I visited the Princeton University Encampment. Here’s what I saw and heard from the protesters.

At first, the encampment was quiet, and students scattered here and there as they walked to their destinations. The closer I got to the protest, I heard the sounds of a drum beating and cowbells ringing. When I first arrived, my impression was underwhelming, to say the least. While I was expecting riots and massive swarms of people, I instead was greeted to what could only be described as a picnic.

Students sprawled out in the sun on the lawn, enjoying hot catered food being distributed. Walking the border of the encampment, signs and banners covered the trees. Some students were playing soccer, while others sat around in beach chairs, talking. Although the scene was nothing to be scared of, there was an eerie feeling. The first student I walked up to was a young man with long curly hair, smoking a cigarette. He did not look too engaged, so I figured he wouldn’t be too busy to answer a few questions.

I asked to interview him, and he told me that he was uncomfortable talking about the topic. He then proceeded to direct me to an encampment organizer. These organizers wore yellow vests and were charged with securing the border of the encampment and “ensuring the safety of everyone” amongst numerous other tasks. The next person I talked also informed me that he was also not equipped to answer me and refused an interview. He then directed me to my first successful interviewee: Angel.

The first individual I spoke to was Angel, a student at the Princeton Theological Seminary. Angel told me that she “shares similar struggles [as Princeton University] in working towards a divestment and a Free Palestine.” When I asked her what ‘struggles’ she and other protesters were facing, she did not directly answer the question. “[Our goal is to] get the administration to work towards a divestment from [Israeli and/or Israeli supportive companies] that bomb Palestinians,” Angel said.

Next, I walked over to an individual who I hoped could provide me with more insight. After accepting my interview, the communications liaison for the encampment walked over and told him that he was actually super busy with meetings. Perfect timing, coincidentally, of course. My frustration was beginning to grow. Why could nobody able to give me any definitive or specific answers? How come none of the protesters wanted to speak with members of the media?

I went to walk to another organizer. Multiple people had been directing me to these yellow-vested leaders who were supposed to be mouthpieces for the protest. As I approached the supervisor, she told me she was very busy with extremely important work. Although I have no proof of what she was doing, I had been watching her for the previous five minutes to scout out what my interviewee would be like, and she clearly was not wrapped up in urgent work.

