Dance is a sport

Dance has been around for centuries, a practice where students learn styles ranging from ballet to hip-hop from ages as early as three up to their adult lives. But behind the glittering performances and sparkling tutus on stage, the dance world is one full of discipline, pressure over body image, and confusion over the proper role of a dance teacher in a class setting.

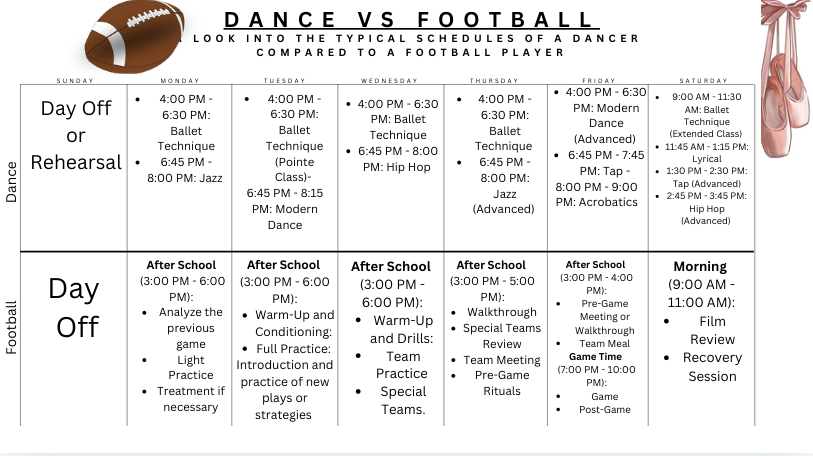

The study of dance, similar to that of a sport, is not something you can learn overnight. Dance is a fusion of movement, music, and emotional artistry, requiring immense training and perseverance to succeed. Many students begin this training as young as three years old, dedicating themselves to the studio for hours both after school and on weekends to refine their technique and better themselves as well-rounded dancers. Training often begins very basic with young children, with the level of difficulty gradually increasing as the children get older and prepare to dance at a professional level.

The role of a dance teacher is often misunderstood in the dance world, balancing a relationship between correcting their dancers and still maintaining positive relationships with their students. Teachers strive to instill discipline and creativity in their dancers, but their strictness can be equally demanding at times. For ballet in particular, high standards and strict expectations are the norm, often creating immense pressure and expectations that can lead to stress and burnout.

One of the biggest challenges a dancer faces throughout their dance career is the pressure of their body image. Dance as a whole, often emphasizes the aesthetic of every single dancer, and a dancer’s body type can often influence their opportunities and casting. The idealized image of a dancer is typically represented by a slim, flexible, and strong individual, leaving those who do not fit this ideal feeling as if they are not good enough. However, many dance companies have become aware of these issues and demands of the “stereotypical dancer body” and are actively working to promote a healthier body image and more inclusive representations of dancers across the industry.

Between basketballs, baseballs, footballs and hockey pucks, many Americans are under the impression that in order to be a real sport, some object has to be thrown, aimed or passed. While this narrow definition rings true for many quintessential sports, sports generally encompass any activity involving physical effort and competition. Many sports involve copious training, requiring a certain level of skill to become proficient. This vague definition leaves room for an age-old question: Is dance a sport?

Most individuals categorize dance as a performing art, using movement as a vehicle for expression and storytelling. Using creativity and imagination to craft routines and choreography, dance can communicate powerful messages while entertaining large audiences. Unlike traditional sports, dance involves subjectivity as a piece of guiding music can have limitless interpretations. Each step of choreography often has purpose, similar to the intention embedded in each brush stroke on a canvas or each note in a musical arrangement. In addition to the movement itself, many dance pieces involve emotions and facial expressions to create another layer of meaning, just as sound devices and diction can add new meaning to literature. With such purposeful physical expression and storytelling, most individuals believe dance is unequivocally an art form.

While dance does certainly align with the arts, this limited perspective can discount the immense skill and practice that go into dance. Most dancers train rigorously throughout the week, prepping their bodies to move in an expansive range of motion and flexibility. Dance also requires great stamina as an anaerobic activity, consisting of intense but short exertions of energy at a time. Similar to many traditional sports, dance can entail teamwork and partnership to reach a common goal or tell one cohesive story. Individuals and teams can even compete dances, fulfilling the standard sport definition.

Sammy Zweben (‘01), lifelong dancer and Co-Creator of Cherry Hill dance studio ZZ Dance, believes dance can be both a sport and an art.

“I think if people don’t wanna say [dance is a] sport, it’s because they don’t really know how much energy and strength it takes to do it. While it’s athletic, it’s also an art to me because it is one of the most beautiful ways to express your body. While you do have to do things correctly, you can have more freedom,” she said.

