America’s prisons maintain a legacy of cruelty and injustice

When George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man, died on May 25, 2020, after a police officer continued to kneel on his neck, the world stopped. Although this was not the first instance of police brutality to be exacted on a person of color and certainly not the last, Floyd’s death catapulted the Black Lives Matter movement into action. This movement seeks to take a closer look at racial prejudice within the police system and the intrinsic oppression of minority groups existing in prisons. The oppression that marginalized communities face in the prison system is ubiquitous across the United States today and since the dawning of the country.

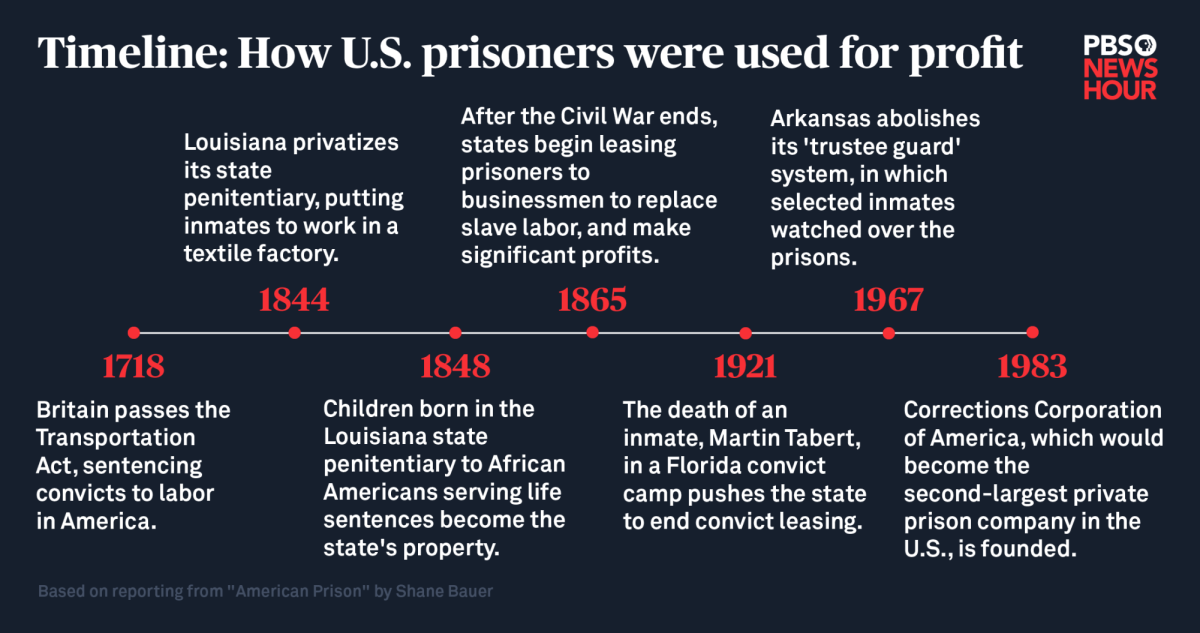

Specifically, African Americans have undoubtedly faced a long-standing history of discrimination in the United States, being policed as early as the 1700s through slave patrols. These patrols aimed to instill fear in enslaved Black individuals, stopping the occurrence of uprisings and reducing the amount of runaways by using excessive force. This form of policing eventually faded as a result of the 13th Amendment, however, it reappeared in the form of militia groups who enforced Black Codes. With the additional implementation of the convict leasing system and chain gangs, African Americans in prison were instructed to complete penal labor in a rebirthed form of slavery. Later in the 20th century, police departments began forcibly imposing Jim Crow laws, upholding the systemic racial disparities in the country.

Since these early forms of policing, the United States has adopted a system of mass incarceration, where the prison population contains nearly 2 million detainees, according to Statistica. The United States is the world leader in its prison population, even surpassing China, which has roughly four times the population. However, the population of prisoners in the country is significantly disproportionate to the population of Americans in society.

Minority groups constitute a large percentage of detainees, significantly larger than their population in the United States. According to the Sentencing Project, Black Americans are imprisoned at approximately five times the rate of white Americans, and one in five African Americans can expect to go to prison sometime during their life. Latinx communities also face this disproportionate representation, being incarcerated at over two times the rate of white Americans. Additionally, the Safety and Justice Challenge said that Black and Latinx individuals make up 51% of the prison population while only constituting 30% of American society. As a result, the majority of African Americans and members of the Latinx community feel targeted in their everyday lives.

