Why do we sleep?

Biologically, it is because sleep is necessary to our health and survival. Sleeping replenishes our brain glycogen levels, thus preserving our energy and allowing us to be conscious and recharged the next day. It regulates circadian rhythms, which control vital functions like digestion, body temperature, and hormone production. Without sleep, our bodies cannot form or maintain the neural pathways necessary for learning, creating new memories, concentrating on our daily lives or responding to stimuli. We sleep because we need to.

But why do we sleep? As teenagers, what is it that motivates us to sleep – or to avoid it?

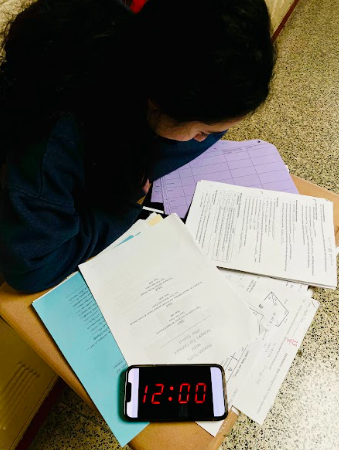

At the end of a long day, jam-packed with activities and homework, we sleep to rest for another long day. It’s an endless, often mundane cycle of school, activities, homework and sleep.

This is where a phenomenon known as reverse bedtime procrastination comes in. Though the origin of this term is uncertain, the earliest written reference appeared in a November 2018 blog post. The post’s author, a man from Guangdong province, described how during the workday he “belonged to someone else” and could only “find himself” once he returned home and could finally lie down.

In essence, reverse bedtime procrastination is the habit of staying up late not because we don’t want to sleep, but because it feels like the only time we truly have control over. For high schoolers – whose days are dictated by repetitive, demanding schedules – those late-night hours become a refuge. Even though we’re exhausted, we scroll on our phones, binge shows, or chat with friends, craving a sense of control over time that otherwise doesn’t feel like ours. It’s ironic, all things considered: in reclaiming our time, we sacrifice the rest we need to get through the next day.

“I love my late nights,” said a student at Cherry Hill High School East who wished to remain anonymous. “I know I’m not supposed to stay up, but it’s the only time I get to feel in control. When I stay up late, I’m not just some robot going to school and work over and over every day.”

Our brains crave downtime to decompress after stressful days. They seek moments of pleasure to counterbalance the chaos – but this need for relief often drives us to choose short-term gratification, like binge-watching or endlessly scrolling, over the longer-term benefits of proper rest. For teens, this trade-off feels worth it in the moment; but it creates a cycle of exhaustion that’s often hard to break.

But where does it end? At what numbers must we stop blaming the students who stay up late, and start blaming a system that innately destroys students’ feelings of control over their time?

A recent survey of Cherry Hill students revealed that approximately 39% of students get below four hours of sleep a night on weekdays, and 80% of those students credited their lack of sleep to binge scrolling on their phones or computers. When asked about weekends, that number rose to about 60%. That’s less than half of the recommended – though highly unrealistic – 8-10 hours a night for teenagers.

Although high school students may resent limiting their time to relax, reducing sleep is likely not the best ‘retaliation’. Sleep deprivation can be detrimental to both physical and mental health, and can have severe long-term consequences. According to author and neuroscientist Mark Walker, insufficient sleep shortens human longevity.

“I know procrastinating my sleep is bad for me,” said Gulmira Yesilyurt (‘25) when asked about her sleep schedule. “But in the moment, I never really care.”

The same survey revealed that over 95% of students who stayed up binge watching videos on their phones or computers knew their routine was unhealthy, but stayed up anyway.

Breaking the cycle of reverse bedtime procrastination requires more than just better habits – it demands a cultural shift in how we view student life. Overloading schedules with endless activities, advanced coursework, and family obligations has become the norm, leaving teens with little control over their time. Instead of normalizing this constant hustle, schools, families, and communities need to prioritize balance.

Creating space for downtime during the day, reducing pressure to fill every moment with productivity, and valuing rest as an essential part of success can help un-normalize the exhaustion teens face.

In the end, true change starts when we stop seeing overloaded schedules as a badge of honor and recognize the value of well-being in the long term.