Indigenous in South Jersey

Twenty-six score and ten years ago, Christopher Columbus arrived at a Caribbean Island with ninety men, three ships, and an unparalleled genocidal ambition. Believing he reached the East Indies, Columbus immediately called the indigenous people who greeted him “Indians.” On his first day in the New World, Columbus ordered the seizure of six natives for involuntary servitude.

Columbus’ arrival in the New World marked the beginning of a new journey for Native Americans, characterized by tumult, disease and subjugation. Several explorers followed in Columbus’ footsteps over the next two centuries, conquering indigenous communities and engaging in bloody conflict with tribes across the North American continent. These explorers brought with them foreign diseases — like measles, flu, and smallpox — killing approximately 90 percent of Native Americans.

Native American history has long been sanitized to deify Columbus and appeal to the palates of unaware Americans. We blindly herald Columbus and his succeeding conquistadores for discovering something that was already there hundreds of millenia prior: North America. In fact, Columbus Day itself represents little more than a Eurocentric tale about American history, popularized by novelist Washington Irving in his A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in 1828.

“To help prove that Italians were a part of the American story, Italian Americans latched onto Irving’s version of Columbus, and promoted it like crazy,” said Adam Conover in his educational comedy series Adam Ruins Everything.

But Columbus’ arrival spawned implications far beyond simply “discovering” the North American continent. As nations poured in, racing to conquer this wealth of new land, they set the precedent of racial stratification that’s plagued our nation since centuries before its inception. Spanish colonizers instituted the encomienda system to control native populations, where the colonizers provided education and military protection in exchange for forced labor. With this system came even more tangled social stratification, spawning a new class of Mestizos, or people with both Spanish and native descent. As a result, indigenous blood and access to rights developed an inverse relationship; the more “Indian” you were, the less freedoms you received.

Meanwhile, disease ravaged native populations. The introduction of smallpox to native communities with no immunity led to casualties in staggering numbers. Following the European arrival in 1492, an estimated 55 million indigenous people died.

In the eighteenth century, the French and Indian War marked the culmination of mounting tensions between France and Great Britain to expand their grip over North America. Given the autonomy they still relished under French colonial rule, many Native American tribes held true to their alliances with France during the war. But with a French defeat, the victory for Great Britain (and by proxy, the colonies) entailed a tragic loss for indigenous people — without their most important ally, affected tribes had virtually no protection from colonialism.

As the United States became a sovereign nation post-Revolutionary War, it became even more unrelenting and merciless than Great Britain. The United States fought to eradicate native populations, creating its idealistic “land of the free” (sans indigenous people, of course). When the War of 1812 broke out between Great Britain and the United States, thus, many natives sided with the British out of desperation, grasping at straws for any chance of safeguarding their lands without crushing pressure from the U.S.

But ultimately, a U.S. triumph brought on new legislation that would further suppress native populations. Less than two decades after the War of 1812, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, permitting the president to forcibly relocate natives to unsettled and undesirable land in exchange for land owned by indigenous people within existing state borders. This law, the genesis of the infamous “Trail of Tears” that displaced approximately 60,000 Native Americans, majorly contributed to multifaceted ethnic cleansing; morale deteriorated, tribes perished and cultural practices faded.

Over the past two centuries, despite significant strides in our legal treatment of Native Americans, like the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act and 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act, natives still fight for self-governance, determined to preserve what little land they still possess.

They also fight shocking deficiencies in the American educational system. According to a 2018 survey conducted by the Reclaiming Native Truth project, which aims to shed light on the struggles endured by indigenous people, 40 percent of respondents didn’t know Native Americans still exist.

Indigenous communities clearly don’t receive the proper representation, even with the progress that’s been made to reverse the damage kindled by Columbus’ arrival to North America twenty-six score and ten years ago. It’s our job to change the narrative, helping create an empathetic and civil environment to facilitate conversations about contemporary Native American status.

Do we shape our identities?

Do our cumulative experiences — our formative years, likes and dislikes, friends and families, hobbies and self-expression, cultures and ethnicities — determine who we are?

Or does the federal government?

Thanks to blood quantum laws, the latter seems to be the answer for indigenous communities in America.

Blood quantum laws, imposed by federal and state governments to legally define Native American status, leave indigenous people across the nation in a state of uncertainty and confusion regarding their identity. Upon its inception, the blood quantum system aimed to restrict the citizenship of indigenous populations. The federal government first utilized blood quantum in the allotment period, splitting large chunks of reservation land into individual allotments between 1887 and 1934 under the Dawes Act of 1887.

