57 years later, a revolutionary of the Cultural Revolution shares her story

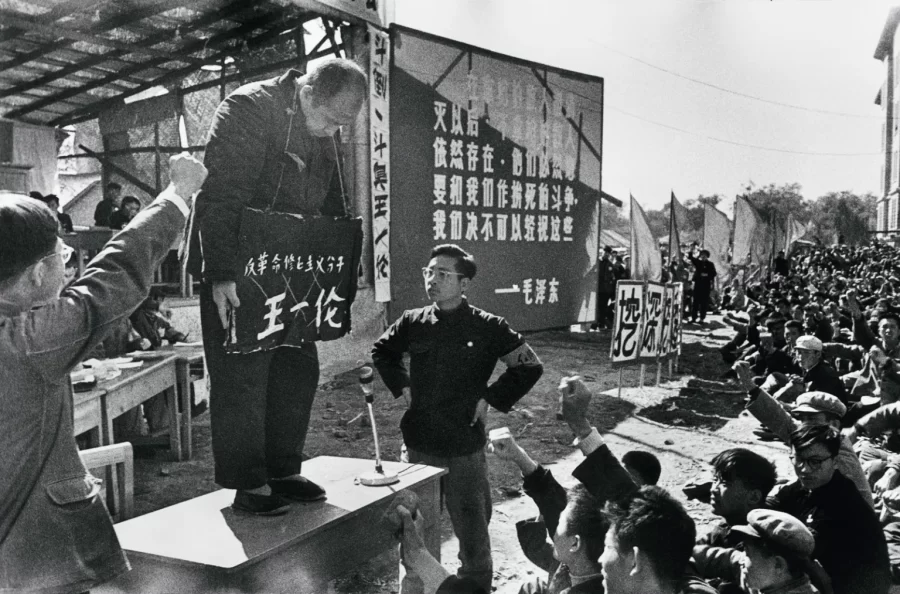

57 years ago, an era of social upheaval, censorship and totalitarianism engulfed the People’s Republic of China. Known today as the Cultural Revolution, this socio-political campaign begun by Chinese Chairman Mao Zedong would continue for ten years. Its aim was to completely revamp Chinese society from its deepest roots, purging all remaining elements of its traditional and capitalist past. Mao created a massive army of ‘Red Guards,’ composed of young Chinese men and women motivated by deep ideological fervor spurred on by overwhelming state-sponsored propaganda to implement his ideals. It was difficult to oppose or disobey this tidal wave of cataclysm—the Cultural Revolution would result in a death toll reaching upwards of a million people with hundreds of thousands of individuals imprisoned for vague crimes and misdemeanors, including the crime of holding an opinion contrary to the state narrative.

For many, this event has long since been relegated to the history textbooks read in our classrooms or the occasional documentary. And yet, right here in Cherry Hill lies a living link to the past. To 57 years ago. To the Cultural Revolution.

Ms. Dai Yun*, 81, lives in her Cherry Hill townhome with her immediate family and her granddaughter attends Cherry Hill East. One would never assume just from the surface that Ms. Yun could ever have had a part in such a momentous and destructive event in history. Yet, decades ago, she took part in the revolution in tandem with the Red Guards, the infamous footsoldiers of Chairman Mao’s overhaul of Chinese society. Though Red Guards consisted officially only of university students, these spirited reformists often implicated the wider public masses with their activities. Ms. Yun was one of these individuals. This past summer, I interviewed Ms. Yun. Assisted in Sino-English translation by her daughter-in-law and granddaughter, Ms. Yun told her story of the past.

The family of Ms. Yun have their roots as farmers in the province of Jiangsu, China. They were not of wealthy or noble lineage. As luck would have it, this allowed them to be spared of the wrath of the Cultural Revolution. And so at the age of 55, Ms. Yun retired from her job as an engineer in the city of Jinan, living with her husband until he unfortunately passed away. Afterwards, Ms. Yun made the choice to move in permanently with her extended family in the United States, where she still resides today.

