditions were deplorable. They were treated as property and not as humans. Those who attempted to escape were severely beaten or killed.

These crimes against humanity benefited white, wealthy landowners. Slaves would produce crops that were traded to bring additional wealth to the landowner. These landowners received all benefits, the protection of the laws, and were active in politics and government. While the economy and the laws were meant to benefit these individuals, America developed a culture of disparate treatment based on skin color.

America’s Constitution memorialized the prejudicial belief and made it impossible for African Americans to be treated as equals. Originally, the Constitution counted African Americans as ⅗ of a person for the purpose of determining Congressional representation. Many of those in government had no intention of freeing the enslaved and engaged in heated debates in Congress, trying to spread slavery to new American territories.

Even after the Northern free states defeated the Southern slave states in the Civil War, a large percentage of the population including individuals involved in government stayed true to their racist ideologies. A hundred years after the Civil War, African Americans still had to contend with Jim Crow laws that prohibited them from attending the same schools and businesses as white individuals.

Against this long-standing backdrop of hatred and demeaning treatment, Martin Luther King Jr, a minister and activist, instilled hope and lit the path for change toward civil rights and equal treatment for African Americans. Through peaceful protest and marches, he spread awareness of the biased and unjustified system in America. Even though he was consistent in his message of non-violence, he himself was the target of much violence, having had his house firebombed and surviving a stabbing attack before he was assassinated. Martin Luther King Jr.’s work led to important laws that gave African Americans the right to vote, ended segregation in public places, and ended employment discrimination based on race.

Now, over 50 years after Martin Luther King Jr. left his mark on American history, racism still drives many people’s behavior in America. While racism has continued to exist throughout many institutions in America since Martin Luther King Jr’s time, incidences of racial injustice and violence have increased over the past four years. The Black Lives Matter movement was established in 2013 to address the inequity in how law enforcement treats African Americans suspected of criminal behavior compared to how the system treats white Americans in the same position. During its marches over the past year, demonstrators on behalf of the movement were sprayed with chemicals or killed.

In the attack on the US Capitol that took place January 6th, the domestic terrorists made clear that they not only supported President Trump’s political ideals, but their deep-rooted racist thinking. Television cameras have repeatedly shown that at least one insurrectionist carried the Confederate flag, promoting the atrocities of the slave system. Another, was shown advertising Nazi propaganda.

Despite celebrations that may take place on Martin Luther King Day and throughout Black History Month, racism remains a contentious issue in America that must be resolved.

Asian Racism

How COVID-19 has affected Asians

Not only has the coronavirus brought a slew of at home concerns and health issues, it has also triggered the onslaught of racism towards Asians. With China being the origin of COVID-19, it has sparked an increased amount of racist actions. While stereotypes perpetuated in mainstream media and everyday school settings have been constants, they have risen to an all-time high during the pandemic.

It is safe to say that coronavirus has impacted every aspect of our lives, including the very fabric of our society and the increased tensions towards Asians. COVID-19 has not only planted a seed of doubt in everyone’s minds that whispers, “Do they have covid?” but it has also dug a deeper hole for racism to be pitted against asians.

A student (‘23) states that when the first case of COVID-19 was discovered in Camden County, two of her classmates told her their parents encouraged them to stop talking to Koreans.

“They asked me if I had covid since I was a Korean, which was one of my first experiences with racism relating to the virus,” she explains.

This is not an isolated event. For Jaden Vo (‘23), he also faced racism-rife insults.

“I was sitting at my desk, and someone told me to go back to China since ‘I brought the virus,’” elaborates Vo.

This is the hard truth that many people have discovered during the pandemic. If someone is Asian, that does not automatically mean they have the virus. The origin of COVID-19 does not determine the status of someone’s health.

“Many students also called it the Chinese virus, and people at stores would noticeably distance themselves from me and…cough aggressively,” adds Kristen Eng (‘21).

Racism stemming from coronavirus has infiltrated everyday situations, and Darren Zhou (‘22) includes how his grandparents felt uncomfortable on the subway, and his parents advised them to minimize going out to public places.

“There is a…greater pressure on Asians,” explains Zhou.

