The African crisis: A continent plagued by colonization, corruption, and conflict

Many African nations struggle with poverty, weak governments, and economic instability due to centuries of colonization and exploitation. European powers, like Britain, France, and Portugal, controlled African lands, extracting valuable resources like gold, diamonds, and oil while offering little investment in local economies, harming the people who inhabited these lands. When African nations gained independence in the mid-20th century, they were left with unstable governments, social conflicts, and economies designed to serve foreign interests rather than their own people.

Corrupt leadership, often influenced by colonial rule, continues to be a problem. Some African governments misuse resources, prioritizing wealth over infrastructure, education, and healthcare. Foreign corporations also contribute to underdevelopment by exploiting Africa’s natural wealth while providing low wages and poor working conditions. Countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is incredibly rich in minerals used in modern technology, see little benefit from these resources as profits often go to multinational companies, mostly Chinese corporations.

Despite these challenges, some nations are working to overcome the damage of colonization. Ghana has invested in technology and industry, with its government placing full focus on start-up ecosystems and fostering growth of tech hubs across the country. Rwanda has focused on rebuilding after genocide through economic reforms and development programs. However, many African nations still struggle to break free from the economic and political effects of their colonial past.

Furthermore, weak infrastructure, poor healthcare systems, and food insecurity make natural disasters and humanitarian crises more devastating in Africa. Governments often lack the resources to prepare for or respond to these emergencies, leading to higher casualties and slower recovery.

Droughts frequently lead to severe food shortages, particularly in East Africa. Countries like Somalia and Ethiopia struggle with recurring droughts that destroy crops and leave millions at risk of starvation. Without irrigation systems or proper food storage, communities cannot recover quickly, making each drought worse than the last.

Disease outbreaks spread rapidly in areas with weak healthcare systems. The 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa killed over 11,000 people, partly due to a lack of medical supplies and trained professionals. Cholera remains a major problem in places like Sudan and Mozambique, where limited access to clean water and sanitation fuels frequent outbreaks.

Natural disasters cause lasting damage when infrastructure is weak. In 2019, Cyclone Idai struck Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Malawi, killing over 1,000 people and displacing millions. Poorly built homes, a lack of drainage systems, and weak emergency response teams made the disaster far deadlier. Floods and cyclones regularly destroy entire communities, leaving people without shelter, food, or clean water for weeks.

Efforts to improve healthcare, food production, and disaster preparedness are ongoing, but underdevelopment continues to make these crises more severe. Without long term investment, recovery remains slow, and future disasters will only bring more destruction.

In the 19th century, Cameroon suffered the same unfortunate fate as many other African countries: European colonization. Initially a German protectorate, Cameroon was divided into two parts under Britain and France after Germany’s loss in World War I, leading to an intense cultural divide over lingual, ethnic, and religious differences. When Africa’s decolonization began in the late 1950s, these divides remained an issue for Cameroon, which was culturally and politically split along the former colonial borders between French Cameroon and the Anglophone states.

Particularly controversial was the elimination of federalism in the United Republic of Cameroon, which had been the political system of the Anglophone states under British rule. As the minority in the new republic, many Anglophones felt that they had become a marginalized people under the centralized power of the largely French Cameroonian government. Under Cameroon’s second and current president, Paul Biya, the situation only worsened as French Cameroonians dominated the country, not only in politics, but in education, language, and occupations.

“He’s almost 95 years old and he’s still in power,” Darius Kogah, a 17-year-old Cameroonian immigrant, said in an interview with Eastside, “so it raises a lot of concern why the president would want that much power and would want to rule and lead a country full of corruption.”

Biya, who has been in power since 1982, became heavily controversial because of his refusal to concede power and allegations that he had only maintained his office through unfair elections. Outraged with the government’s imposition of French teachers and lawyers in schools and courts in 2016, many Anglophones took to the streets in peaceful protests to call for the restoration of federalism, but were ultimately met with violent military force and mass arrests. As a result, the Anglophone Crisis began as the protests escalated into armed conflict and secessionist groups declared the independence of the “Federal Republic of Ambazonia” in Cameroon’s northwest and southwest.