The vast majority of native tribes set hard cutoffs by percentage of indigenous blood. The Navajo tribe, for example, necessitates 25% “Native blood” for membership. This prohibits certain individuals from membership, regardless of their community involvement or generational ties to their tribe, merely on the basis of their blood composition. During the allotment period, blood quantum provided a convenient method by which the federal government could deprive natives of their land; all they needed to do was cite an inadequate quantity of indigenous blood to strip Native Americans of land ownership.

As governments and tribes use blood quantum to track an individual’s percentage of indigenous blood, they use these arbitrary cutoffs to determine tribal membership eligibility. Beyond dispossession of land and citizenship for Native Americans, the long-term implications of blood quantum laws are far more insidious: slow-burning erasure of indigenous people.

“It was designed to erase us, assimilate us, divide us, and remove us from our communities,” said indigenous actress Elle-Máijá Talifeathers of the blood quantum system in an interview with Now Toronto. “It was a systematically organized way of removing us from nationhood and displacing us.”

Clearly, through the blood quantum system, the federal government has racialized and politicized Native American identities. But this isn’t the first time the American government has weaponized race to stratify Americans. Under Jim Crow laws during the 20th century, the “one-drop rule” imposed by the federal government considered individuals Black if their blood contained even a single drop of Black ancestry. This classification made it easy for the government to ensure every person with any trace of Black lineage would be subjected to discriminatory laws and practices. Similarly, blood quantum requirements benefit the U.S. government in their own twisted way, using a construct of the “Native American race” to inevitably breed indigenous people out of existence. Without any Native Americans, the federal government would no longer be obligated to uphold treaty provisions with tribes.

But the blood quantum system isn’t the only answer. The alternative, “lineal descent,” expands tribal enrollment to more people — the sole eligibility requirement is having ancestors who were members of a tribe. The racialized existence of Native Americans continues to prompt tribes to resort to the lineal descent system, citing the formidability of decreasing populations. While lineal descent poses its own issues, like the deluge of members hoping to join the tribe under looser eligibility requirements, it can be a viable choice for indigenous communities.Ultimately, tribes have the right to sovereignty, and whether they use the blood quantum system depends on their community’s dynamic and needs. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, “Tribes possess all powers of self-government except those relinquished under treaty with the United States,” and the blood quantum system bodes well under certain circumstances for tribes looking to preserve their tight-knit communities.

Nonetheless, Native Americans, unlike every other ethnic group, need to “prove” their identity via tribal enrollment to justify their legal status. With the federal government requiring that indigenous people carry a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood and blood composition dictating indigenous status, who really determines our identities?

The lack of accessibility in finding information on Native American tribes in South Jersey is a significant concern that needs to be addressed. According to the 2020 United States Census, which indicates that only 0.7% of the population identifies as Native American in New Jersey, the townships in South Jersey have even fewer individuals identifying with such a label. East has only 0.10% of the student population identifying as Native American; the same trend is seen in teacher demographics.