The idea that COVID-19 is the fault of millions of Asians is incredibly harmful and misleading. These insults are normalized, and we must try our best to be kind to one another. After all, we have all been affected by covid, so why can’t we unite ourselves?

Misconceptions of East Asians

The East Asian stereotype. What comes to mind when this term is mentioned?

A student walks out of AP Calculus, a pencil in one hand and a calculator in the other. “How was the test?” his friend asks. He shrugs and explains it wasn’t too bad. A group of friends walks by, rolling their eyes at the response.

“Of course it was easy for you. You’re Asian.”

This long-lived term that has had a spotlight in TV shows, movies, and books is not just something for readers and movie-goers to get a laugh from. Let’s take a closer look at the expectations many East Asian students are held to every day by teachers, friends, classmates, and most of all, parents. The East Asian student stereotype, as explained by Asian students at East, is a hard-working student with yellow-tinted skin, narrow eyes, large-framed glasses who excels in academics and extracurriculars.

The stereotypical East Asian student also plays either the piano or a wooden box (small, medium, or large) with four strings that belong in the school orchestra. They apparently also love math and have no trouble with it at all. Just one question from the actual East Asian student community: who built this box Asian students have to somehow fit into? Because it sure wasn’t the ones who are held accountable for it.

“Stereotypes, in general, are based on some sort of truth, otherwise they wouldn’t exist. So, it’s true that some Asians typically do well in STEM courses or standardized tests, but it doesn’t mean that all Asians should be held to this level,” says Ethan Lam (‘22), a member of East’s Chinese Student Association.

So, how did this term come to be in the first place? It’s often very common in many Asian cultures to work hard and reach success. Many East Asians are raised with this mindset of putting in time, effort, and energy to achieve something in life, and to encourage their children to share that mindset as well. With this passing down of culture, which can be compared to the mere passing down of food traditions, many East Asian students today still hold true to this statement.

Though one may examine this mindset formed by culture and find East Asian students to be in a particularly stable position where the people around them support them undeniably, which would seemingly make it easier to succeed in life, it should not be sugar coated.

Katherine Li (‘23), a member of East’s Chinese Student Association, says, “[The East Asian student stereotype] can put a lot of pressure on Asian kids.”

With a culture focused on success comes expectations for the young generation of those cultures, which results in pressure to work hard and exceed in school and extracurriculars. Expectations from parents to manifest the mindset rooted in their culture and expectations from classmates and friends to fit the East Asian stereotype of being smart naturally places quite a lot of pressure on Asian students. These expectations result in Asian students feeling as though they succeed not because of hard work, but because of their race, and that their excellence shouldn’t be celebrated upon because it’s expected.

Even though there are indeed select East Asian individuals who show this term to be true, not all East Asian students should be held up to this stereotype and standard. Just like with different types of people who enjoy cooking rather than reading, not all Asian students excel at math and are naturally good at coding, and they shouldn’t be expected to be.

“I know someone who is extremely smart and studies hard, but that’s not all that there is to that person,” says Sehoon Kim (‘23), a member of East’s Korean Culture Club.

East Asian students who are good at math should not be identified by a stereotype because there is more to their personality than what a stereotype holds. Similarly, East Asian students who have not played piano for six years should not be associated with not being “Asian-enough” because there is much more to their identity rather than not fitting a stereotype.

The term “East Asian stereotype” is so well-known that when said, an image of a whole being with a personality and life can be created in a human brain within seconds. However, it doesn’t mean that it should be normal for Asian students to feel pressure due to a stereotype. East Asian students are unique individuals who have different passions and interests, just like other typical high school students, and shouldn’t be held to collective preset standards in the minds of the people around them, whether positive or negative.

The media uses stereotypes to degrade South Asians

For years, degrading stereotypes in the television media has precipitated internalized racism against South Asians. Television shows typically provide people with entertainment, but even if discriminating against South Asian actors is intended for comedic purposes, those prejudices and ideas easily translate into real life experiences and encounters.