“It’s the tiredness of inaction… of no change being made because the civil war which is ongoing didn’t just start out of nowhere. It started with very small protests that then led to violent crimes,” Kogah said in regard to the reasons behind the Anglophone Crisis. “We got impatient and the rebels had to do something… they saw that words weren’t helping, so they had to take physical action.”

Biya never acknowledged the independence of Ambazonia, only promising to crush their rebellion with the deployment of the Cameroonian army into the Anglophone regions. The resulting Ambazonia War has left over 6,000 civilians dead and millions displaced as the Ambazonia Defense Forces and Cameroonian military battle for control. The Ambazonia Defense Forces, often referred to as the Amba boys, are responsible for some of the most heinous atrocities of the war.

“They use very violent techniques like hurting people with machetes which is very slow and painful [compared to] a simple gunshot,” Kogah said. “The Amba Boys… have done horrible things which include someone being ripped apart into four pieces with bikes, a security guard’s head being chopped off, schools being raided, a lot of people being displaced, and shops being burned. It has even gone to the extent of a person being shot in the face and left to suffer.”

The violence experienced by civilians, particularly in Anglophone regions, has been largely due to efforts by the Amba boys to assert power over the Cameroonian government through kidnappings and ransom demands.

“The need for the money is to help fund the war because they’re rebels,” Kogah said. “They’re not part of the military… so they don’t have government funds to fund the war.”

A major method employed by the Amba boys targets schools as a form of protest against government imposition of French language and teachers even in Anglophone schools. Hundreds of schools across Cameroon have been burned, destroyed, or otherwise attacked by separatist groups like the Amba boys, sometimes even developing into large-scale kidnappings like the 2018 Bamenda kidnapping in which 81 students and teachers were taken hostage.

“They’ve been getting a lot more weapons and that has led to them attacking more people, innocent or not, and heightening the fierceness of the war,” Kogah said, “which is continually destroying cities like Bamenda, which I grew up in, and even the capital, Yaoundé.”

Ultimately, the extreme divide in Cameroon was a direct result of European colonization and its effects can still be seen and felt within the country centuries later. Without the initial stability to grow properly as a country, Cameroon was doomed to conflict from the moment decolonization began, much like many of the other countries plagued by violence in Africa. As Cameroon continues to struggle with internal conflict, external diplomatic intervention from other nations across the world seems more and more like the only solution to halt the unceasing violence and finally mend the division.

The boarding schools of Bamenda, Cameroon — with their high fences and security guards — had always been regarded as relatively safe from the conflicts of Cameroon’s Ambazonia War. However, on Nov. 4, 2018, that illusion shattered with the kidnapping of 81 students and teachers from Bamenda’s Presbyterian Secondary School. In Cameroon’s worsening civil war, even classrooms had become battlegrounds. One student from among the kidnapped, 17-year-old Darius Kogah, seized the chance to escape the conflict, immigrating to the U.S. with his family to pursue a higher education. Eastside interviewed Kogah, who shared his experiences in the hopes of bringing awareness to the conflicts in his home country. Here is his story.

At 9 years old, Kogah’s parents sent him to Bamenda’s Presbyterian Secondary School, which he believed to be safe, but nevertheless prison-like. Every morning, they would bathe in cold water because hot water was unavailable, and among the students, there was an unofficial hierarchy that gave students with higher forms — meaning classes or grades — more control over those with lower forms.

“The living conditions were comparable to a prison in America because the food was meager, the walls [were] high, and it was very indistinguishable from a cell,” Kogah said.