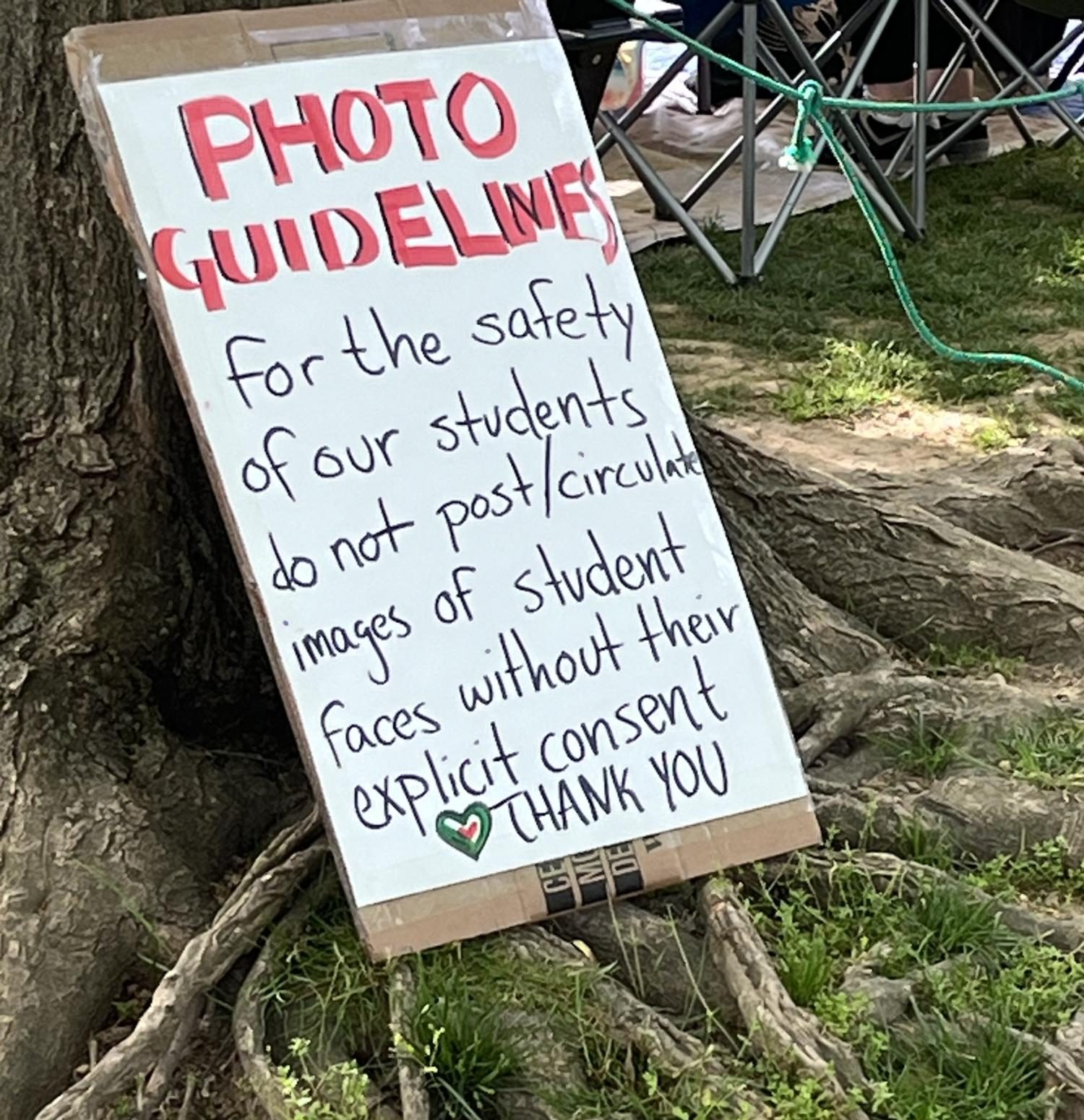

After I asked her if she could take a few questions, she told me that I was harassing her. She then put her mask on. While some fellow campers came to question what I was doing, I was greeted by an individual named Jeremy. Jeremy tells me that I had engaged in harassing behavior and had disobeyed the encampment photo guidelines. He then asked me to leave.

Before I left, I noticed a table cross from the encampment. It was a Passover table manned by a family holding up signs of Israeli hostages. One of the signs said “rape is not resistance.” Every single member of this small group was willing to be interviewed and explain what they were doing. Only one individual out of an entire encampment of pro-Palestine protestors, however, was able to speak.

According to NXIVM cult survivor Sarah Edmonson, a cult is a high-control group with a seemingly altruistic mission to change the world through the use of coercion, obligation, gaslighting, and control. “Cults thrive on your desire for connection, meaning, and purpose,” says Edmonson.

Edmonson list six different signs of a cult. They include:

- Assumption of Neediness

- Expensive (could cost time, relationships, money)

- Loaded Language

- Lawsuits or bad press

- Definitive answers

- No questions welcomed

Many groups and protest efforts throughout history have demonstrated one or two of these signs. The pro-Palestine encampment at Princeton University clearly demonstrated all six.

Assumption of Neediness: The encampment thrives on the idea that people, particularly the Gazan residents, need them. Hamas recently released a propaganda video; in the video, Gazan children thank the protestors. Furthermore, because the encampment needs people to pay attention to their efforts, student protesters make the situation on campus so unbearable that other students feel compelled to join their cause. The Princeton encampment sends a message to Princeton students and faculty that they must join their cause, or grave things will occur.

Expensive: For these encampments to function, they rely on money and time. Encampments across the country regularly release lists, in which they ask for hot food and supplies. Such supplies include tents, sleeping bags, riot gear, Aquaphor, and more, all of which they allegedly need to stand in solidarity with Palestine. Where do these encampments get their food and supplies? Organizations such as the Tides Foundation, WESPAC, Jewish Voice for Peace, and American Muslims for Palestine all contribute to the encampment funds.

Loaded Language: These encampments often use vague rhetoric to influence their audience. When I was asking people to be interviewed, for example, one organizer, who identified as Jeremy, told me that if I was disagreeable, the encampment would have ways to disengage with me. The encampment refers to any and all they disagree with as Zionists. Terms such as genocide, colonization, and divestment are thrown around at these encampments very frequently, without proper consideration of their connotations and meaning. In the Princeton encampment, students are told to tell members of the press to “go speak to the organizers.” Rules have been established within the encampment where protesters cannot speak with journalists; protesters are instructed to say phrases over and over again until media leaves.

Lawsuits or Bad Press: Currently, the “National Students for Justice in Palestine,” an organization that has contributed to encampment efforts across the nation, is facing lawsuits from nine survivors of the October 7th attacks. During the attack, 1200 Israelis were killed and over 200 taken hostage. Additionally, Students for Justice for in Palestine (SJP), another group enabling and supporting encampments, is facing terrible press. Many news sources and politicians have condemned the protests for leading to the incitement of violence, perpetuating antisemitism and discriminatory rhetoric, and vandalizing school property.

Definitive Answers: Organizations such as SJP and Jewish Voice for Peace push a single narrative: Zionism is white, oppressive colonialism. Furthermore, these organizations aim themselves at attacking Zionism. In their understanding, those who identify as Zionists are evil and should not be engaged with on any level. These definitive answers, which do not allow for leeway, are often narratives pushed by terrorist organizations, such as Hamas.

No Questions Welcomed: This sign is very similar to Definitive Answers. The Princeton encampment, as I experienced, challenges and negates all alternative thoughts and opinions, isolating itself in its own echo chamber. It also means refusing to answer questions from those they do not know or are not familiar with. When I attempted to interview some protestors, they refused to welcome my questions. The message was clear: the protesters were in no business of speaking about their efforts and were solely intent on keeping to themselves.