Local journalism in N.J. is dying, and N.J.’s fix leaves much to be desired

Last Sunday, Phil Murphy, our governor, signed away 5 million dollars to the creation of a public news consortium, a move which has divided the minimal amount of people who actually have heard about it.

So, let’s start with the basics: the 5 million dollars is not going to be directly in the hands of the government, it will instead be given to representatives of some of New Jersey’s universities, namely Montclair University, the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, and Rowan University.

But why does local journalism need the funding? It’s no state secret that the journalism industry is, in a word, suffering. Print sales are down, advertising revenue is down, readership is down, etc. Online news helps buttress some of these deficits in major newspapers like the New York Times, but ultimately, this doesn’t hold true for more local newspapers (quiz time: when was the last time any of us checked out the online site for the Cherry Hill Sun?). N.J. lawmakers hope to bridge some budget gaps in local newspapers so that robust, local journalism can be accessible to New Jerseyans everywhere.

Great plan! Great plan! Why are people opposed to this, then? I’m glad you asked, o-hypothetical reader. The major opposition to this plan comes under two major umbrellas, both of which were laid out in a POLITICO article earlier this week. One is that journalism needs to hold government accountable and simply isn’t able to do that when government is subsidizing it (think of it as revealing to your company that your boss is laundering money; it’s a great service, but you’re going to get fired). The second reason is connected to the first: corruption. It is everywhere in New Jersey, and it has been since…well, pretty much ever. Observers will rightfully point out that there is not all that much stopping corruption from seeping into the consortium, despite it being (somewhat) privately controlled, as the votes for further funding come from N.J. politicians that naturally want more money for their constituencies programs, and four of thirteen appointees to the consortium’s board come straight from the desks of some of the top legislative officials in the state (five more come from the presidents of the above universities and the remaining four from a majority vote of those nine representatives). Though, the consortium’s proceedings and reports will all be available for public perusal, which may calm some doubts as to its legitimacy; overall, it remains to be seen.

However, both the plan to open the consortium and its opponents miss one crucial detail: this isn’t the whole solution to a sizable problem. Local journalism droughts don’t start and end with fund-choked newsrooms, there is an even more alarming lack of newsrooms. While the grant hopes to amplify the voices of minority and poor communities by helping startups, the grim fact of the matter is that there aren’t nearly enough startups (or funds to fund both startups and longstanding but struggling news entities).

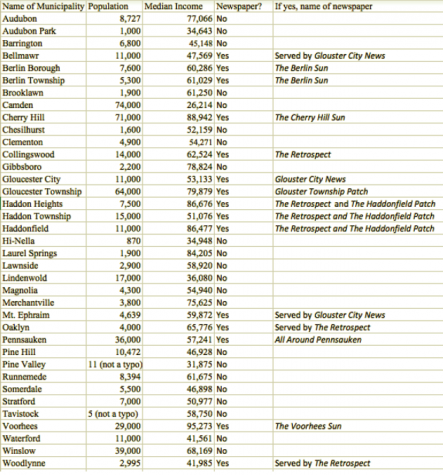

That was quite the word block, so let’s unpack that a bit, shall we? Our local newspaper, The Cherry Hill Sun, has a staff of two reporters and a biweekly, free-to-the-public publication that while ad-heavy, still disseminates some high-quality stuff. We’re lucky to have the Sun, because we are in the minority of Camden County municipalities. Of 37 incorporated municipalities in the county, just 15 are served by local newspapers. Yet, the more startling statistic is that of those 15, just four are served by newspapers that cover no other municipality but their own, of which Cherry Hill is one.

By using Camden County as a microcosm for the whole state, it can be plainly seen that New Jersey’s efforts here may be misplaced. There is only about a $10,000 discrepancy in average median household income between municipalities served by newspapers and those that are not, so perhaps income discrepancy isn’t the problem. Population isn’t a problem either; the lowest population number served by a newspaper in Camden County is just under 3,000 in Woodlynne, whereas the lowest number not served (after Pine Valley and Tavistock’s collective 16 residents) is Audubon Park’s 1,000, just 2,000 people lower. The problem is a giant drought of local journalism entities, which really can only be fixed by showing citizens in communities that there is a civic value in local journalism, something subsidizing existing local journalism programs simply won’t do.

Aine Pierre is now in her fourth year as an Eastside contributor and her 17th year of nerd-dom. When she’s not in F087 debating the opinion editors,...