Outside of the confines of his school though, Kogah knew that there were much larger issues as a result of the ongoing Anglophone Crisis, otherwise known as the Ambazonia War, between the French Cameroonian government and the Ambazonia Defense Forces that consisted largely of the country’s Anglophone minority. Despite Kogah’s belief that the school would protect him from the violence beyond its walls, the day ultimately came on Nov. 4, 2018, when members of the Ambazonia Defense Forces, often referred to as the Amba boys, broke into his boarding school and began rounding up students and teachers.

“We were in school and the classes were going as usual until we started hearing gunshots and commands from the Ambazonia boys,” Kogah said, “and [at] this point, we were pulled out of the classrooms and taken to… the soccer field.”

Kogah was among the 81 students and teachers kidnapped and used to demand that the Cameroonian government close the school as a form of protest against the government’s imposition of French teachers and language in Anglophone schools. Upon transporting the students to an unknown location, the Amba boys released a video on social media in which they forced several of the kidnapped children to say their names and the names of their parents to prove the severity of the situation to the Cameroonian government. Although the Cameroonian authorities dispatched search parties to find the students, they were unsuccessful and the government made little effort otherwise to resolve the situation or negotiate with the kidnappers.

“[The Amba boys] would use force like maybe killing a hostage to show the seriousness of the situation,” Kogah said when asked about his thoughts during the kidnapping. “I thought it was my end.”

Eventually, through a series of negotiations with the Presbyterian Church of Cameroon, the students were peacefully released on Nov. 7, 2018 in an abandoned church building roughly 15 miles from Bamenda. However, the Amba boys did achieve their goal, as the school was closed down shortly after the students’ release. Even though the Cameroonian authorities had been unable to locate the students or otherwise resolve the situation, they took credit for the students’ release.

“When I heard that I was free… that was a life-changing moment,” Kogah said, “and it really changed the kind of person I am today to be someone who values life and is empathetic about situations people could be facing.”

Following his release, Kogah and his family faced the difficult decision of whether to remain in Cameroon or immigrate to the U.S. for their safety. Kogah’s father was a principal of a local school, which made life even more dangerous for them, as anyone with such influence over schools immediately became a target of the Amba boys. Despite the heightening war, Kogah’s parents valued academics more than anything, which ultimately led them to immigrate to the U.S. so that their children could pursue a higher education without the risks associated with it in Cameroon. However, life after immigrating to the U.S. wasn’t exactly easy for Kogah either.

“Life was tough coming from a place where… everyone looked like me, everyone spoke like me, and we ate the same foods,” Kogah said. “It was hard to adapt particularly in middle school because my accent was always stronger than everyone else’s, my skin was always darker, and I just didn’t act the way people acted.”

In spite of his initial struggles to adjust to his new school and environment, Kogah now excels academically as a senior at the Academy for College and Career Exploration in Baltimore, avidly participating in his school’s wrestling and robotics teams along with an array of other extracurriculars.

“I’m very grateful for the opportunity to pursue my further education in the United States,” Kogah said. “The [college] process has been fun because I’ve been able to look at my story which I never knew I had.”

While Kogah was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to move to the U.S., the sad reality is that most Cameroonians suffering from the violence of the Anglophone Crisis don’t share the same privilege. How many children must be stolen from their desks before people recognize the need for change? How many hostages must die? How many schools will be burned? There must be greater diplomatic efforts within Cameroon, and by other nations across the globe, to cease the violence and division between French Cameroonians and the Anglophones. Otherwise, the world risks allowing another generation of Cameroonian children to grow up — not fearing the monsters in their closets — but the machetes and guns of their brethren.

Many people in the U.S. today face increasing prices due to inflation, working jobs tirelessly to make ends meet. Individuals living in Sierra Leone, a country in West Africa, can relate to this problem, as they deal with steep inflation within their economy. In this story, Eastside interviewed an immigrant and student at East from Sierra Leone, who chose to stay anonymous, but shared his experience dealing with inflation in his home country.

After living most of his life in Sierra Leone, the student moved to Cherry Hill, NJ approximately three years ago. During his time there, inflation was easily the biggest problem he and his family faced.

