Students share experiences with substance use disorders

She was only a rising sophomore when she was first exposed to drugs. She only used them once in a while. Maybe every couple of weeks. She felt free. Happy. Like she was having fun. But that was all in the beginning.

Julia’s Story

When former Cherry Hill High School East student Julia Harris’s* sophomore year started, she began getting depressed. And weed became the solution.

If I [was] high, I wasn’t crying. And if I was sober, I was crying.

— Julia Harris

“If I [was] high, I wasn’t crying. And if I was sober, I was crying,” she said.

At East, to educate students about substance use, there are alcohol, vaping, tobacco, and prescription drugs units taught in ninth grade Health classes. In eleventh grade Health classes, a pharmacist comes in to speak to students about substances and elaborates on information taught in freshman year. Ms. Kristen Hildebrand, a Health and Physical Education teacher at East, also incorporates lessons for students to learn about the side effects of substance use disorders, and about where to get help, in a research project that she assigns in her ninth grade classes.

“[The teachers] talked about drugs, and they talked about how it would affect you… [But] it [needs to go] deeper in the situation. They didn’t really talk about [how] a lot of people start using substances because it helps them cope with… past trauma and past abuse,” Harris said.

They didn’t really talk about [how] a lot of people start using substances because it helps them cope with… past trauma and past abuse.

— Julia Harris

Harris was an athlete for her entire life, but that didn’t matter anymore. Field hockey. Lacrosse. Basketball. She quit.

Her friends started distancing themselves from her, and the people who she thought would always care about her didn’t care about her anymore. She became lonely, and soon weed was the only thing that made her feel okay.

“Everybody just judges people’s front and what they put on the outside. You don’t get to know them, you don’t get to know their situation, and you just judge them off [of] what you see,” she said, concerning the stigma around people struggling with substance use disorders at East.

In February of her sophomore year, everything changed. She was statutorily raped.

“That night, I called my friends, and I was trying to find someone to be there for me, and it just got blown off… The fact that they didn’t really understand… It really hurt… I pushed it down completely,” she said.

Nobody understood her. When nobody around her accepted her, she accepted drugs. She was smoking every day. 24/7. From the time she woke up to the time she went to bed.

Mrs. Jennifer DiStefano, East’s Student Assistance Counselor, noted that if a student is struggling, they can come to her through self-referrals, or referrals from friends, family members, teachers, or administrators. After establishing the degree of the student’s use, DiStefano will make recommendations for help, and based on the use and the frequency of their use, she will see that student for support. Then, she tries to get parental support if parents are not aware, and recommends outside support, either through an individual therapist, or, if more help is needed, an intensive outpatient program.

But Harris barely knew her counselors at East; she didn’t even know their names. She said she only remembers meeting with them once for the two years that she attended East. When her mom tried to reach out to them to try to find a therapist for Julia, she could not get the information that she wanted.

“East could not give her any information, and I feel like that’s a high school… they should have that information to be able to give to parents,” Harris said.

When her parents did find her a Substance Abuse interventionist in NJ, she told them, “I’m fine now.” But she wasn’t. She wanted to start over.

Harris transferred to a new school for her junior year of high school and was excited for a fresh chance to make new friends and enter a new environment. But, after finding it difficult to make friends after transferring, she found herself going to the bathroom alone so she could turn to substances.

“I never learned any coping mechanisms. The only coping mechanism I had was to get high.”

Harris numbed everything. She tried to make it all stop. Smoke. School. Smoke. Sleep. But then one time, she smoked and drank at the same time.

Her mom’s brother died while drunk driving and he also killed someone else, so it was instilled in her never to drive while under the influence. But, in November of 2021, she passed out while driving home.

My dad and dog were actually in the car with me when I was driving… It could have been so bad… Something was watching over me and my family that night and gave me another chance.

— Julia Harris

“My dad and dog were actually in the car with me when I was driving. And when I crashed, I almost killed my dad. I almost killed my dog. I could have killed anybody else on the road. It could have been so bad… Something was watching over me and my family that night and gave me another chance.”

The next day, she went to the hospital, and the day after, she was sent to rehab for almost two months.

“In rehab, you have to sit with yourself and sit with your emotions. And understand how you feel… It’s really an emotional process. You are crying a lot; you are trying to understand yourself… But it felt really good to finally [get] my emotions out and not just have to push it down… I feel a lot better now finally being able to talk to people… about how I feel,” she said.

While it did not come to East during 2020 and 2021 as a result of the pandemic, the Jewish Family Children and Services (JFCS) of Southern New Jersey’s program, One Step at a Time (formerly Right In Our Backyard), came between 2017 and 2019 to present their substance use awareness, education, and prevention workshop which has educated 7,000 individuals around the community. Students heard the perspectives of a clinician who specializes in addiction, a member of law enforcement from the Cherry Hill Police Department, an individual in recovery, and two parents who lost their children to accidental overdose. It looks forward to returning to East in the future.

