The Mandela Effect: How could something you seem so positive about be wrong?

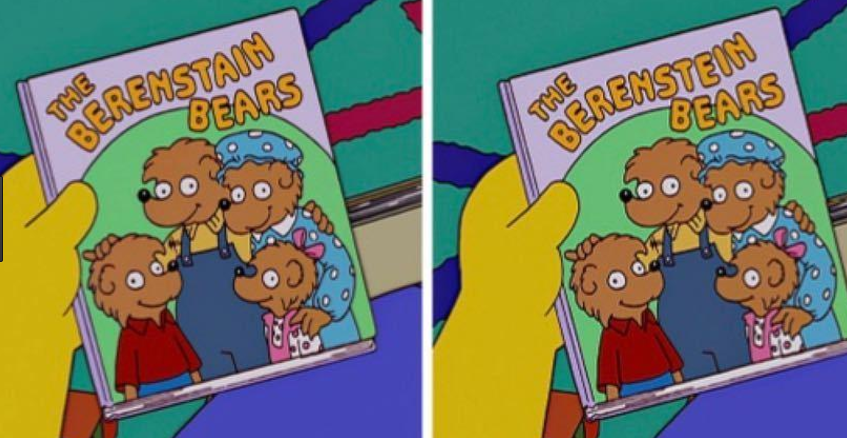

Which one is it? Do you remember?

The human brain has been mystifying researchers ever since it was first studied in the fifteenth century. The brain is known to have many odd quirks–especially in relation to memory. Memories are often twisted, changed and developed in different parts of the brain, and when they are recalled, it is from those fragments. This makes it simple to discredit the unconventional memories of one individual, or even a small groups of people. However, when large groups of people “collectively misremember” a certain event or thing, researchers are left scratching their heads once again. This instance of “collective misremembering” is known as the Mandela Effect.

The Mandela Effect has woven itself into popular culture through songs, children’s novels and even classic movies. One of the most famous movie quotes of all time can be found in Star Wars V: The Empire Strikes Back, when Darth Vader says, “Luke, I am your father” to the young Jedi. Right?

Well, not really. It turns out that Vader says, “No, I am your father.” But how could such an iconic line be so misquoted? Some say the Mandela Effect is to blame.

The “Mandela Effect” is a term coined by Fiona Broome, to describe when a person has a clear memory of an event that never historically happened. It is named the Mandela Effect due to a popular piece of evidence documented by followers of this phenomenon. Broome states that she, among “thousands of people” remember Nelson Mandela, world leader and peace advocator, dying in prison in the mid-1980s. This is clearly not true, as he died in December of 2013.

While there are many theories about why this happens, ranging from ideas of parallel universes with alternate timelines to alien abductions, there is no complete consensus as to why people remember certain events occurring that never actually happened.

Many are skeptical that the Mandela Effect even exists. Some attribute the phenomenon to the “misinformation effect,” which is when the recalling of an event is less accurate due to information given after the incident occurs. Skeptics also cite confirmation bias. This is when people search for, favor and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses for odd events that support the Mandela Effect.

Another piece of support cited by believers of the effect can be found in the Berenstein vs. Berenstain debate. Internet platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, and Reddit have been abuzz with commenters who specifically remember the children’s book series, “The Berenstain Bears” being called “The Berenstein Bears.”

In “Snow White”, the witch never says “mirror mirror on the wall”. Instead, she said “magic mirror on the wall.”

The Mandela Effect even extends to peanut butter companies. Some swear that they’ve used the brand “Jiffy”, but a peanut butter company named Jiffy does not exist. This example, however, could just be due to confusion between companies “Skippy” and “Jif.” This does not make it any less unsettling for those who believe in the effect.

“It’s really weird because it’s like you remember something one way and then you hear that the way you remember something being your whole life is actually different,” said Lori Pacuku (‘19), who did not believe in the Mandela Effect until she heard that the Berenstain Bears series was never spelled with an “e” after the “t”.

The causes of this bizarre effect can be hotly debated, but there’s no denying that it is a fascinating look into the way the brain perceives information. Followers of the Mandela Effect are certainly not stopping in their search for the truth behind these instances of “collective misremembering.”