“There is an overprice of goods,” said the anonymous student. “People there… are poor because the prices are high.”

Inflation of food prices in Sierra Leone has been a great concern, with a 14.78% increase in the cost of food in January 2025 compared to the previous year. Reasons for the high inflation include loose fiscal taxes and monetary policies. Moreover, although Sierra Leone is supposed to have a tight macroeconomic policy to allow for disinflation, they have been neglected in recent years, causing further inflation.

However, it’s not just grocery prices that are affected by inflation.

“For everything — medicine, groceries, all of that… as a whole — it’s mostly about inflation,” said the student. “It’s not just one thing overpriced. It’s every single thing.”

In Sierra Leone, the healthcare system faces multiple challenges due to inflation, including rising costs for medicines and medical supplies. These changes could easily lead to financial strain for patients and potentially hinder access to essential healthcare services.

The student expressed his wishes for the government to lower prices to help the people, saying that “the government should make it user-friendly for everyone [and] make laws to lower the price to help the actual people of the country.”

Inflation also affects the public school system.

“It’s not bad, but it’s [worse] than here,” the student said. “It’s mostly bad since there is a lack of materials for students.”

Inadequate government funding has led to supply shortages, untrained teachers, and the general low quality of school systems. These problems make it significantly harder for students to learn what they need to.

“They don’t have the right materials for school, so kids struggle for education,” said the student.

Sierra Leone faces low literacy rates with only 37.1% of adults being literate. Furthermore, there are high dropout rates, with only 64% of students finishing primary school, 44% finishing junior secondary school, and 22% finishing senior secondary school. In some circumstances, children drop out of school to have more time to work at a job to support their families. However, finding a job can be an equally daunting challenge.

“There are… no more jobs there,” said the student, “and if you can’t work, you can’t get money, making it harder for the people.”

A substantial portion of the youth population — about 70% — are either unemployed or underemployed, making it challenging for families to earn money. A major contributing factor to the lack of employment is the country’s civil war, which lasted from 1991 to 2002 and devastated the country’s economy. Another factor, the Ebola epidemic, lasted from 2014 to 2016 and further disrupted the economy with a decrease in available jobs. In addition, the lack of education causes many young individuals to struggle with securing employment.

In the future, the student hopes for more job opportunities, saying that “they need to bring more jobs for the people.”

Lastly, there are problems with the infrastructure, specifically with road infrastructure.

“It’s actually poor. I want to see a couple of changes,” said the student. “The roads are mostly rocky… and rough. It’s just not smooth and it’s so dusty.”

The country’s civil war severely damaged many of the roads, and a large percentage of roads are unpaved, hindering access to markets and preventing economic development.

Many issues stem from the government’s neglect for the people, a failure that the student also holds them accountable for.

“Mostly, the government is selfish. They just care about themselves and not the people,” said the student, expressing his desire for the government to change their perspective for the people. “Basically [wanting] equality for all. Have the right to be able to buy stuff you want.”

As Sierra Leone continues to navigate these economic and social struggles, the anonymous student hopes for a meaningful change in the country.