Comparatively, this dilemma presents itself in Disney’s sitcom “Jessie,” a show about a nanny’s experiences with three adopted children. As children watch these television shows, the characters and their actions greatly influence their views on a certain race. In the sitcom, actor Karan Brar plays a young Indian boy named Ravi. However, as much as the South Asian audience must have appreciated their racial representation at first, they quickly realized that the show disparages Indian culture by relentlessly using Ravi for comedic relief instead of honoring his Indian heritage.

For example, when the sitcom persistently satirizes Ravi’s thick Indian accent, this belittles South Asians in the media because the tormentor receives laughter and approbation for scorning South Asian culture. Also this representation condones these actions in society. Not only did the show ridicule Ravi’s accent, they also mocked his clothing, for example his traditional clothing of a ‘kurta,’ which is worn all throughout South Asia, not just India. Also, the sitcom created another joke when they cast Ravi with a pet lizard named Mrs. Kipling. Even though the television show is meant for entertainment, the name Mrs. Kipling markedly refers to Rudyard Kipling, author of “The Jungle Book,” and known as a staunch imperialist. Was the name choice truly for comedic purposes if a South Asian character owned a lizard named after the man who wrote “The White Man’s Burden”? This does not seem like a coincidence, and instead exactly like internalized racism.

Another prime example is how the television show “The Simpsons” propelled internalized racism for South Asians when non-Indian voice actor Hank Azaria played a demeaning Indian-American immigrant stereotype. Azaria plays Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, who runs a convenience store, and his artificial Indian accent along with his notably long last name specifically mocks South Asians who have names that Americans may have trouble pronouncing.

To make it worse, the sitcom characterizes Apu as stingy and penny-pinching, as the show exhibits him conserving the food by altering the expiration dates or brushing off food that fell on the ground so he can make profit off of the item. Also, according to NPR, the audience observes Apu manipulates and coerces his customers to buy items on various occasions. Some people may not have known about this stereotype, but this media brings light to it through satire.

Similar to Ravi’s character acting as an example of internalized racism for a younger audience, Apu’s character contributes to the degrading stereotypes for South Asians for an adult audience.

After voice actor Hank Azaria realized how negatively impactful this stereotype could be, he stopped voicing the character. In an interview on the “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” Azaria acknowledges the problem with Apu’s character, saying “The character had unintended consequences for people – kids growing up in this country, Indian and South Asian kids growing up in this country had to live with that character and be called Apu in ways they didn’t appreciate.”

He listened to criticism of the racist character and he realized why the American South Asian population condemned his character as offensive. Noticing this, he decided to step down from his role. Although this is a positive aspect of the situation, the fact still remains that he did not even notice the harmful impact the character may have had on judgements and stereotypes in society. This proves that racism towards South Asians needs to be carefully taken into account in the media.

Essentially, producers as well as audience members must recognize this persistent degradation against South Asians in the media and work to honor culture instead of devaluing it.

Without a doubt, internalized racism for South Asians in the media urgently needs more attention.

Personally, I connect with this persistent internalized racism and people must know: ridiculing South Asians should not be used for comedy in the entertainment industry.

Embracing our Asian roots

What does your culture mean to you? You may automatically associate food and holidays with the word “culture”. However, for many East students, culture is much more than the foods they eat or the holidays they celebrate; it is a part of their identity. Culture is something that individuals find pride in and share with others. Lalitha Viswanathan (‘22) and Benjamin Xi (‘23) are members of Indian Culture Society (ICS) and Chinese Student Association (CSA) respectively whose experiences with being Asian helped them fully-heartedly embrace their Asian culture.

“People would say I’m not South Asian enough because I don’t speak the language or go to Temple every week,” said Viswanathan. “I feel like it shouldn’t be stigmatized.”

Viswanathan is a second-generation Indian American who was raised in a household that did not speak Tamal, her native language, regularly. Feeling disconnected from her culture, she reflected on her cultural ties to her own Asian culture.

“My native tongue and not knowing the culture were the two biggest things that I think that I’ve kind of missed out,” explains Viswanathan.

During quarantine, she has been able to self teach herself Tamal and immerse herself in Bollywood movies. She feels that there is no set amount of culture that an individual needs to feel accepted in the Asian community. ICS and high school gave her the opportunity to surround herself with others that related to her. By doing so enabled Viswanathan to love her culture instead of suppressing it.

