Amidst the various topics explored on the popular online newsletter The Marginalian–philosophy, science, art, history, psychology, and more–one stands out as unexpected: children’s books. At first glance, it may seem out of place. What could picture books and fairy tales do with discussions of such weighty subjects?

The assumption is familiar–children’s fiction is often viewed as not being as important, difficult to write, or profound as literature for adults. But in truth, children’s books are not lesser, nor are they meant solely for children. As C.S. Lewis once said: “A children’s story that can only be enjoyed by children is not a good children’s story in the slightest.”

Even after we believe we’ve outgrown the colorful illustrations and oversized fonts, children’s books stay with us. They might sit on the highest shelves, tucked away behind heavier books, or find a new home in the hands of another child. We treat them as artifacts of our childhood, gradually forgetting how they once shaped the way we saw the world. We assume their lessons are too straightforward and too obvious.

But great children’s books are anything but simple. They are distilled philosophies, illuminating what growing up often obscures, helping us return to what we used to know but have since unconsciously learned to set aside. They ask questions that, while simple, can strip away the complexities that expand as we age–all expressed in the language of children. Questions about friendship, the meaning of life, loss, and love are not only present in children’s literature; they are approached with a sincerity and uninhibited curiosity that can be lost with time.

Julie Paschkis’s “The Wordy Book” captures this beautifully, asking questions that seem playful yet carry weight: “What lies beyond beyond? When does the end turn into a beginning? When does then become now? How will I know?” These questions encourage us to confront the boundaries of what we can comprehend, embracing the wonder and curiosity that wanes as we age.

In the book “Why You Should Read Children’s Books, Even Though You Are So Old And Wise”, author Katherine Rundell delves deeper into this idea, arguing that the best children’s fiction “helps us refind things we may not even know we have lost.” These books transport us back to when “new discoveries came daily and when the world was colossal, before the imagination was trimmed and neatened.” Children’s literature can remind us of the expansive, untamed way we used to see the world before the constraints of age or experience took hold.

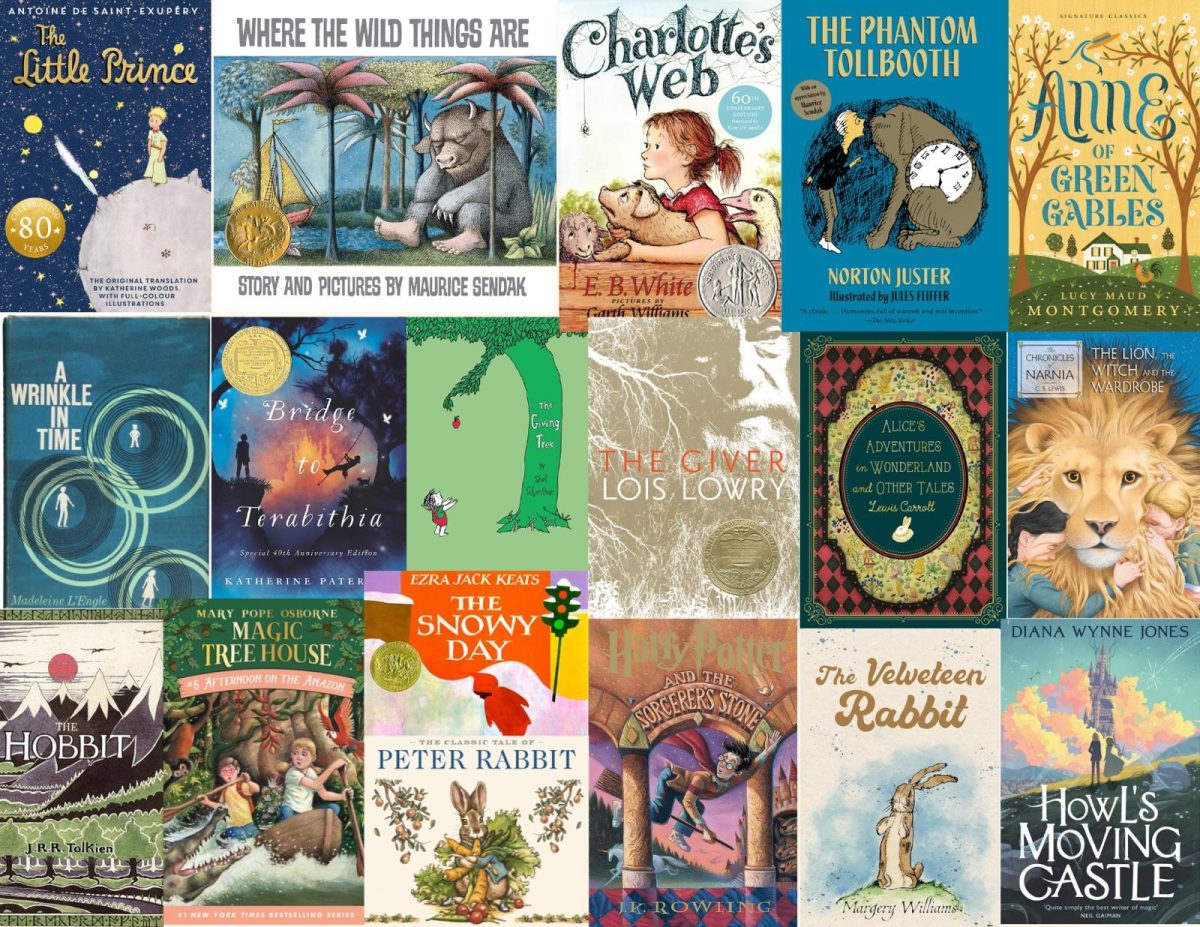

As we go through life, our once vivid imagination, instinctive empathy, and unselfconscious sense of morality can waver. However, books like “Bridge to Terabithia” and “The Phantom Tollbooth” can reignite our imaginations again, urging us to explore worlds beyond ours that we haven’t visited since childhood and expanding our sense of possibility. “Charlotte’s Web” teaches us compassion through touching acts of friendship and kindness, while “The Hundred Dresses” reminds us of the painful consequences of being complicit for acceptance.

Adults and teenagers may turn these pages and say, “It’s not that simple,” dismissing timeless truths. But, in that very dismissal, we forget that the simplicity is the depth. The absolute and undisputable clarity of these lessons, pure of complexity and cynicism, is exactly what makes them so profound.

We are never too old for children’s books. They should continue to be read and reread even as we grow, not solely because they are nostalgic, but because their lessons are eternal. They remind us that the empathy, bravery, imagination, and wonder we had as children were never meant to be left behind.