The population of prisons is largely at the discretion of police officers, whose prejudice can sometimes play a role in arrests. In some cases, police officers may stop and search vehicles depending on their own racial bias. As stated by the NAACP, African Americans are five times more likely to be stopped without cause compared to white individuals. Furthermore, 45% of Black adults have reported being unfairly pulled over, while only nine percent of white Americans claimed to have been pulled over without cause, according to Partners for Justice. In the case of drug offenses, Black Americans are also four times as likely to be arrested compared to white Americans, oftentimes serving hefty sentences as a result. This disparity in arrests contributes to the inordinate amount of African Americans occupying prisons. Sometimes, police officers can make arrests based on one’s criminal record, further exacerbating the issue for minorities who have previously fallen victim to prejudice in the policing system.

Moreover, when individuals are placed in pre-trial detention after they are arrested, those who cannot afford to pay bail are disadvantaged. This causes a large population of impoverished individuals within the prison system. In fact, those who are economically disadvantaged are 20 times more likely to be incarcerated in their lifetime, according to Partners for Justice. In severe cases, impoverished individuals have to resort to crime to fulfill their basic needs for food and shelter. Since this desperation lands impoverished communities at high risk for incarceration, polling from Partners for Justice suggests that many Americans are in favor of creating policies that satiate the basic needs of the community instead of increasing funding in the police and prison systems.

The disproportionate imprisonment of marginalized groups only exacerbates the racial and economic disparities in society, even after the incarcerated individuals are released. After enduring violence, a lack of sanitation and overcrowding behind bars, formerly imprisoned people typically struggle to get back on their feet. According to the NAACP, there are approximately 50,000 legal restrictions that block previously incarcerated individuals from obtaining jobs, finding housing and gaining access to education, and almost 75% of previously incarcerated people are still unemployed a year after their release. Due to these restrictions, minority groups, especially African Americans and the impoverished, struggle to make a living and find success after imprisonment. The ACLU also acknowledges that while 650,000 people return from prison every year across the country, half of them return to prison within a few years as a ramification of these blockades.

Through mass incarceration and deep-rooted prejudice within the prison system, prison frequently intensifies the imbalance between races and social classes. By first acknowledging the presence of bias and making sure the needs of impoverished individuals are satisfied through preventative policies, society can diminish the chasm between the population of minorities in the prison system and their population in society.

The Atlantic provides an in depth look at mass incarceration in our country.

In addition to discussions regarding the prison system’s discriminatory and inflamed incarceration rates, a look at the prison system’s problematic living conditions is necessary.

America’s prisons are among the worst among developed countries in terms of occurrences of sexual assault, violence and exhortion in the prisoner population. Not only that, but the threat of death itself is ever present in American prisons. For example, in 2020, the UCLA Law Behind Bars Data Project documented over 6,000 deaths among the incarcerated population. This number cannot be chalked off to external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2018, the number hovered above 4,000 – at a rate of 344 out of every 100,000 prisoners dead, according to the Vera Institute. Not only death, but one in ten inmates in prison suffer from sexual violence at the hands of fellow inmates, according to the Nolan Center for Justice. Understaffed and overcrowded prisons, negligent prison officials and staff all result in these conditions being exacerbated rather than alleviated.

Another undeniable factor for these horrific numbers is mental health in America’s prison population. According to Mental Health America, over half of all incarcerated individuals in America possess mental health problems. And yet, a popular method of disciplinary action among prison officials includes solitary confinement. Studies by the National Alliance on Mental Illness found that solitary confinement both perpetuated previous mental instabilities in individuals as well as led to the formation of new psychiatric conditions. Even more problematic are solitary confinement’s effects on prisoners after release – it has been proven that released inmates are more likely to commit suicide if they were subjected to solitary confinement while in prison.

These are only some of the issues that exist in our prison system. In the end, 6 out of 7 of America’s prisoners will return to society. Whether we want rehabilitated, healthy individuals in our public life or traumatized, damaged and dangerous individuals is a decision solely in the hands of the federal and state governments in our country.