Xi strongly believes that it is important to appreciate your culture and find positive ways to represent it.

“I feel like ignoring my culture would be keeping a part of myself hidden from other people,” said Xi.

Xi, a first-generation Asian American, was able to appreciate his Asian roots at a young age. Like Viswanathan, he does not speak his native language fluently, which he feels is okay.

“I feel like my culture is a key aspect of who I am,” expresses Xi. “I don’t think I need to know Chinese 100% to feel connected to my culture.”

Reflecting on elementary school, Xi recounts racist actions that his classmates would do in the third grade. Being nine years old at the time, Xi did not know this action represented racism. Kids would pull their eyes back in such a way as to mock Asians. Even though his classmates would not do this directly to him, Xi finds the memory saddening to look back on.

For Viswanathan and Xi, culture is a major component to their identities. Culture goes much deeper than the surface of food and holidays; it opens the door for discussion, self-expression, and representation. Now take a few seconds to reconsider the question: What does your culture mean to you?

Racism in Sports

Internalized Racism in Sports

“I realize that I am black, but I like to be viewed as a person, and this is everybody’s wish.”

Michael Jordan once spoke these words in an interview when referring to how he wants to be seen by the world. Sports have always been an outlet for performing through which no race should ever interfere. Whether it be on the court, the field, the pool or the track, once an athlete enters their world of competition, the pigment of one’s skin is just a color, not a defining attribute.

But even though sports are defined by wins and losses, social movements have poured into this world, and the platform given to athletes at any level of competition has been used to make statements regarding many issues.

At Cherry Hill High School East, racism may not be the most prevalent, but sports provide a safe place for all that participate. Speaking with athletes who use sports as a way of promoting their views, these men and women remain proud of who they are as people and athletes during a time where unity is necessary.

The Cherry Hill East football team allowed players to have the option of kneeling during the national anthem this year. Senior Nick Tomasselo and junior Kelvin Parris took this opportunity to make their mark, along with coach, Lynell Payne.

“I knelt during the season to make people aware of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement,” Tomasello said. “I don’t want others judging their decisions.”

Tomasello also wanted to support his teammates of minority backgrounds. As a leader, he felt his job was to promote a friendly team atmosphere.

“I wanted to keep them motivated for the next season and to hopefully have a playoff run soon,” Tomasello said. By kneeling along with Parris, Tomasello was able to provide an example of what true leadership looks like— camaraderie in the face of adversity.

Junior Pierce Atkins, on the Cherry Hill East soccer team has a different perspective of social pressure in sports.

“I don’t believe sports are an outlet for social issues because I personally don’t feel overwhelmed by the social issues,” Atkins said.

Atkins still said he does recognize that some student athletes are impacted by their ethnicity, but he does not feel that he can speak out based on his own experiences.

“Being one of the few black kids who play soccer in South Jersey, I still have not experienced any discrimination,” Atkins said.

The same cannot be said for senior Christian Brown, a hurdler for Cherry Hill East’s track and field team. Brown participates in a sport where he is not exactly a minority, but has still dealt with issues.

“There will be many times I’ll hear people talk and say— ‘he’s black, we’re not going to win,’ or something along those lines,” Brown said.

But like Atkins, he too does not believe sports need to be an outlet for social issues.

“In competition, everyone is focused on the one goal and that is to improve their ability,” Brown said. “But I do feel that athletes should be able to speak out against any oppression going on in the world given that we have to spotlight these events.”

Brown has even experienced direct name-calling and derogatory terms being flung his way by competitors and fellow students alike.

Brown said, “since I’ve moved here, I’ve had issues with racism more than once. I notice it because it is directed towards me, even if it is very lowkey.”

Senior Peyton McGregor, a volleyball player at East, has a different perspective as a female minority athlete.

“For me in volleyball there aren’t a lot of racial issues,” McGregor began. “But I have experienced a few comments thrown at me. One time a competitor called my team an ‘Oreo’ because of our diversity. My color does not define me as a person, so after we beat them I did not have a problem talking about it with them and my mom, who is white.”