However, unlike most sports, she believes dance offers something entirely unique: the chance to perform.

“I tried every sport, [but] I was just hyper fixated on dance … I just really liked being on stage. There’s a high that I still get performing on stage that I can’t replicate in any other way. I just love being in front of an audience.”

Zweben also acknowledged that in each style of dance, there’s a varying amount of freedom to make artistic choices. While some styles are centered around uniformity, others allow more room for creative expression.

“I think that dance teams in college are absolutely without a doubt one hundred percent only a sport. In fact, when I went to college, I felt like all the artistry was actually stripped from me and I was not allowed to be myself, which is hard for me because like I said earlier, I love to be on stage to perform, and I didn’t like to look like everybody else,” she said.

Since dance places a heavy emphasis on balance, flexibility and coordination, many athletes even use dance to improve in their own sport. Many football players, for example, take ballet lessons to gain strength and become more agile on the field, avoiding injuries. Generally, skills learned in dance can easily translate into other athletic disciplines.

“I’ve watched the football team at my college warm up, and we do exactly the same exercises, getting your heart rate going and then cooling down. [We both stretched] doing pikes, bridges, straddles, leg stretches and lunges,” Zweben said. “When I did karate, I was really good right away because there were forms that you had to follow, and they basically felt like choreography to me. I was able to get to the next belt quickly because I could execute them well.”

By acting as both an athletic and artistic outlet, dancers routinely exercise both their minds and bodies. Keeping individuals in shape and also fostering creativity and expression, dance is an undoubtedly rewarding, stimulating extracurricular, straddling the line between sport and art.

“[Dance is] great for your heart, it’s great for your muscles and it’s great for your organs because you’re getting all the oxygen to them. I think that it keeps you limber, especially into your older age. And then mentally, I can’t say enough. When a person that has a bad day walks into [ZZ Dance], if they let go and just focus on the dance, it transforms their energy, really. It really can help people get out of their own way and see that there’s beauty in the day and beauty in the movement,” Zweben said.

On Saturday, October 5th, six varsity football players from Cherry Hill High School East took a dance class. They attended the class at Marcia Hyland Dance & Arts Center, taught by Julia Skoufalos and Jean Skoufalos, with supervision from Gerry Barney. The class was one hour long and was composed of two sections; one with typical ballet warm-ups and one with hip-hop choreography to “One Dance” by Drake. (Choreography by Julia and Jean Skoufalos)

Players in attendance:

- Isaiah Donaldson (’25)

- Tymir Gayle (’26)

- Cole Haddock (’26)

- Dillon Haddock (’27)

- Sean Jamison (’25)

- Denzel Lee (’25)

Dance is a culture of resilience. Whenever an inkling of pain arises, every dancer has the mantra “the show must go on,” drilled into their heads. Whether a toenail gets ripped off, an ankle aches for weeks, or in more dramatic cases, as described on “Dance Moms,” “a… hand [gets] severed by a set coming down,” nobody can miss a beat. Dance is meant to appear effortless; thus, perpetually masking, or even ignoring pain to keep the show running is common practice.