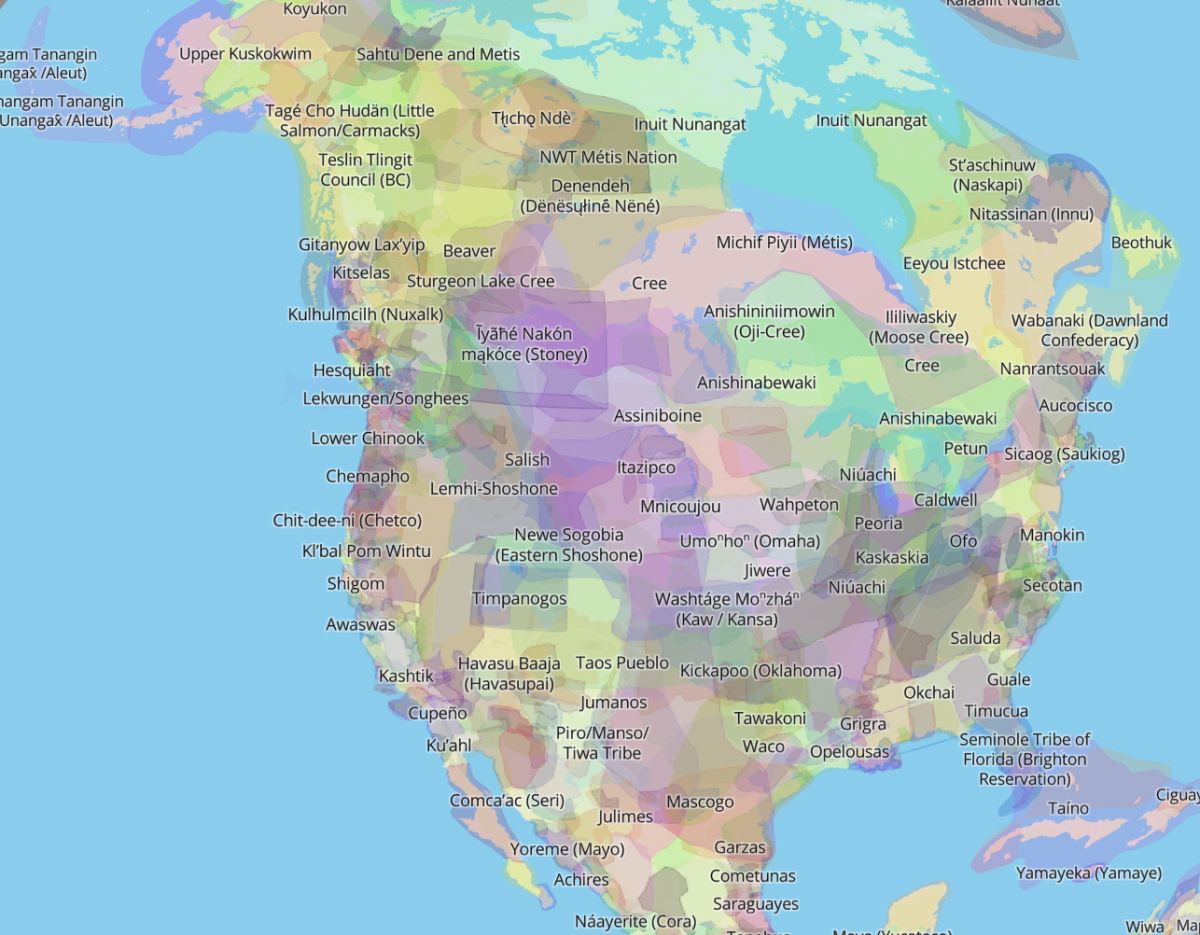

Cherry Hill and the surrounding communities have little to no knowledge, material, or understanding of Native American tribes’ history, culture, and geography. There is a lack of importance given to preserving the history of Indigenous migration and customs in the Township, considering that many townships prior to the 19th century entirely relied on Native American assistance. Despite the substantial Native American population in surrounding communities such as Bridgeport, NJ, the Cherry Hill Township makes little to no effort to acknowledge the history of Native American populations in this region.

To learn more about Native American culture and history, Eastside editors looked to Congressman Donald Norcross’s office to gain insight into tribal paperwork and Indigenous reserves in New Jersey. Eastside also contacted Governor Murphy’s office for a comment regarding Native American reserves, rules, and regulations. However, both offices have not provided Eastside with any information on Native American policy at this time; considering the slow and leisurely approach to such an essential matter, the preservation of Indigenous culture in South Jersey, a more proactive approach would be favorable.

Since 1997, the Secretary of State and the Governor’s office have committed “to promote understanding and knowledge about the history and culture of the American Indian communities of the State.” This commitment comes from the New Jersey Commission for American Indian Affairs, which has nine members, including the Secretary of State, serving ex officio, and eight public members. The public members, recommended by their tribes and organizations and appointed by the Governor, consist of two members from each: Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Indians, Powhatan Renape Indians, Ramapough Lenape Indian Nation, and Inter-Tribal People. Inter-Tribal People refers to who reside in New Jersey, but are members of federally and/or State-recognized tribes in other states.

Eastside editors attempted to call local and State government representatives multiple times for a comment on the issue but received no response. The process of getting in touch with the eight public members of the commission was arduous and unfulfilled; on the Secretary of State’s website, no contact information was listed for the eight public officials representing the tribes. The minimal information written on the matter, the lack of support in questioning, and the navigation to find what little is published are concerning since such information should be made available to the public with ease. The lack of response from Congressman Norcross’s office and Governor Murphy’s office at the time of writing has further aggravated the issue, reinforcing the difficulty for the community to learn about Native American history and culture.

At a time in American discourse when communities struggle to keep the traumatic events of history at the forefront of conversation, it is essential to realize the depth and need for accessible and reliable information.

For more comprehensive Native American coverage, look to Eastside’s January issue