McGregor goes to tournaments in which she is one of the only African-American players, but remains unbothered. She did say, though, that the parents of other teams see color more than the players.

“The girls are all just competitors, so they don’t view each other as black or white, usually. But the parents do make comments sometimes,” McGregor said.

Sports may take a back seat to social issues, but athletes everywhere have used their position to make their mark on the movement, shining light on issues that we keep in the dark. Even at the high school level, race is a topic that cannot be put on the backburner for any longer, and it takes people like athletes to help advocate for change.

Student Perspectives

Hispanic identity is not defined by the negative stereotype

In this world we are continually being classified by our race and identity, and for some individuals it’s difficult to look past that. Despite the fact that in the past many fought for equality and to stop prejudice and separation, it actually happens.

Many of the Hispanic community have been criticized for speaking Spanish, being seen as alcoholics and criminals, and being told to go back to their homes. Racist groups take advantage of the illegal Latino population. They believe the Latino population have no rights due to their illegal status here in the United States. They certainly know many Hispanics won’t go to the police to report these acts of discriminations due to fear of being deported, so they live in silence. Hispanic employees have really experienced very unfair job mistreatment from their employers both in public and private sectors. Despite their hard work in jobs, no credit or appreciation is accorded to them for instance: wages raise; no chances for ideas sharing since their ideas are considered unworthy towards bringing forth development. I, as a daughter, have seen my parents go through racism hundreds of times because of these situations. I’ve never truly seen them stand up for themselves and not only just my parents, I’ve seen it happen to other people, even on the news.

We Hispanics are hard working people who come to the United States for a better life. Yes, there are Hispanics who are typically viewed as a negative stereotype, but that does not identify all of us.

How I Strive to Impact the Community

I have always been an active member in my community, both in and out of school. However, I changed from just being “a part of my community” to “impacting my community” recently, by stepping out of my comfort zone to bring the community together.

It is important to use this time in our lives to educate ourselves and notice that Black People are still suffering from systematic racism and oppression.

After being inspired by the growing Black Lives Matter movement across the country, the leaders of the African American culture club and I decided to take action as well. Over this past summer, we organized a protest and march called “The Learning Begins Now; Stop the Ignorance” in our community in order to emphasize the importance and necessity of the education of African American history in our school districts, by demanding a mandatory African American Studies course as a graduation requirement. My involvement with the movement has not ended with the conclusion of the protest. I have continued to push for the development of a new African American

Studies course as well as the African American Studies curriculum.

I did not leave it up solely to the district to implement these changes; I have volunteered my time on many occasions to challenge and change the system in place. There was a Social Justice Committee formed where we are working with author, Gholdy Muhammand, to implement in all subjects and grade levels in order to “Cultivate Genius “ in all students, especially those that are systematically marginalized.

There was another committee formed called Courageous Conversations, which are discussions with the Camden County Superintendents as well as other Camden County students regarding reforms in our school communities to benefit underserved students, especially those of minorities. In addition, I have continued to voice my opinions and have been interviewed by the Philadelphia Inquirer. I was also interviewed by Debrah Roberts for an ABC News Nightline story that has not been released yet.

However, the work that needs to be done is not over; as for this is not a trend, it is a movement that people of my generation are changing. So despite leaving for college soon, I will continue to not only use my voice to present solutions for my home community, but take any actions necessary in order to be a part of these solutions.

My views on Anti-Semitisim

Before I proceed with this story, I believe it is significant to mention that this story is merely my interpretation and endurance of Anti-Semitism. In consideration of my approaching revelations, I do not endeavor to make you, the reader, feel as if my story is the only inference of Anti-Semitism. There are, undeniably, contrasting stories of Anti-Semitism that are concealed by Jewish individuals. It is noteworthy to comprehend that the event of my story may not be entirely applicable to those around me nor those around you; however, I do believe that you will find some comparison to your life or to the lives of those around you.