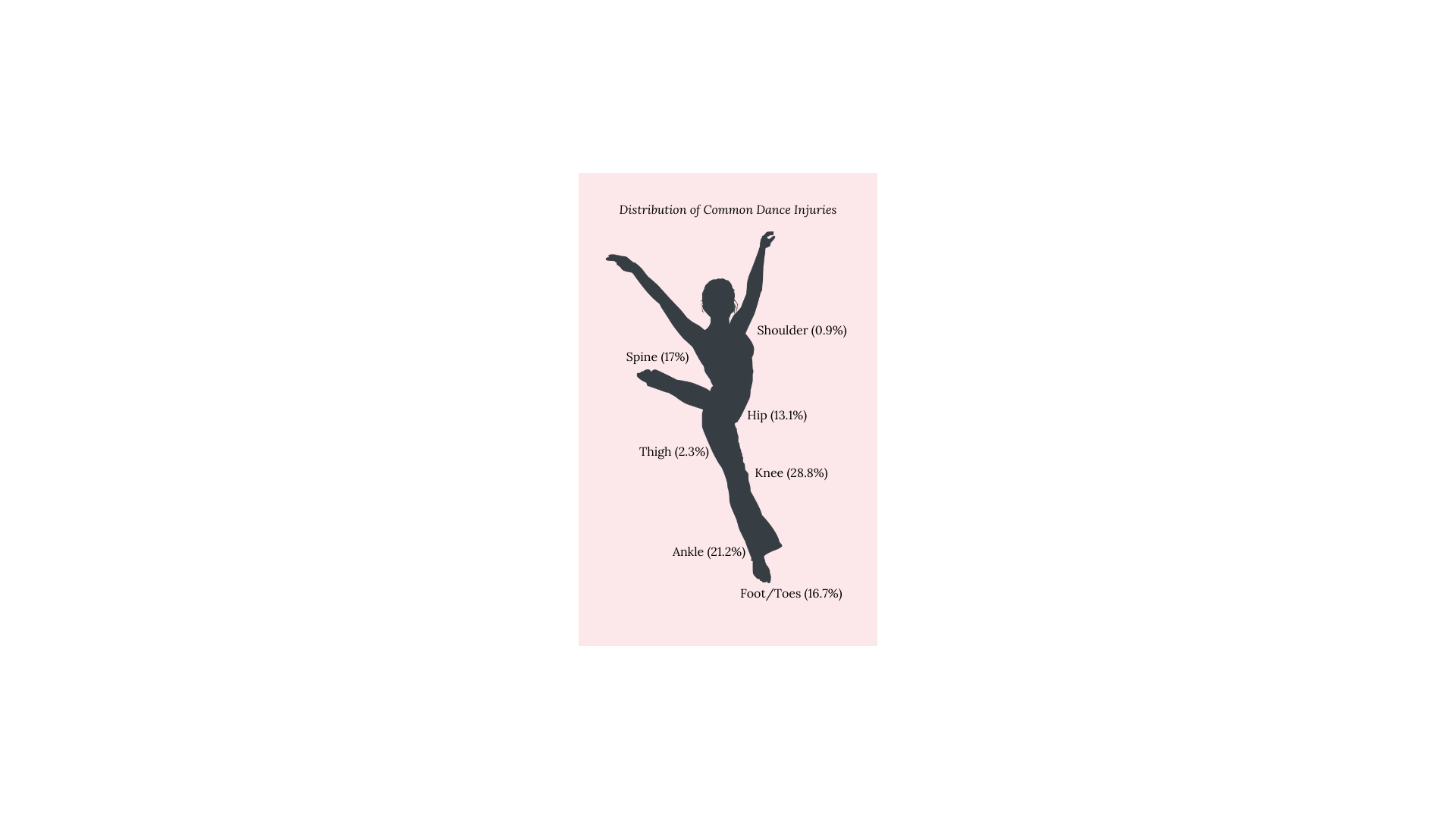

According to the Yale School of Medicine, 97% of dancers experience injuries in a given year. The lines between soreness and lingering injury often blur, with stress fractures, the development of arthritis, and joint dysfunction manifesting from months to years of neglect and continued strain. Young bodies are particularly susceptible to long-lasting injury as the lack of an “off-season” lends itself to little time for recovery and the overuse of certain muscles through the constant repetition of drills to maintain technical brilliance. And as the body can only withstand the ceaseless flexion of and strain on muscles and bones for so long, it is not uncommon for a professional dancer’s career to end before the age of 30.

The demands of a dancer are diametrically contradictory. As an aesthetic-based sport, they must be muscular, yet not too muscular to sacrifice thinness; strong, yet not too strong to overpower flexibility; powerful, yet graceful and delicate. Testing the limits of the human body’s range of motion, the most basic pieces of technique – such as the turn out of the hips – irreversibly alters the anatomy of a young dancer. And on top of long-term strain, finding athletes with hip impingements, stress fractures, hamstring injuries and ankle sprains, or just in a cyclical injury cycle, would not be difficult.

The point of dance is to make everything look effortless. We see pastel costumes and tiaras, perfect makeup and satin shoes. Yet, there are bruises behind ribbons and blood under the tutus. It takes an incredible amount of resilience, strength, and most of all – effort – to make it all look effortless.

Nate Aguelo is a junior at Cherry Hill High School East. He is a male dancer outside of school as well as a volleyball player at East. In this Q&A he will discuss his personal experiences in the dance world as well as his numerous opinions regarding dance.

(This interview has been edited for readability)

Q: How long have you been dancing?

A: 11 years.

Q: What studio do you dance at?

A: Studio 33.

Q: What styles of dance do you takes classes for?

A: I started off with hip-hop. Then, I wanted to try jazz and musical theatre. But I ultimately decided to stick with hip-hop.

Q: As a male dancer, how does your gender play a role in the sport?