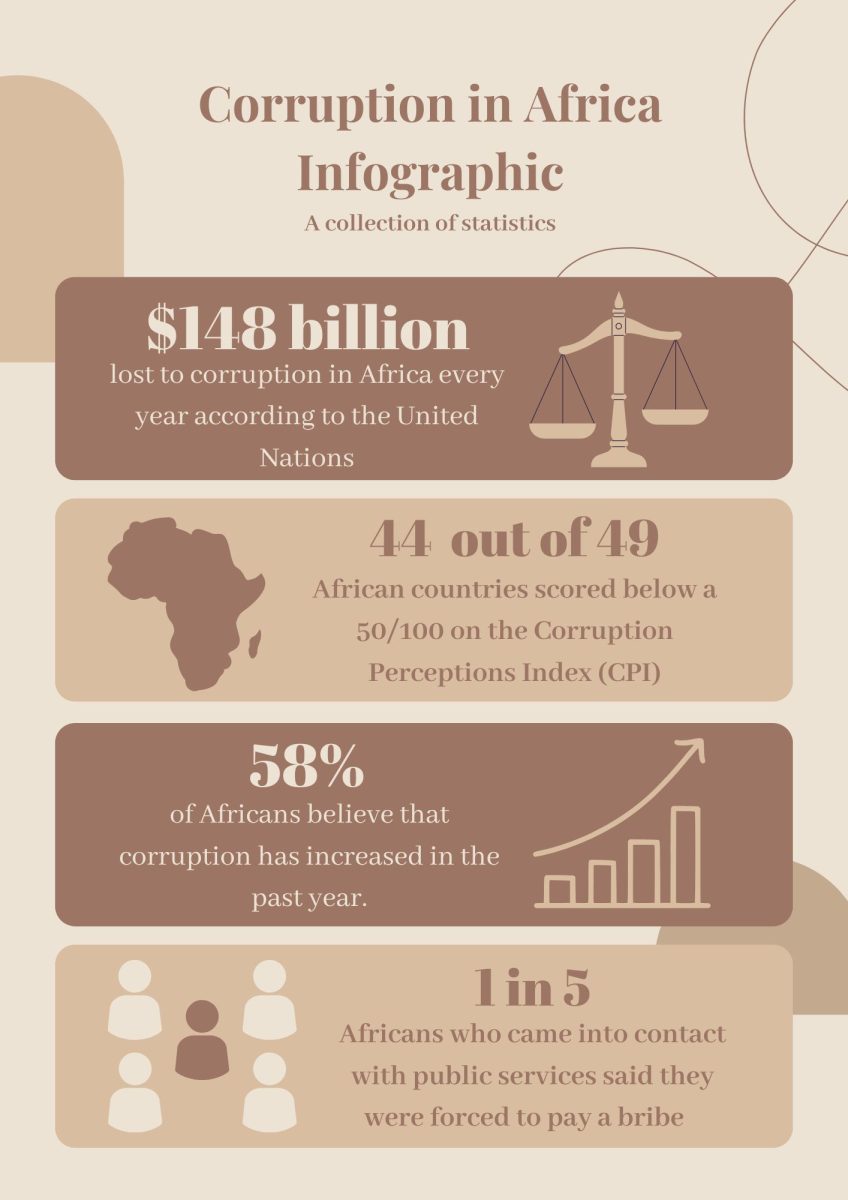

By definition, corruption is dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power, resulting in individuals abusing their power. Corruption is a prevalent issue within Africa, with many authoritarian leaders staying in power for over 30 years, diminishing true democracy in most African countries. These are some of the longest serving African leaders.

Equatorial Guinea (45 years)

The longest serving African leader is Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who seized power in 1979 from his uncle, Francis Macias Nguema in a coup. Macias’ rule was extremely brutal, with many reports of human rights abuses. Obiang reportedly began plotting with family members to overthrow the president after his brother was put to death. The bloody coup, known as the “coup for freedom,” was successfully carried out on Aug. 3, 1979, resulting in Macias’ trial and execution in September 1979.

Unfortunately, any hope that Obiang’s rule would be different from his uncle was swiftly lost. He created the illusion of democratic reform through the creation of a new constitution in 1982 with the help from the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The new constitution granted Obiang a seven year term as president and gave him far-reaching powers. In 1991, he created another constitution, which allowed multiple political parties. However, the constitution also eliminated the last few human rights protections that had existed under the previous constitution. It also granted Obiang immunity, stating that he cannot be prosecuted for anything. In the next four elections, Obiang won all of his reelections — with all of them being denounced as fraudulent.

Multiple countries, such as the U.S., France, Switzerland, and Spain have conducted investigations into allegations of corruption among high officials in Equatorial Guinea, including the Obiang family. French authorities convicted Obiang’s son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, for money laundering and embezzlement in an investigation from 2008. The U.S Department of Justice settled a corruption case against Obiang Mangue as well, resulting in a forfeit of his assets. Despite this, there continues to be reports of restricted personal freedoms, harassment of opposition members, unlawful arrests, forced disappearances, and torture throughout the country.