I do not think the events of this story had a distinct beginning nor will they have an immediate conclusion. I truly feel that there is no direct response to what it means to be Jewish. A question as simple as “is Judaism an ethnicity, nationality, faith, culture, or heritage?” among more. I guarantee you that if you asked every Jew on this planet, not every individual will offer you the same response nor reasoning. Although this question does not seem prominent, it has evolved the way I have identified myself as a member of the Jewish community, especially those occasions where someone asked me what Judaism was and I did not have a discrete answer. Honestly, this bothered me. It appeared to me as if I did not have the right to say I was Jewish if I did not know what it meant. I think that with this question in mind, the older I get, and the more I learn about my core beliefs, my response will continue to change. Although this is true, to quote my father, “at the end of the day, [I am still] Jewish.”

I personally have never referred to Judaism as a race, nevertheless, I will say that I have undergone internalized racism. So you might be thinking, “how has she gone through internalized racism if Judaism is not a race?” Internalized racism can be defined in several ways, even so, they all share similar terms. For instance, internalized racism can be defined as “the personal conscious or subconscious acceptance of the dominant society’s racist views, stereotypes and biases of one’s ethnic group and gives rise to patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that result in discriminating, minimizing, criticizing, finding fault, invalidating, and hating oneself while simultaneously valuing the dominant culture.” In spite of the fact that not all of these qualities apply to me, I can confidently say that quite a few of them do.

I find it frustrating when people showcase their thought that they are permitted to address any inexcusable and offensive remark to someone with the reasoning that it is not “racist.” I have encountered a number of individuals who suggest that their First Amendment “immunities” grant them the freedom to say anything of their choice along with the ability to avoid the potential consequences. Here, I believe situates an evident misconception. Yes, anyone can say anything, except should they say everything? I think not.

I have always pondered at the thought that people seemed so interested in my inherited and genetic features compared to every other Jewish student in my school environment, which are, indisputably, beyond my control. Once more, this is a “thought.” It had not crossed my mind that perhaps a Jewish kid passed by me in the secluded hallways of the school and was harassed in regards to their inherited and genetic features. Yet, when this conclusion came to mind, I thought, “maybe they just do not talk about it.” I do not blame them, though. Why would they, though, when so many other students have made such a firm assumption of what it means to be Jewish?

Ever since I was younger, I have received differing comments concerning stereotypical and prejudice criticisms specifically directed towards me, dating back to before and highlighted during the Holocaust. Someone once looked at my nose and asked “why are all Jewish people’s noses so big?” as they pressed their finger against their nose and focused their attention on that of my own. On another occasion, someone was trying to guess my name and before they even estimated they said, “you’re jewish right?” using a tone and glaring at me with a smirk as if it was not even a question but that they have accurately, and made abundantly clear, assumed that I was Jewish. I remember, on both these instances, responding in a confused manner. I narrowed in my vision and stared at their expression, silently questioning them in my mind. What does that even mean—I look Jewish? Is that even a bad thing?

Moreover, the most pronounced of comments always scrutinize my demeanor. As I am sure many high school students can relate to, I am exhausted in the morning after hours of efficiently completing homework all the while having to awaken early the next morning to catch a ride on the bus, and with no disregard, following this schedule the following day. In no way do I feel responsible for having to wear a full face of makeup and dress accordingly. For those of you who are able to do so, I admire that. Be that as it may, when I do have time to put on five minutes worth of makeup, students around me feel it is essential to “inform” me that I am wealthy or self-absorbed (among more that I do not feel are appropriate to mention), neither of which are the case. Please keep in mind that I do not assume this, people will say it to my face if that is what they think. These notions are made after “confirming” that I am Jewish. But why? Not all Jewish people are wealthy and self-absorbed, just like how any other segregated group of people do not consist of the same characteristics. We are all people.

To this day, every time I come home and rant about this to my father, as these events prove to be persistent, who is a born and raised Israeli, he always reminds me that at the end of the day “we are all Jewish” as I mentioned before. When I say this I am referring to the amount of times other Jewish teenagers in and out of my school atmosphere have perceived me as not Jewish because I care about people and endeavor to be nice to those around me, or perhaps because I attend school, in-person or virtually, wearing a hoodie and sweatpants almost every day, while other girls my age like to reveal parts of their body that should be kept for themselves and disobey dress codes. (Before I continue, I would like to reinforce that I choose acceptance over judgement every day and I only mention this because any of these interpretations are just as offensive as the other.) My mind has been brainwashed by the society around me to think that every Jewish girl presents herself like this. I find myself constantly trying to prove myself to others as if I am not the “typical” Jewish girl. This has taken much of my love for my traditional background and beliefs. It is almost like I am ashamed to be Jewish.