A: There are going to be some people judging you at first. Then some people will start to be impressed. When I was in middle school, I listed dance as one of my sports for an “all about me” assignment, because I am very passionate about it. Some kids thought I was gay. I didn’t really know how to feel because I had never been told that before. And I would ask them why they thought I was gay and they would say it is because I am a dancer. It was very interesting because I had never really thought about it at the time. Now I understand that maybe it is a “girl sport,” even though I feel like all genders can participate in the sport.

Q: How many male dancers are at your studio?

A: I am one of three. At competitions, I do not see many other male dancers. The most I have ever seen at one studio has been about five.

Q: How did you get involved in dance?

A: When my mom was looking for studios, around 2013, all of them would either not allow me to take classes there or try to get me to start with ballet. I told my mom that I strictly wanted to do hip-hop. One studio finally let me in and let me take hip-hop classes and I just started from there.

Q: Do you think dance is sport?

A: I see a lot of people saying dance is an art form and that is why it is not considered a sport. I understand that because dance is a form of art. However, it is also a sport. There are some studios that compete with one another, whether it is as a team or individuals under different categories. I think every sport can be seen as a form of art. Dance is a form of art because they express themselves through their movements with the song. They are working their hardest to make the choreography look clean to get a higher score from the judges. For example, if you see volleyball, tennis, or basketball, they have to try their hardest to score after a long period of time or each round. Seeing them working hard and putting their blood, sweat, and tears into their sport, I think that is art in itself. Trying.

Misogyny is defined as a “dislike of, contempt for, or ingrained prejudice against women.” Misogyny is meant to make women feel as if they “owe” something to men or have to earn the right to simply exist. Proclaiming that women are forever less than. To meet these demands, women have felt the need to put on a show and perform for centuries. This can be seen through appearance, productivity, but most of all, dance. Dance was practically made for the male gaze. Something for them to dole over. However, when women decided to make dance something of their own, a way to express themselves, people have struggled to view them as athletes. As dance is female-dominant, does misogyny play a role in the opinion of those who do not consider dance a sport? Despite the culture of dance in the past, the cookie-cutter frames and women made to look identical, it is a new world. Although it is an art, made for others to view, the stamina and endurance it requires, makes it a sport. Let’s face it- the times have changed, and we must change with it.

When I was twelve, my childhood dance teacher told my mom to stop feeding me – that I’d be a better athlete if my body still looked the way it did in a photo she had hung on the wall – a photo in which I was eight, three inches shorter and pre-pubescent. I remember her telling me my stomach looked disgusting in the cropped costume that year; I remember her cupping my thigh in her palms and comparing the circumference to my sister’s leg; and I remember, for the first time, learning and believing that being bigger meant my dancing looked “disgusting.”

My teachers spent their adolescent years in Chinese dance schools. There, it was protocol for girls to be weighed every morning upon entering the building; if they had gained even a fraction of a kilogram, they would be sent to another room to exercise until they could be weighed again and see the number go down. As a dancer, they said, there’s a different standard. You can’t look like the “average” person because dancing is meant to test limits; it’s meant to display the body as abnormally, extraordinarily beautiful. Being skinny means you can jump higher, your lines look cleaner and you won’t have extra “meat” to distract from your movement. This is what they were taught as children, what they held onto for years. And when you care so deeply about pleasing your instructor, the one who judges the value of your abilities within a discipline you work so hard in, it’s only natural that you believe them.

I love dancing. Of the multitude of hobbies I’ve picked up and thrown out the window – from painting to music and volleyball – it’s been the only true, all-encompassing constant. As an art, it’s one of the most freeing forms of expression and release, and as a sport, it’s taught me so much about discipline and given me the most rewarding experiences of my life. But though I appreciate competitive dance, the environment surrounding it has also manifested a ceaseless awareness of my appearance. Spending a decade staring at myself in a mirror-enclosed room – where the point of the sport is essentially to “look the best” performing the movements – fostered a difficult relationship with what I see in front of me.

Between sixth and eighth grade, I grew three inches and looked noticeably thinner upon returning to the studio after quarantine. Only then did I have people tell me I “looked like a dancer.” Even now, the culture surrounding the “dancer’s body” still lives and seeps into the next generation. Through nearly eight-hour-long rehearsals, I see twelve-year-olds at my studio proud that they can get through the day barely eating anything, and excited that, during the most critical stage of development of their lives, they can lose weight rapidly.

The nature of dance itself as an aesthetic-based discipline will always perpetuate some degree of self-awareness if not debilitating self-consciousness. In mainstream media, though, I’m happy to see our definition of the “dancer’s body” widen to encompass different kinds of people and value strength over fragility. I see hope in teaching our young dancers to appreciate their bodies for allowing them to dance, rather than pick them apart for what they look like doing it.