Cameroon (42 years)

The second longest serving African leader, Paul Biya, came to power on Nov. 6, 1982, after the first president of Cameroon, Ahmadou Babtoura Ahidjo, unexpectedly resigned. Biya was originally the fifth prime minister under Ahidjo from 1975 to 1982, paving the way for him to become the president’s constitutional successor.

In 2023, approximately 23% of Cameroonians lived below the international poverty line, with poverty rates particularly high in rural areas and the northern regions. Yet, Biya — along with his court of ministers and assistants — travel frequently, especially to Switzerland where they stay at one of the most luxurious hotels in Geneva at the expense of the Cameroonian people. The people face infrastructure challenges such as poor roads and unreliable electricity. Although infrastructure is progressing in the country, it is low compared to other sub-Saharan African countries.

Biya has been accused of rigging elections to stay in power, using fraud, intimidation, and vote suppression. During his first two reelections in 1984 and 1988, he ran unopposed and abolished the prime minister position, keeping more power to himself until 1991, when the position returned. During the first multiparty election in 1992, he was further accused of fraudulent votes. He continues to be marred by accusations of election rigging, especially with his most recent reelection in 2018.

Despite being 91 years old, Biya plans to run for another presidential term in 2025 and will most likely win, as the government shuts down political opposition. Peaceful protests by opposition groups are frequently met with brutal crackdowns by police and military forces. In 2020, protests against Biya’s rule were violently suppressed, leading to dozens of arrests and allegations of torture and mistreatment by detainees. Maurice Kamto, the leader of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement and Biya’s main opponent in the 2018 reelection, was arrested in 2019 after leading protests against alleged election fraud. He was imprisoned for 9 months before being released as a result of international pressure. Although under strict global surveillance, it is expected for Paul Biya to continue to stay in power.

Republic of the Congo (40 years)

The third longest serving African leader is Denis Sassou-Nguesso, a former military leader who served twice as president from 1979 to 1992 and 1997 to the present. Pascal Lissouba served between 1992 and 1997 and was the first democratically elected president of the Republic of the Congo. A two-year civil war broke out between the government troops loyal to Lissouba and the private militia of Sassou-Nguesso. Sassou-Nguesso managed to seize the city of Brazzaville, allowing him to overthrow Lissouba, who later fled the country.

Once Sassou-Nguesso came back into power, he implemented a series of economic and political reforms to help the country survive from bankruptcy and strengthen the democratic process. However, many opposition groups questioned his democratic reforms. When he was reelected in 2002, some boycotted the race, claiming that the democratic reform was still lacking and that the election was unfair.

In December 2008, Sassou-Nguesso, along with the presidents of Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, were targets of a lawsuit accusing them of the misuse of public funds, embezzlement, and money laundering in connection with a luxury property in France. However, the allegations did not seem to bother Sassou-Nguesso as he prepared for the 2009 election. The election was again boycotted by the main opposition, yet Sassou-Nguesso won by large majority. Although some organizations claim that there were incidents of fraud and intimidation, internal observers from the African Union declared the election as fair.

In 2015, a proposal came forth to amend the constitution to eliminate term limits and raise the maximum age for a presidential candidate, which would allow Sassou-Nguesso to remain in office. Officials reported that 92% indicated that they were in favor of the proposal. Thus, Sassou-Nguesso will likely continue to win elections despite the constant boycotts from opposition and allegations of fraud in the 2016 and 2021 elections.

Uganda (39 years)

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni Tibuhaburwa is the fourth longest serving African leader and the ninth president of Uganda. In 1980, Museveni ran for president but lost to Milton Obote. Believing the election to be rigged, Museveni and former president Yusufu Lule formed the National Resistance Movement (NRM). Museveni led the NRM’s armed group to wage a war against Obote’s regime. The resistance prevailed on Jan. 26, 1986, and Museveni declared himself as president. He was then officially elected to office on May 9, 1996, and his supporters won control of the National Assembly.