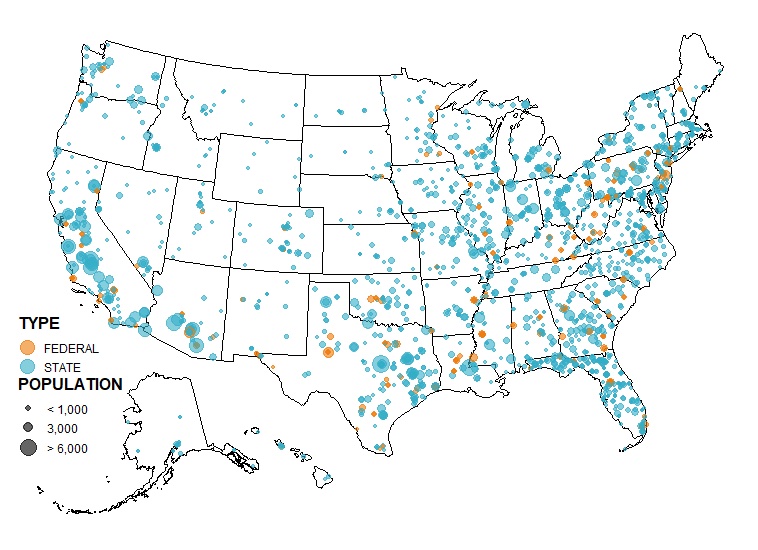

A map from a Colorado State University study (fueled by a NASA grant) to research environmental justice across the prison system highlights the spread of over 1,800 prisons across the United States, bringing to light the heavy presence such institutions have in our country.

In the United States there are two types of prisons: public and private. Public prisons are owned by the government, and usually operated by the government. On the other hand, private prisons are contacted by the government, meaning that 3rd party organizations oversee them. Another difference between them is by nature, private prisons are run for a profit, while public state and federally run private prisons are not. This means that prisoners in private prisons, about 8% of the prison population according to The Sentencing project in 2021, are there to generate revenue.

There is a reason why Private Prisons are so popular in the United States. In a country that imprisons the most citizens in the world, there are many prisoners and not necessarily enough space to fit them all. As a result, private prisons are often used to offset some of this overcrowding. In addition, it also saves the government money because they don’t have to operate prisons, which cost a significant amount to maintain.

This profit-driven mindset affects the experience of prisoners in these private prisons. In the 27 states that utilize private prisons both prisoners and prison staff are less safe than their counterparts in government-run prisons. In 2016 the former deputy attorney general, Sally Yates, said private prisons “simply do not provide the same level of correctional services, programs, and resources; they do not save substantially on costs; and … they do not maintain the same level of safety and security.” This is evidenced by the fact that, According to the US Department of Justice, violent attacks by inmates on correctional staff were found to be 163% higher in private facilities. Partially for these reasons, Gitnux Market Data reported that “The rate of staff turnover in private prisons is 53% higher than in their public counterparts.” Further highlighting this point is that staff in private prisons earn less and receive less training than their counterparts in public prisons, according to the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. Similar to the staff, prisoners in private prisons are also put at a higher risk. According to the same study by the US Department of Justice, inmate violence against each other was 30% higher in private prisons than in public prisons.

Because of the fact that private prisons are often run less well than government ones, some politicians have aimed to have them banned. During the Obama administration Sally Yates, as mentioned before, attempted to reduce and eventually phase out private prisons under the guise that they were not an adequate substitute for government facilities. However Jeff Session, the attorney general during the Trump Administration, wrote that with this order the Obama administration had “changed long-standing policy and practice, and impaired the bureau’s ability to meet the future needs of the federal correctional system,” arguing that the private prisons were necessary to prevent overcrowding. As recently as 2021, the Biden administration ordered that no federal contracts with private prisons be renewed, which in theory should eventually end US’s dependence on private prisons.

There are some flaws in this plan to get rid of private prisons. The first is that this is only under the jurisdiction of the federal government, and won’t get rid of the many state prisons. The other issue is that this isn’t a permanent solution, as another administration could easily reverse this decision in a similar way to the previous time this was proposed. The only permanent way to shut down these unsafe and inadequate institutions is by a law passed by congress. For the most positive effect, this should happen sooner rather than later.

The individual walks slowly down the hallway to the small room they have been expecting for what has likely been a decade or more. They are directed into a small room with a table in the center. They lie down before being constrained by straps. On one wall, a one-way mirror guards a room containing affected family members and journalists. Finally, someone prepares equipment for what seems to be an almost alien attempt at mimicking a standard medical procedure. But this is not a standard checkup; it is the cold, methodical process for executing prisoners used by over two dozen states throughout the nation.

Throughout history, almost all civilizations have used executions as a means for both punishing and preventing transgressions against society. The idea of capital punishment as a deterrent for criminal activity led many societies to adopt gruesome and disturbingly public means of ending life. Burnings at the stake, drawings and quarterings, crucifixions, and hangings displayed victims enduring excruciating pain before their bodies would be left on display for all passerby to see. These events displayed the cruel power of the state to take life in an unflinching manner before massive crowds you were either willing or forced to watch.

