Lynell Payne’s Plan

Cherry Hill East assistant football coach Lynell Payne kneels next to senior Nick Tomasselo before a game against Paul VI.

Lead by example. Do your part. Know what matters.

Every high school athlete dreams of the moments where they can perform in front of a crowd, load the stat sheet, earn the accolades, and break the records. Lynell Payne was no different.

Growing up in Marlton, New Jersey, Payne considered himself a “hooper” during his upbringing. Dangerously athletic, Payne was a scoring threat from all over the court, and although he admits the fundamentals weren’t always sound, he was able to excel with pure god-given ability.

Payne would attend Cherokee High School as a two-sport athlete, participating in basketball and track & field. It wasn’t just participation though, it was domination. He was fairly tall at 6’3, and weighed around 200 pounds by the end of his junior year, a build that could be viewed as limited on the court. Either way, Payne knew he was good, his opponents knew he was good, and everybody watching could tell you the same.

And as humble as he is, Payne won’t shy away from letting you know, either.

“I was a beast, man. I knew that they had to stop me, so I never really had to prepare much,” said Payne.

So when a friend came up to him with an opportunity for a new challenge, Payne was not about to back down.

“My buddy said ‘might as well come out and play football,’ so I did,” said Payne. A simple decision that would not only change Payne’s future, but his view of the world.

Know what matters.

To Payne, football would turn out to be more than just a game, it became a lifestyle. The workouts and training sessions were intense, and he knew that if he was in peak physical condition, his future would write itself.

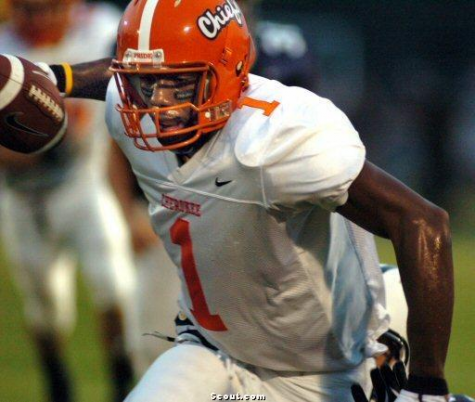

Payne played on a diverse Cherokee team that had championship aspirations each and every year. Wearing No. 1, he was a varsity starter his sophomore, junior and senior seasons. He still remembers his teammates and the high school community, but specific moments stick out to Payne more than everything.

Lynell Payne played receiver and defensive back for the Cherokee Chiefs. (Scout.com).

“Thanksgiving game my junior year,” said Payne. “We played our crosstown rivals Seneca at our home turf…” and he trails off.

The other end of the phone turns quiet as he reminisces about the game. Then I hear a crackle on the other line.

“I’m a black man at the end of the day,” Payne says. That’s it. It takes several more minutes for the story of that day to come out. And it is easy to see why Payne takes a deep breath before telling it.

The year was 2006. Payne played wide receiver and defensive back on a team that had already clinched a championship berth for the season. The Thanksgiving showdowns were always fun for the fans, and that day the Cherokee Chiefs’ stadium was packed. Payne’s team was already looking ahead to the next week’s matchup against Absegami, so he knew that the starters would only be playing for two quarters.

And those two quarters remain clear in his mind to this day.

“I got tackled only 3 or 4 times that game,” Payne said. “But each time I was tackled, Seneca’s players would hit me with racial slurs until the next play.”

“Wait, what?” I ask in awe.

Payne had said that he never “really” experienced racism in his life. And here he was telling me that curse words and slurs were being flung his way in one of the biggest games of the season.

“It was just a culture shock. They were the only school, only players to ever do that,” Payne said.

Picture a young Payne catching the ball, turning up the field and getting tackled at the knees by two white players. As he shuffles to get to his feet, the opponents are spitting at him, stepping on his cleats, and calling him names that he has never been called before.

“That’s when I realized that sports are more than just a game,” said Payne.

In the game of football, where jersey colors, names and numbers are all that should be seen, Payne was on the receiving end of minor insults that his people have been hearing for centuries. Social issues were brought to the field for Payne that day, and he hasn’t shut the memory out.

“I was not a victim that day. It was just another game for me,” said Payne, who noted that when he is on the field, he is too zoned in to comprehend moments like this fully.

Payne knew that Seneca players would return to their bubble after the game, a bubble where race was an afterthought because it was a predominantly white school. He knew that football had just become another part of his life in which the color of his skin mattered to some. And he also knew that at the next level, it would be the people within the program that helped make his decision, not any fame or clout.

Do your part.

Payne was a 3-star recruit coming out of Cherokee and received over 20 offers from Division 1 programs such as UConn, Temple and Maryland before eventually deciding on Cincinnati. Cincinnati’s head coach at the time was Brian Kelly (who is now the head coach at Notre Dame), who was initially the reason Payne wanted to attend the school.

“Coach Kelly was bringing in the best class in the nation,” said Payne. “I wanted to be a part of what they had going.”

Payne’s recruiting class to Cincinnati included future NFL talent’s Travis Kelce and Isaiah Pead, but his freshman year went a lot differently than he anticipated.

Payne red-shirted during the 2009 season, taking a practice role and extending his four-years of eligibility. During this year, he says that the game became more about studying film and learning the game than actually playing.

“I became a student of football,” Payne said. “It made me a better player and a harder worker.”

But just like in his high school career, his years at Cincinnati provided many more memories that have helped shape Payne’s character today.