Museveni was reelected in 2001 and 2006 after a constitutional amendment was passed to eliminate established term limits for presidency. He was again reelected in 2011 and 2016, but opposition suspected him of fraudulent polling in both elections. Another constitutional amendment was passed in 2017, removing the age limit for presidential candidates that was previously set at 75 years old. The amendment also reimposed a limit of two terms, allowing Museveni to run for president for the next two elections.

During Museveni’s presidency, his intolerance of dissenting views grew. As Museveni continues to hold power, opposition figures and their supporters have reportedly been harrassed, detained, and even abducted. Kizza Besigye, a long-time opponent of Museveni, has been arrested multiple times and placed under house arrest after challenging the president in elections. Likewise, Robert Kyagulanyi, who goes by the stage name Bobi Wine, is an opposition leader and musician who has faced numerous arrests, torture, and restrictions on his movement. In 2018, he was brutally beaten and detained after organizing an anti-government protest. In 2021, after losing the presidential election to Museveni and claiming Museveni used fraud and intimidation, he was suddenly placed under house arrest.

These ongoing patterns of repression highlight Museveni’s tightening grip on power, where opposition voices are systematically silenced through intimidation, violence, and unjust detentions.

Ultimately, these African leaders, through their fraudulent and dishonest actions, showcase the deeply rooted corruption within each country. The constant electoral manipulation and systematic suppression perpetuates the suffering and marginalization of millions across the continent.

For most, if not all, of the 21st century, Africa — specifically regions known as the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Lake Chad Basin (centre-northeast) — has felt the presence of Islamist extremist groups. Groups such as Al-Shaabab, Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State operate in countries like Nigeria, Somalia, Mali and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), aiming to not just restore, but expand the Caliphates that existed during the Golden Age of Islam (8-13th centuries). Using tactics like mass execution and torture, these terrorist groups have “deliberately murdered more Christians… in Nigeria’s Northern and Central belts than in all of the Middle East combined,” according to an ongoing study sponsored by the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom. Through ethnic cleansing and slaughtering of whole villages, these terrorist groups have destabilized a region already weakened due mainly to government instability and corruption.

As previously mentioned, the main Islamist groups include Al-Shaabab, Boko Haram, and the Islamic State. While they are independent entities, both Al-Shaabab and Boko Haram have pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, forming one united front to take over the African continent. These groups, as well as affiliated groups such as the Allied Democratic Front (ADF) in the DRC, regularly carry out attacks on Christian villages, beheading entire families and selling young women into slavery. In February 2025, the ADF took over the Christian village of Mayba in the DRC, decapitating 70 members. In the Benue State, years of attacks have left close to three million people displaced. In a video taken from the phone of a Christian woman, Chukwuemeka Offor, she is heard saying, “our women are raped by [Islamist] herdsmen[.] Our husbands don’t go to farm again, our son’s don’t go to farm again, when the women go to farm, they will be beaten by the herdsmen, rape[d].”

In early March, it was reported that nearly 200 Christians were taken hostage near the Nigerian city of Rijana. The few sole escapees were starved for 85 days. Current hostages include schoolgirls and pastors, whose only crime was being Christian.

Everyday, Christians are being persecuted by Islamists, yet human rights organizations like the United Nations and the International Criminal Court, as well as major news outlets like the British Broadcasting Corporation raise very little awareness on these situations. Every day, the same people that are being persecuted are calling out to end the silence, referring to their own struggles as ‘silent.’ Christians berate the Pope online for writing books about the Gaza-Israel war rather than speaking up for the Christians he supposedly represents. The world is silent as Africa is taken over in ‘His name,’ and there is barely a peep. The entire world turns a blind eye because it is what is comfortable, not because it is what’s right.