Truthfully, I believe that most individuals who try to l0ok like something they are not present this persona and demeanor to everyone around them that they “do not care” what others think. Yes, some people do not care. Do you know why? People who truly do not care what others think of them are those that dress and act the way they want to dress and act. So if this were to happen, it does not matter if you wear less and are confident about the way you look (in appropriate settings). I am not saying that it is inferior to look any specific way. I am all about people dressing and acting to exemplify and express who they are; but not who they are not. This is where the problem lies.

Furthermore, I find it embarrassing sometimes to come from a cultural background that a large number of people, in the past and present, have disapproved of. I have had people try and remind me what I am “supposed to” believe in. Yes, I am Jewish, but I am also my own individual.

I found a dissimilarity that discerns American Jews, European Jews, and Israeli Jews. I cannot assure you, but I doubt, that Israelis will tell you that they do not do, act, or celebrate the same practices as American Jews with European origins. This observation has interfered with my thinking and prompted my shame for being Jewish. I became so confused when I was trying to differentiate what I was. I can now proudly say that I am in between. I am part of the first generation of Americans in my overall family, and I will tell you—my family is ginormous. It humours me when my father is speaking of an extended family member and I have absolutely no idea as to who he is referring to. Continuously, it is difficult to fit into both cultures.

Here, in New Jersey or in the country as a whole, I might pronounce a word “incorrectly,” when really that is how you would enunciate a Hebrew term and it has been “Americanized.” Then, there are times where I am pronouncing a word incorrectly because what I say may be an English word but I have grown accustomed to hearing my parents articulate words with their foreign accents. Every time the holiday season comes around, people ask me what I received for Hanukkah and I respond with “nothing.” They would ask me that for eight days straight and the response alters. Not receiving a gift every single day of the holiday is not upsetting in my family, because we only receive gifts every time we see a different family member, once again, given that my family is ginormous. As I am sure many can relate, Jewish or not, family and extended family are spread all over the country or even across the globe. For me, I barely have any family here except for my intermediate family. I rarely see my extended family who, most of them, live about a twelve hour flight away from here. I understand that it would be disappointing for someone not to be granted a gift every day of the holiday if that is their tradition. As for me, I personally ask for things that cannot be handed to me in a box wrapped in gifting paper. I would prefer to be respected with truth, loyalty, and honesty from the people I care about, and for some reason, those traits are easier to say and harder to give. But to quote my dad for the third time, American Jews, European Jews, Israeli Jews, and anything in between, “at the end of the day, we are all Jewish.”

Something in particular that always irritated me was when both my parents’ Israeli friends or my family from Israel speak to me in English and then say something about me, positive or negative, to my parents or others that are spending time with one another, beside me, at a gathering of some sort. Part of this lay fault on me for not speaking Hebrew to them, although much of that ignorance comes from the fact their children do not understand nor speak Hebrew and therefore, cannot pass down the language to their own future children. It is still somewhat disappointing to feel as if I am not Israeli because I am assumed to not know the language, obviously, though, what is disappointing is not that I do not know Hebrew, as I do, rather as if I am disappointing the Israeli community because I choose not to speak Hebrew in public. It is not because I cannot; it is because just as many people who come from foreign countries to America and have accents, I have a slight American accent when I speak Hebrew. I do not think people notice it as much as I think they do, as it really is not a thick accent, I am just aware of the way I pronounce words in a language so far from English because I feel that there is something wrong with not being able to emphasize a word formally. This is where I feel like a hypocrite.