“I remember walking down the hallway and coach Brian Kelly would walk right past me,” Payne said. “I probably had around 2 conversations with him in 3 years. College football is a business, they care about what you could do for them.”

Under Brian Kelly, the 2009-2010 Cincinnati team would rally together with an “us against the world” mentality that rocketed them to an undefeated regular season. They would face off against Florida in the Sugar Bowl after being shut out of the BCS championship game by a 1-loss Texas team.

“Coach Kelly cared about the wins. He was a great coach with tactics, but the players really had to rely on each other,” Payne said.

This was evident when days before the Sugar Bowl, Kelly would take the job at Notre Dame and leave his team without their head coach in the biggest game of the year. Offensive Coordinator Jeff Quinn (who had taken the head coaching job at Buffalo but chose to stay for the bowl game) became the interim coach.

Needless to say, Cincinnati’s undefeated season came to an end at the hands of Tim Tebow’s record-breaking performance in which he threw for 482 yards and scored 4 total touchdowns. The game itself is not what Payne remembers, though, it is the circumstances that surrounded it.

“I knew that we had the best offense in the country with Kelly,” Payne said. “But I also knew that it was up to the players in the end, and there was a slight disconnect between us and the coaches.”

After two more years at Cincinnati, Payne would transfer to Youngstown State before a 4-year stint in the Arena Football League. His studying as a redshirt freshman had given him a new appreciation for the game, but through this process he learned that character goes much further than the X’s and O’s.

“After experiencing different coaching styles as a player, I knew that if I went into coaching it’d be to bridge the gap between players and their coaches,” Payne said.

Today, Payne is the varsity assistant coach at Cherry Hill High School East and the varsity basketball coach at Woodbury High School.

His story does not end there, though.

Payne’s career as a player gave him all the tools necessary to succeed as a player’s coach instead of a normal coach.

Let me explain.

At Cincinnati, Payne saw firsthand how certain players were neglected by the higher-ups in the coaching staff, and he knew this prevented any development not only on the field, but off of it.

“I want to be the same person outside of a coaching setting as I am in it. All I want is to make my players better, and that means I need to show them I care,” said Payne.

His goal as a coach is to not only teach his players the game, but teach them life skills they can use outside of football.

“It’s all about the balance between being a ‘Cool Uncle’ vs. being an ‘Angry Stepdad,’ because athletes need both,” Payne said with a laugh. “But since my players know that I am invested in them, they respond to what I say.”

Lead by example.

Payne uses his voice through football to motivate and translate messages to his players. But he has also created bonds with them that go beyond the game, implementing his coaching mentality and providing a positive influence on those around him.

“If I can act the same way every day, the consistency will one day rub off on the people who watch me,” said Payne.

And this year it did.

As a football coach during the 2020 fall season, Lynell Payne decided to kneel before each game. As a reporter I saw this week in and week out, the consistency that is needed to produce a message powerful enough to make an impact.

“I knelt because I understand that I am a black man at the end of the day. If there are any eyes on me when I make my mark, I know that there’s a chance a conversation can come from it,” Payne said.

“Whether it be in the car after the game or at a dinner table that night, if I can have one person say ‘did you see that man kneeling today,’ I know I am making a small impact,” he said.

The “Black Lives Matter” movement felt personal to Payne, and he knew that he could have a role in creating a productive dialogue at the end of the day. Like a coach to a player, Payne could help educate those who were unaware of his message and use his position for good.

When asked why he knelt and why sports are important for social issues, he responded bluntly.

“Sports are the perfect platform because they are a huge part of U.S. culture,” he said.

And he is very right. People tune in to sports as a form of entertainment, an escape from the realities seen in the news. So if ESPN is promoting social issues, or if players are making social statements, the public needs to hear them in order to watch the sports they love.

“I don’t watch the news,” said Payne. “All it is is death and destruction every day. Sports are the platform that we need to advance as a society.”

“Without Colin Kaepernick or the NBA, we are left with no channels to talk about social causes,” he continued. “Entertainers can only go so far as puppets, athletes can keep it real with eyes on them.”

There it was again. The eyes. A movement is not a movement without people tuning in, and Payne knows that in order to keep attention on this issue, it’ll take people like him to use their platforms.

“I just want to start by becoming a good human being. Being a good person is a mentality…If I can become a good human being, I can start to help other people become the same,” he said.

Payne has a young daughter that he instills these virtues upon. He wants her to be aware of what is going on and always judge people by their character.

“If we can all talk to, treat and respect one another, we can advance,” Payne said. “If I can be real with myself, I can then move on to other people.”

He ended the conversation with this- “A friend is a friend.”

When I asked him what it meant, he told me that it takes viewing others beyond their race to truly understand them.

Know what matters. Do your part. Lead by example.

Lynell Payne is not defined by his race, and neither is anybody else. Everybody has an outlet or a platform through which they can spread a message, and Payne’s was football.

He helped lead a few protests over the last couple of months, but his biggest impact comes in the form of everyday actions- having an open dialogue with players, understanding them, and teaching them how to be the best people off the field that they can be.

“If I can make a little impact I can go to sleep knowing that I am doing my part,” said Payne.

With the eyes of spectators at his back, Payne knows that they can see him on one knee, staring at the American flag. But what they can’t see are the experiences that have brought him to where he is today. And as a black man in America, Payne is proud of knowing that he is part of a complex story for change.

“The country is still trying to figure it out. But I know that this is all for a bigger cause.”