Ms. Yun describes a Chinese society in 1966 that was gripped between two factions, whom she labels as “the Rebels” and “the Conservatives.” According to her, these factions were engaged in a bitter struggle, with the former aiming to purge perceived capitalist and traditionalist traces in the existing government and the latter trying to conserve the then-current order. The “Rebels” are thus understood as the supporters of Mao’s Revolution. Ms. Yun recalls severe loyalty to her government and its ideals of Communism and she herself took part in the revolution’s activities. Although, Ms. Yun identified personally as a Conservative. Nevertheless, Ms. Yun also characterized the time as one of immense suspicion amongst people. Any connection, real or perceived, to a conservative past could spell doom for an individual and their family. Those who possessed relations abroad, owned land, were intellectuals, or espoused capitalist beliefs were under major threat.

Ms. Yun’s specific role in the struggle consisted of an ordinary participant, along with large groups of fellow communists. She remembers that most of her time was spent writing propaganda posters in favor of the government and spreading them all over the walls and streets of her city. In addition, common occurrences were regular mass meetings of participants and Red Guards with the aim of providing direction for revolutionary activities. Most notably, revolutionaries constantly reiterated Mao’s famed Little Red Book, a collection of quotes and statements by Chairman Mao which formed a guiding pillar of the revolution. Those involved in the Revolution possessed no traditional jobs and played no role in the economy. Rather, individuals and families received government ration tickets for their food, which came from government run and regulated agricultural collectives.

“Workers did not go to work, students did not attend school, farmers did not plant crops. The Red Guard added oil to the fire and increased tensions and conflict.” recalls Ms. Yun. The Chinese public was caught up in strife and uproar. (Incidentally, one of the side effects of the Cultural Revolution was a complete halt to economic development as schools and factories closed).

Ms. Yun also explains a darker side of her role in the Revolution. Red Guards—along with the ordinary public—were frequently employed to keep tabs on other citizens and ensure that all that transpired in civil life remained within the bounds of the state’s ideology. Transgressions could include anything from having pictures of people, to possessing western dresses or high heels. Even curling one’s hair or wearing makeup meant belonging to the bourgeoisie and the hated “Conservatives” in the eyes of the Revolutionaries. Punishments for such crimes included public humiliation (such as being paraded in the street with high heels strung around the perpetrator’s heads), arrest and imprisonment. Even remote suspicion could result in one’s house being stormed and searched by the Red Guards for the thinnest shred of evidence. As stated before, ‘suspects’ open to scrutiny and examination could include anyone who possessed wealth before the rise of the Communists or anyone who had any connections—familial or otherwise—outside of China.

Ms. Yun took part in a number of these home raids as a participant herself. She describes the process of pinpointing a target of suspicion, then arriving at their doorstep with a large group of Red Guards and supporters. Doors were knocked on, and if unanswered, houses were broken into. Searches were conducted in pursuit of three main objects: books and print containing unregulated speech, luxury objects like jewelry or valuables or inheritance with monetary or traditional value. If these items were discovered, punishment was in order. Ms. Yun raided four homes during her time as a revolutionary.

But Dai Yun is not the same person she was 57 years ago. She expresses regret for her actions and does not agree with Mao’s totalitarian policies now that she views her old China with a clear eye. And even back when she was a house raider and propagandist, she had possessed doubts. “I felt bad for the people [we raided],” she said. “But we were afraid to say something or express anger. It was so sad. I don’t think it [was] right to do it. But at the time, the entirety of society was doing it…I followed.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Ms. Yun met many others during the Cultural Revolution, who, like her, realized the immorality of her activities. She describes conversations with her peers behind the scenes where they commiserated their activities and expressed their disillusionment with their ideology. And yet, as Ms. Yun herself stated, the followers felt they had no other recourse.

Oftentimes, the eyewitness stories of such social calamities like the Holocaust or the Cultural Revolution are told from the perspective of survivors, victims, and those on the right side of history. And yet, just as important to notice and recognize are the experiences of those perpetrators, who took part in documented and undocumented repression and injustice. Millions of young people including Ms. Yun took part in Chairman Mao’s cruel Revolution. Why?

It is absolutely crucial in order to better understand the rise of totalitarianism, authoritarianism, or any other such malignant ideology, to examine both sides of the coin, victim and oppressor. It is vital to understand what motivates societies to engage in repression and injustice such as the cultural revolution. It is this understanding that we must bring to the forefront in our historical education. The understanding of how Ms. Yun and the Cultural Revolution ever came to be. To pragmatically glean what brings about atrocity, and the impact of human nature on such societal horrors, illuminates the darkest chapters of human history so that they may be recognized and avoided. We must understand – in order to prevent and prevail.

*Name changed to protect identity