Radical activists earned their part in Black history

Featured in Eastside 2020 issue

Since 1976, people across the United States have celebrated Black History Month in February. This is seen as a time to celebrate the culture and accomplishments of African Americans. Each year, people like Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK) are recognized for their contributions to American society, predominantly for their efforts to combat systemic oppression. As a sign of appreciation, the country has erected national monuments for some, like MLK’s in Washington, D.C. There has even been talk of immortalizing Harriet Tubman on the 20-dollar bill. Largely forgotten, however, are other African Americans who were no less committed to racial equality. Even during Black History Month, this group will receive far less praise. These are the “radicals” of African American history.

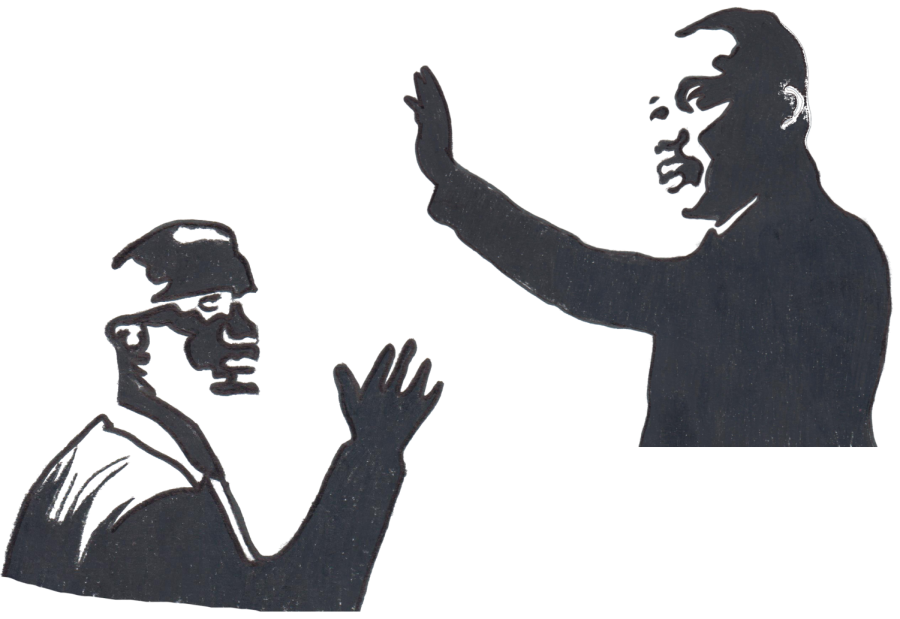

Beyond their race, the celebrated African-American heroes upon whom we heap praise share a common trait. Each, in their quest for equal rights for African Amercans, sought to do so without dismantling the very foundations upon which America was formed. MLK dreamed of an America that would treat his people as equals but never proposed that African Americans would be better off in a country of their own. Harriet Tubman helped slaves escape their bondage while leaving the institution of slavery intact. Both sought changes in degree rather than kind, seeking not to dismantle but to improve. As reflected in the reverence with which these African American reformers are viewed, our country’s history looks most favorably upon those who sought incremental, gradual and incomplete change. Less remembered are those who soughtmore radical change.

Some African American leaders are less remembered. Instead of seeking to change what they viewed as an inherently oppressive system, these leaders endeavored to dismantle it. While Harriet Tubman worked to free slaves, Nathaniel Turner led slaves to take up arms against their masters. While Martin Luther King, Jr. preached sermons about demonstrating compassion and forgiveness for white oppressors , Malcom X argued for equal rights for African Americans (“by any means necessary”).

American history self-servingly de-emphasizes or otherwise sanitizes those who maintained more extreme, or “radical,” ideas about African American equality. Frederick Douglass, a former slave and counselor to Abraham Lincolm, is often thought of as merely an abolitionist. Few realize, however, the extent to which Douglass was willing to fight for African American emancipation. In a speech delivered in 1857, he alluded to the potential necessity of a war and that the country’s sins would be atoned for in blood. People like Malcolm X, Frederick Douglass and Nat Turner are often portrayed as on the periphery rather than the center of American history.

Some might argue that African American leaders are more often recognized or celebrated simply because they were more successful in accomplishing their goals. After all, Martin Luther King, Jr., is remembered for his role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Few could argue that this was indeed some measure of success. But given the profound economic disparities that still exist between African Americans and their white countrymen, one is left to wonder to what extent MLK’s accomplishments can be termed success at all. Further, the role proponents of radical change play in fostering change is often underestimated. Without polarizing characters like Malcolm X, would King’s push for equal rights have been nearly as effective?

Often, when a system is asked to either make significant changes or marginal changes, it typically chooses the latter. Thus, when the United States government and its citizens who were committed to white supremacy were left to choose between MLK’s “civil rights” versus Malcolm X’s “Ballot or the Bullet,” the former seemed the more palatable option. The radical message served as a necessary juxtaposition to the moderate one.

It can be a complicated thing who we revere or consider our heroes. History often tells us that it is only the people who leave the system intact who are worthy of our reverence and remembrance. But there are others, no less committed to change, that are equally worthy.

Harry Green is a senior and second-year Eastside Opinion Editor. He can typically be found in F-087, where he is either creating thought-provoking story...

Iman • Mar 4, 2020 at 9:13 am

This is an excellent article!