The crimes throughout history that carried this heavy toll varied, with many facing death for minor offenses such as heresy, theft, and arson. Additionally, the evidence required for such offenses was extremely low, with many innocent lives facing capital punishment. In more recent centuries, most countries began to shift to reserving capital punishment for more severe offenses such as murder, piracy, and treason. Governments also started to move away from the more torturous styles of execution, with the adoption of the standard drop hanging that killed via the breaking of necks rather than strangulation, firing squads, and decapitations. Though still very visceral and gruesome sights, these methods drastically reduced the amount of pain felt by the condemned individual. Additionally, some scholars began to question the true effectiveness of capital punishment in deterring crime, leading many areas to move executions to more private areas.

With the development of the electric chair in the 1880s, the United States entered a period of scientific exploration into how executions could become more humane. The prevalence of botched hangings caused outcry among many, leading some to embrace the concept of the electric chair as revolutionary and a great step forward ethically. However, the electric chair also carried extreme pain. The sensation of the electric shocks has been compared to that of being burned alive until all ability to sense pain is lost. A number of botched executions in which people had to endure multiple rounds of electric shocks before death also highlighted the cruelty of the method.

Up until the late 1970s, electric chairs (and gas chambers to a lesser extent) served as the two main forms of execution in the United States. The closed doors nature of these methods and scientific connotation made the public feel that these methods were humane, despite the severe pain associated with both. With the proposition of a three drug method created by Oklahoma’s state medical examiner Dr. Jay Chapman, many thought that the most humane method of execution had been developed.

The most common form of lethal injection utilizes a combination of three types of drugs. First, a fast-acting barbiturate is injected as an anesthetic to reduce pain and movement. Then, a muscle relaxant is used to induce paralysis of the muscles in the body. Finally, a potassium salt is injected to cause the heart to stop. After each drug has been injected, a saline solution is pumped through the veins to hasten the process by which the drugs take effect.

Many opponents to lethal injection take issue with the specific drugs used in the process. For one, the type of barbiturates used in the process do not have long-lasting effects for pain reduction. This means that an individual subject to lethal injection may feel extreme pain during their execution, but they would have no way of signaling that pain due to the paralytic state caused by the muscle relaxant. Additionally, some have cast doubt on Chapman’s strategy in choosing the drugs for his method, claiming that he was not an expert in the specific effects of each substance. Shortages of the drugs originally outlined by Chapman have also led many states to substitute in other drugs for the process, heightening the risk of botched executions. Rather than truly create a less painful process, some argue that lethal injection merely presents the image of a less cruel death.

A key issue with the practice of lethal injection comes into play when considering who delivers the injections. Because medical practitioners have taken an oath to do no harm, only non-medical professionals can perform lethal injections. This means individuals who are not experts in medicine perform the executions, increasing risk of incorrect dosages and botches. This lack of experience is highlighted by a situation in Ohio from 2009, where an execution team could not locate a vein to use for the injection despite full cooperation from the condemned man and around two hours of searching. Additionally, the botch rate of lethal injections has been calculated to be the highest of any modern method. Austin Sarat, a professor at Amherst College, calculated the botch rate of lethal injections to be around an astonishing 7.12% compared to 1.92% for electrocution.

Finally, the implementation of capital punishment in the first place has extremely problematic connotations. Death prevents an inmate from any chance at being exonerated in cases of wrongful conviction. University of Michigan professor Samuel Gross estimated that around 4% of individuals on death row have been innocent. A fraction of these individual’s lives could have been saved if they had instead been sentenced to life in prison, where new technology or case revisits could allow them to achieve freedom. Additionally, there appears to be a strong racial factor in determining what punishment a convict receives. Black and Hispanic individuals are overrepresented on death row, and white convicts and victims seem to attract more sympathy during sentencing. Finally, it is less expensive to keep a convict on death row for life than it is to execute a convict due to the long appeals processes and the cost of drugs used in lethal injections.

Due to all the procedural and ethical concerns with the implementation of the death penalty, one solution seems obvious: abolishing the death penalty. This move seems to be growing in popularity across the United States, with 23 states having abolished the use of the death penalty and six states where governors have ordered a moratorium on executions. For centuries, we have attempted to develop a process for ethically ending someone’s life. However, the truth remains that there will never be a perfect way of executing someone because of the countless issues like determining guilt, standardizing implementation of executions, and accounting for prejudice in society.