Education deserts cause difficulty in achieving a higher education

As of 2019, approximately 35 million Americans live in deserts. Not deserts characterized by scorching sun, dust storms, and camels, but education deserts. Similar to glimmering oases among sand dunes, in education deserts, opportunities for higher education are few and far in between.

Each year, regardless of the educational topography of their hometowns, millions of American high schoolers set off on the search for a higher education. Although many picture this journey as one of a young adult “leaving the nest” to flock miles away to a new college or university, in reality, traveling far for school is a privilege, not the norm. Like the familiar real estate refrain, “location, location, location” is a key factor in many students’ college decisions and consequently, distance has become an all-too-common barrier to college enrollment. In fact, two out of three undergraduates stay close to their roots and attend a college within 25 miles of their home, according to a study conducted by the U.S. Department of Education. Staying local might not pose much of an issue if educational resources and opportunities were evenly distributed throughout the country, but this is not the case. While some regions flourish as havens for academia, others remain highly under-resourced.

So, what happens if a student resides in a region where higher education is largely inaccessible? How exactly does a student quench a thirst for knowledge and learning when their surroundings are dry of opportunity?

Thus arises the issue of higher education deserts. A higher education desert can be defined as an area where there is either zero or only one broad-access public college nearby. While there is no definite rule, a college is typically considered to be broad-access if it has an acceptance rate of 80% or higher. In higher education deserts, students may only have one accessible college within commuting distance and even then, accessibility may be strained. In Montana, for instance, one in three residents lives over 60 minutes from the nearest college campus.

Inaccessibility isn’t the only issue plaguing education deserts. When there is only one broadly-accessible college serving multiple commuting zones, the school is forced to spread its resources thin and the strength of the education it provides to its students diminishes. For example, schools in education deserts struggle to deliver as many services – from financial aid to courses to academic support – to its students compared to schools in better resourced areas.

Furthermore, when it comes to the American education system, all are not created equal. Education deserts disproportionately affect certain groups and exacerbate many already existing economic, racial, and geographic disparities. Studies show that while white and wealthy students are most likely to migrate out-of-state for college, most other students – especially Black, Hispanic, or low-income students – are less likely to attend a college the farther it is from home. Thus, those with less educational mobility are more susceptible to the consequences of geographical disparities and inequalities. Furthermore, because education has long been considered perhaps the greatest tool for social mobility, the system of education deserts creates a reinforcing feedback loop with today’s existing systemic imbalances.

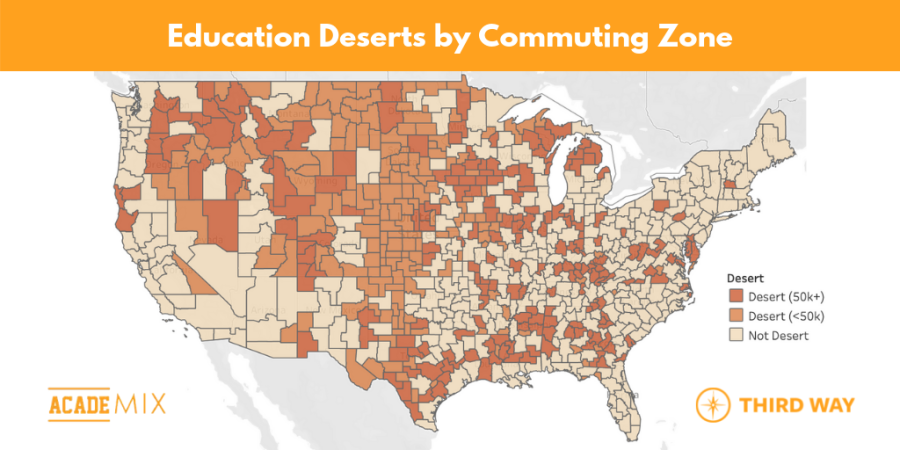

A study by Third Way, a public policy think tank, finds that 392 of the 709 commuting zones in the U.S. are classified as higher education deserts, accounting for about 10% of the nation’s population. Notably, education deserts are quite concentrated in rural regions (just shy of half of the education deserts identified in the Third Way study were located in commuting zones with populations less than 26,000), more so than in urban areas, further widening the education gap between rural and urban America.

“People will say, ‘That’s so elementary,’” Nick Hillman, the author of the Third Way report, said in an interview with U.S. News. “The entire state of Wyoming is a desert, big surprise. There are no colleges in Yellowstone National Park. But we can dig down deeper.”

To be sure, higher education deserts are also present in locations of higher population, with over 200 deserts in zones with populations of nearly 180,000. Furthermore, Hillman’s report also uncovered that educational opportunity can be lacking even in cities that seem to be brimming with academic activity.

For example, with well-known universities such as UChicago and Loyola University, Chicago may seem like an oasis for the pursuit of education. However, most of the colleges that call Chicago home are selective private schools. Although Chicago does have quite a few two-year public colleges, it has zero broadly-accessible four-year colleges, making it difficult for underprivileged local students to receive an extensive education while also fulfilling local responsibilities, such as taking care of family.

Furthermore, as with our natural landscape, the educational landscape of the U.S. isn’t simply just desert or not desert. Social scientists use various geographic metaphors to describe the spectrum of educational opportunity. Cities like Chicago are classified as mirages: they are regions with multiple higher education options, giving the false appearance of plentiful educational opportunities when in reality the available schools are often too selective to actually enroll many students. Studies estimate that 124 commuting zones, which is 17% of the total U.S. zones, are educational mirages.

Additionally, a refuge is defined as a community where higher education options may not be high in number, but the existing options are highly accessible and available to many students. And of course, the ideal educational climate is an oasis: an area where there are plenty of public, broad-access higher education options.

But, what can be done to irrigate education deserts? Throughout the years, online schools have emerged as a common proposal for ensuring higher education to students located in under-resourced regions is online school. Yet, even with the seemingly ubiquitous nature of the Internet and technology today, this proposed solution is not unaffected by the geographical disparities. In fact, compared to approximately 75 percent of people in urban regions, only about 63 percent of people in rural areas have broadband internet access in their homes, making them more prone to infrastructure complications when pursuing online education alternatives.

Another potential solution is encouraging states to prioritize funding for higher education. Indeed, there has been an increased commitment to higher education nationwide, with overall state funding for public higher education increased by 4.5% in 2021, according to Forbes. Similarly, advocates have also proposed providing supplemental financial aid for students living in education deserts, such through grants and scholarships, to help mitigate the financial strain of studying far from home.

Without a doubt, treating a sustainable, long-term plan for eradicating education deserts begins with collaboration between decision makers and higher education institutions. By keeping geography in mind when developing new education policies, such as by using census data when establishing new community colleges, state governments can ensure a more equal distribution of resources.

By looking through inequality through an additional lens – one aware of location-oriented imbalances – decision makers and leaders can design more comprehensive solutions to educational disparities. Step by step, we must transform the country’s educational topography into one green with opportunity and lush with learning.