The program was designed to be a complement to the education that students are receiving in schools about substances and to provide another perspective. With the aim to save lives and to normalize the conversation around mental health and substance use, it also tries to give students something impactful to remember— something that can make them stop and think: are these the choices I want to be making?

“What the program in the current form adds to [health education in schools] is not just the …definitions… Our approach has a lot of realism to it… it has a lot of reality… There is an understanding that this is what kids in high school are experiencing and what they are seeing. And then we try as best we can to give corresponding real world solutions, real world tools, real world help, and resources… and to give people hope that there is a way out and there is a way to heal. There is support for everybody,” said Cheryl Herzfeld, who works on outreach and development of the One Step at a Time program.

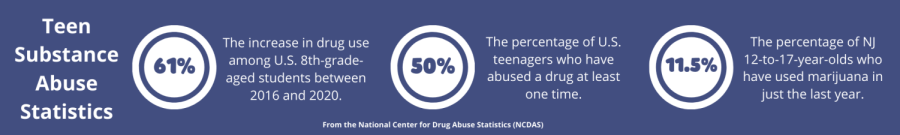

Mr. Anthony Saporito, the Cherry Hill Public Schools Director of Security, reports yearly statistics for the number of students that have been sent out for drug/alcohol testing, after showing signs of being under the influence, and that have had those tests come back positive. During the 2020-21 school year, there was only one positive test returned. Yet, this number may not take into account the students that were reliant on substances, but were simply not showing signs because of the isolation that online school provided.

Jean’s Story

In 2019, Jean Adams* (‘24) was in seventh grade. Her mom was an alcoholic, and sometimes her mom gave her some drugs, but it was nothing big, she said. It just started with her friends. Drugs made her carefree. Happy. Numb. But when she started having mental health challenges — depression and anxiety — drugs were a way out. The easy way out.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, research indicates that over 60% of adolescents who are in community-based treatment programs for substance use disorders also meet the criteria for another mental illness.

DiStefano emphasized that because substance use disorders may be comorbid with other mental health illnesses, referring students to outside experts is the best way to get an accurate diagnosis.

In eighth grade, due to the isolation Adams felt from COVID-19, she continued to turn to weed, and at one point was using it every day.

I didn’t really have any expectation for myself to get better.

— Jean Adams ('24)

“I didn’t really have any expectation for myself to get better,” she said.

At the beginning of her freshman year, Adams stopped using weed during her sports seasons but continued drinking heavily. Slacking off. Showing up hungover. And her coaches didn’t realize.

Adams added that the “party culture” amongst many East students made it easier for her to use substances.

“I’d go to a party and parents would be giving out alcohol,” she said, showing the alarming accessibility of substances for students at East.

But after a traumatic event where she was taken advantage of while under the influence, she realized that substances were worsening her life and taking her down the wrong path. The recovery process for Adams was long and hard, and she relapsed along the way. While initially in a toxic friend group that pressured her to try new substances, she separated herself from all of those friends after becoming clean.

At the end of the day, who’s going to be there when you graduate high school? Yourself.

— Jean Adams ('24)

“At the end of the day, who’s going to be there when you graduate high school? Yourself,” Adams said.

When asked if she had a support system at East while she was using, Adams had a one word answer: No. Noting that it may have been due to COVID, she said that she doesn’t remember being taught anything that impacted her enough to make her try to change her life before recovery.

Students who are struggling need to know how to reach out for help and take advantage of the support systems in place at East, Hildebrand said.

Meredith Cohen, the Director of Special Projects and Compliance for the JFCS, said, “At some point, when a young person is faced with a very difficult decision: do I try something because I want to fit in, because I am too afraid to speak up, because I want to look cool, because I want to prove that I know how to party and have fun, because I have feelings that I am trying to stuff, because there [are] issues in my family and I don’t want to deal with them anymore, because I am flunking a class, they say stop, and think to themselves… I remember what can happen.”

Hildebrand also often reminds students to talk to a trusted adult if they know someone that is struggling. She talks to her students about being a good friend and support person. Adams added that Harris helped give her advice throughout her journey.

To anyone that is struggling with substance use disorders, Adams said, “There is [a] life worth living. We are teenagers. We are young… Just focus on yourself. Don’t care about the whole thing… the whole everybody. Focus on you.”

*Names changed to protect identity

Gia, a Print Editor-In-Chief, loves stargazing, asking questions to strangers, and wandering in bookstores. Some of her favorite things include The Marginalian,...