I will never bystand when most of the Americans who I have come across have commented on both my parents’ accents. The amount of times people just laugh when my parents say something, not because it was funny or necessarily because they find it humorous that they could not pronounce a term, but usually due to the fact that they feel awkward and did not understand what my parents say is quite troubling. They will say to me either “what did they say,” between their grinding teeth as they attempt to hold up a smile or “your parents are so funny.” Yes, they can be, but in a different aspect. We are loud, talkative and opinionated! People take advantage of my parents because they give and do not take. My parents are constantly undermined for their capabilities because they are from a different country. I could never say I have endured this, but I have watched my parents when they are stressed and anxious after they return home from work and lose a position or job to someone who is less educated and determined as them, but they were born and raised within this country and do not have accents. I have had discussions with my mother about how disappointed she is under circumstances such as these, but at the same time she knows how “connections” are crucial. If my parents have accents but they are able to speak two to three more languages than a child raised after generations of American-born citizens, why should I feel ashamed that I am fortunate enough to speak English fluently and understand two other languages in which I do not speak as well? I should not, that is the answer.

I cannot ever say that I am ashamed of my skin color, as I know that although my genetic features are beyond my control, it is almost a privilege to be white in a society where any other race developed as a “minority.” Despite the fact that I might not struggle with the color of my skin, that does not mean that other cultural characteristics are excluded from my shame. For instance, when I am laughing or exercising, not even excessively, my face will turn an abnormal pigment of red. As for my brother, he has come home with people asking him if he is Hispanic or South Asian, when he is Middle Eastern and Eastearn European. Again, why do people say these things as if they are horrible or offensive?

There are various expectations for beauty depending on traditions, culture, and location, among more. Think about it: I know that if I go to a tropical country that receives heat, sunlight, or humidity on the daily basis, even perhaps that of my father’s heritage, I am seen as an outsider, as someone who is assumed not to know the language, have an arrogant personality, as people notice my light, fair, and sun-sensitive skin. On the other hand, if I spend time here, in my hometown area of New Jersey suburbs, I seem American in a less unorthodox way, where people speak English to me because they are in a country where the foremost language is English.

People do not always think my brother and I are related. Candidly, I have one of those faces where countless people tell me I look like someone they have seen recently, a past student, or generally, someone I have never known. My brother has adopted my father’s tan and brown-tinted skin, dark brown almost black hair, and tall height. Me, contrastingly, I do not fall far from the tree to my mother in regards to appearance. My hazel eyes and light-brown hair do not fool anyone—I look like her when she was my age. Anyways, my brother is still my brother and I do not think it is fair for people to make assumptions only to use them as judgement.

Now, I am proud to say that I am a Jew. I am proud to say that throughout the horrific events of oppression and death that Jewish people have endured in the past in which prompt emotions that could never be expressed in the words of the English language, how beautiful it is to know that those who survived passed town a tradition that was lost by many others. I am proud that I am more than a Jew but that I may advocate for myself. I am proud that I was raised to love and embrace all creations of life, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, and more. I am proud that I hold a name that represents my heritage. I can only hope to continue growing and developing as an influential figure, individual, and voice.

After reading this, all I ask is the next time an assumption or judgment crosses your mind, as we are humans and thinking these thoughts come naturally, ask yourself if it would offend anyone if you were to tell them what you were thinking. You might not think that it is offensive, but if a part of you is even debating whether to comment or not, just do not. The more you hold back what you want to say only to give yourself a few moments to reflect on the consequences of your words, you will become more conscious of the reactions people have when someone, other than you, comments on the way they dressed or their features that they have no control over. I guarantee you that the more that individuals do not hear remarks on their appearance, the less they will judge themselves from within. Yes, there will always be the parts of who we are that we see as “imperfections” or “flaws,” but those judgments, if anything, should not come from other people. This will only make the insecurities feel more overwhelming. If people allow themselves to grow out of their insecurities, as others do not comment on their appearance, then they will be more successful in learning to love themselves for their religion, faith, beliefs, culture, ethnicity, passions, traditions, and even the things that they wish they could change about themselves. What is notable is that everyone tries to not judge others and choose acceptance instead, every time you wake up in the morning, throughout the day, and every time you close your eyes to rest. What is not acceptable is when people choose rejection and judgment every day. So try. I promise it is worth it.

Insight on the culture clubs at Cherry Hill East

An in-depth discussion about the multiple culture clubs established at Cherry Hill High School East and their significance.

Many topics are covered such as representation within the school, Multicultural Day, and racism.