When dealing with the IDF, cooperation is key

August 25, 2013

You must understand, I am not what you would typically call “bad” and I have, for the most part, avoided getting into any significant domestic or civil trouble. I am actually pretty good, if I dare pay a compliment to myself. I mean I have never been arrested or even grounded for that matter. I have only received detention once – and I managed to wiggle my way out with some verbal coercion and a naïve smile. But, notwithstanding my squeaky-clean goodness, earlier this summer I found myself being heavy-handedly escorted to a room in an poorly-lit Israeli army base by a gruff police officer. With his hand increasingly tightening around my shoulder and his knee rudely hitting the back of my leg, I racked my mind trying to rationalize how this happened. It was pretty uncanny.

Returning to Israel this summer for a three week vacation I did expect some tumultuous exchanges with the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) but I never expected it to escalate to the extent which it did.

Before moving back to the suburban clutches of Cherry Hill, I lived in Israel for seven years and obtained citizenship. Right before returning back to America, like all other seventeen-year-old Israeli citizens, I began the induction process into the IDF. This process is known as Tzav Rishon in Hebrew, roughly translating into “first-notice.”

It is a pretty straight forward deal. You receive a letter in the mail from the IDF detailing where and when to show up. You then, subsequently, get on a bus or make your parents drive you to the listed army base and you spend a tedious day running from one room to the next getting mentally, physically, and psychologically tested. Males, also receive that infamous physical from the ancient Russian doctor who miraculously speaks neither English nor Hebrew. At the end of the oh-so-fun day you receive a score and the IDF places you in a position accordingly. Easy enough? Well, not exactly.

My Tzav Rishon was slightly complicated due to the fact that it took more than a day to complete. This happens a lot and it should have been a non-issue. The IDF simply sends out another letter informing you when to return to the army base. But, for me, it was a great, gargantuan issue because I had left the country before my letter even arrived. That was a big no-no.

By the time I returned to Israel this June, about a year after departing, the IDF along with the State of Israel had issued four warrants for my arrest. I was a brazen outlaw, having unintentionally fled the country over international borders, evading arrest. Do fear me.

Against the vehement advice of my parents, I returned to Israel hoping to rectify the situation. I planned to explain to the IDF it was all a big misunderstanding. We would then laugh and go out for ice cream afterwards. Okay, maybe not the ice cream part. But, I really was determined to settle this problem in a cool, calm, and collected manner. And that is exactly what I did, at first.

I landed at the Ben Gurion International Airport and got through passport control after three long phone calls and a stern lecture from the haggard IDF representative. The guy explained to me he could take me to jail in an instant, but he decided not to. I think it had something to do with the fact that it was 3a.m. in the morning and my arrest would require heaps and heaps of paperwork.

I was free – for the time being. All I had to do was go back to the army base and finish my testing I had started a year earlier, like I promised to the IDF representative at the airport.

Everything was going a little too smoothly for Israeli standards. I did not have to cut through any of the usual red tape and I was only yelled at once. I was cautiously optimistic.

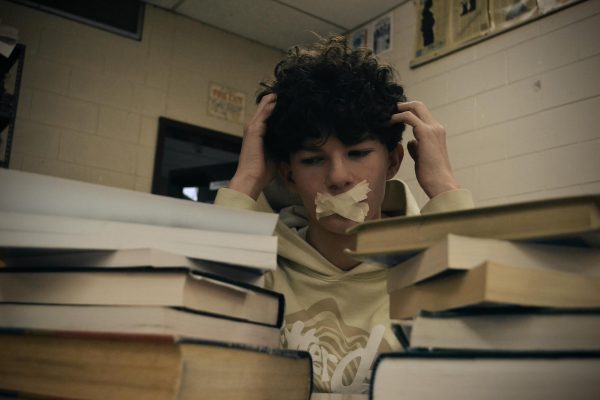

In a matter of days, I returned to the army base and informed the eighteen-year-old, brunette soldier painting her nails at the information desk I was here to finish the testing. Maybe it was the fumes from the nail polish but she haphazardly looked up at me and insisted I have to start all of the testing over again. Sliding my paper work onto the desk, I insisted that she was mistaken and that I was here to simply complete the last part of the testing. She stopped painting her nails, looked at me, and told me rashly in Hebrew, “Don’t argue, it won’t get you anywhere.”

I kindly took her advice and did not argue. I spent the following five hours going from one room to another in the decrepit Tel-Aviv army base retaking all of the tests and redoing all of the psychological interviews. By the time I got to the waiting area for the Russian doctor I sat down and reflected.

I was actually having quite a good time. I met a plethora of Israelis that lived in the area I was staying at and I met quite a few foreigners – from Russia, the UK, and the United States – who were all there volunteering their service to the IDF. I snagged a few invitations to various summer parties and gatherings on the beach and I invited some of the foreigners to hang out with friends. I missed Israel and I was soaking up the open atmosphere.

Having finished the inexorably confusing physical with the Russian doctor I moved on to the final step of the process – the aptitude test. It should have been the most rudimentary, breezy aspect of the entire day. But, things went a little haywire.

I walked up to the desk, smiled, and slid my ID under the glass and awaited a computer assignment. The young soldier, after examining the American surname on my ID, looked up at me and said in staunch Hebrew, “English or Hebrew?” I looked at her and said, “I would like to take the test in English, please.” She proceeded to click away at her computer and said, “No,” without even looking up. “It is too late for the English test, there is nothing I can do.”

I calmly explained to her that I am entitled to an English test and I will not jeopardize my score by taking the test in a second-language. She inhaled deeply, moved her jaw from side to side, and exclaimed, “You are taking that test in Hebrew.”

In retort, I said, “Actually, no I am not going to take the test in Hebrew.”

It was, by that time, five in the afternoon and she wanted nothing more than to go home for the day. She looked to a fellow soldier to her side and said in Hebrew, “Deal with this, I have a bus to catch.” Those two soldiers proceeded to argue and I took a seat.

A few moments later the second soldier came around the desk and approached me. She said, struggling to find the right words, “Eh, listen, you have to take the test in Hebrew you have not a choice.” Looking up and down she continued, “We don’t even have the English test, eh, available.”

I refused with an, admittedly, immature conviction and we argued back and forth. I may have used some choice language and the growing group of soldiers around me began to let their tempers flare and they yelled in unison.

One female soldier, fed up, exclaimed in Hebrew, “Do you know how important this test is?” She let that resonate for a few seconds before continuing, “It will decide where you will spend the next three years of your life.”

“Three years,” she repeated.

I looked back at her and said with reckless disregard, “Exactly, if I mess up this test on account of a language barrier I will end up behind a desk for three straight years just like you.”

Ironically, that sentence came spewing out of my mouth in perfect Hebrew.

In retrospect, as true as that statement was, it was not the smartest thing to say. But, after six hours at the base I no longer had any intact verbal filter.

Thereafter, things escalated very quickly. The soldiers I offended called a police officer on account of my “insubordination” and “threatening language.” The police officer, without mumbling a single word, tapped his handcuffs, and kindly “escorted” me to the testing room with a tenacious grip on my shoulder.

Once we got to the room the unnamed police officer extended a few kind words, “Just shut up and take the test.”

And that I did.

Cooperation is key.