From the Spanish Flu to Covid-19 pandemic, past East teacher recalls a century-long life journey

There is some intangible feeling when hearing the stories of the past. The vividness of life which winds people in millions of unforeseeable ways awes us all. These weathered stories have allowed many to glimpse into infinite perspectives of love, loss, and perseverance.

102-year-old Mary Green, who taught Home Economics at East from 1969 to 1984, has done just that–shared her rich experiences and allowed us to peer into a century of life and history.

Born in 1919 in Colorado, Green lost her mother to the Spanish influenza when she was only 11 months old. From then on, her dad and extended family remained a constant force as she grew up.

When Green turned 11, in 1929, the Great Depression hit. Having lost his business and becoming bankrupt, her father left for almost a year to find work.

“The only thing he owned was his car, so he sold it and walked to Maryland to look for a job,” explained Green.

During this period, Green was surrounded by her large family: cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents, which rooted her during a tumultuous time in the country.

“I had a happy childhood…My father had five sisters and four brothers, and they all lived in that area…like one big family…We would gather around the piano and sing and have taffy pulling parties,” recalled Green fondly.

As an avid student, Green discovered her passion for chemistry and English in high school. After graduating as high school salutatorian in 1936, she attended Shepherd University, where she thrived with her fellow classmates and nurtured her love for learning. Amidst the rigorous science-based classes she took, including physics and organic chemistry, her favorite memories were making TNT and aspirin.

It was in college that Green’s interest in home economics piqued. Although she took the course in high school, she didn’t feel she enjoyed it.

“We never did much. We made soup once…and a boy said, ‘That’s the first time I ever ate water with a spoon,’” said Green while chuckling.

As a result, in 1940, at the beginning of her senior year, she transferred to Michigan State University to pursue a degree in Home Economics, a subject specializing in food and resource management, health and nutrition, and sewing and interior design.

After graduating college, Green worked as a home demonstration agent with Potomac Edison, a power company, teaching clients how to use appliances like ovens and stoves.

Among her fondest memories, she recollected cooking for 300-person crowds, and her demonstration of tasty Thanksgiving meals received enthusiastic praise.

At a time when kerosene lamps still lit many homes, she also served as a saleswoman to persuade people to install electrical power in their farms.

“One man particularly wanted to put a radio in his barn to play soft music, because music makes contented cows and contented cows give more milk,” laughed Green.

Green enjoyed her work and seemed like she had found her path in life. Then, an unexpected obstacle hit: World War II.

“When we heard that on the radio, we just couldn’t believe what had happened…It was near Christmas and we were all happy…but not that day. It was like there was a black cloud,” recalled Green.

In light of this, her husband, who had joined the Marine Corps before their marriage, was immediately deployed to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, just three months after their marriage. She decided to move to a one room apartment near the camp to be closer to him.

“We would have meals together on weekends…there wasn’t a whole lot to do,” described Green.

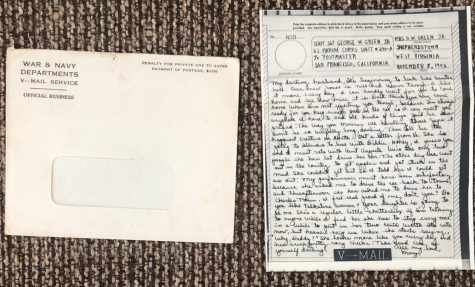

A year later, her husband was transferred overseas to the Pacific, and Green moved back home to West Virginia to live with her father. Their first daughter was born two weeks after he was transferred. She communicated with her husband through Victory mail, the primary postal system created during the war to correspond with soldiers overseas.

“There was just an atmosphere of, ‘we can beat this thing,’” said Green firmly.

It was in this climate that she rationed her food, harvested from her father’s victory garden, and persevered as the nation marched together through the war.

Although her husband was far away, there were happy moments. On Christmas, at the instruction of her husband’s Victory mail, her dad bought a lush bouquet of roses to surprise Green underneath the Christmas tree.

There were also times of perseverance. At some point, she started trading her meat ration stamps for canned food so she could buy baby food for her newborn daughter.

“You do what you have to do. I just adjusted. Wherever I was, I was happy,” explained Green.

It was a time of worry, but their spirit of victory helped shine a light at the end of the tunnel. Finally the war was over, and her husband returned home. He and Green moved to Cherry Hill in 1955.

“I didn’t want to teach. That was something that I told myself,” recollected Green.

Little did she know, she would find herself teaching at East through a spiderweb of events.

To help with college tuition for her three daughters, Green started substituting in the Cherry Hill Public School district in 1966. After five years of being a substitute teacher, Green was offered a home economics teaching position at the newly opened East. She taught basic foods, international foods, natural foods, and four levels of sewing classes in F-Wing.

“I wrote the two courses on International foods and Natural foods,” said Green.

These two new courses varied from cooking healthful foods to cultural foods, including Swedish meatballs and Bratwurst. Among her favorite memories, she taught a student how to cook the best broccoli he had ever eaten, an even better compliment considering he had disliked vegetables so intensely before taking her class.

During her teaching career at East, Green was a dedicated teacher to her students. She would go the extra mile to help just a single student. Having learned that a student with cerebral palsy wanted to sew, she offered to go to the student’s home to teach her so she could give the student her undivided attention.

“I didn’t want to be a teacher at first, but then I loved it,” said Green, “I think I was prepared for teaching all along. My…work as a demonstrator was also a way of teaching.”

Green retired in 1984 after 15 years of teaching at East.

When asked for life advice, she said, “Don’t feel that you have to follow certain patterns…be who you are.”

Green did exactly that. Persevering through the Spanish Flu, Great Depression, and World War II, Green pursued her passion for learning and developed her love for teaching.

From the strength and tranquility in Green’s eyes, one can see a vibrant journey of over a century of remarkable living.

The human spirit overcomes.

Whether Alena is chasing a story or talking to a friend, she asks thought-provoking queries in hopes of sparking meaningful conversations. She finds joy...

Ashley Schwendy • Feb 21, 2022 at 6:15 pm

My great grandma ❤️ such an amazing woman. She will be missed.

barry schifreen '71 • Jan 15, 2022 at 6:43 pm

Her picture from the 1971 yearbook is at this doc: https://tinyURL.com/71faculty-2 , lists of East faculty/staff/administration/coaches, living & deceased, from my era. Scroll to the very bottom of the doc, then scroll up a little bit. Thanks for the article. We’d like to invite her to our 51 year reunion, whenever Covid allows us to select a date! How can I contact her?

Shad • Dec 8, 2021 at 12:21 pm

That’s so cool!