Experiences of East first-generation immigrant students

February 22, 2021

Although there is some disagreement on what being a first-generation immigrant exactly is, it’s generally agreed that a first-generation immigrant is a citizen who has a parent that immigrated to the country that they are citizens of. At Cherry Hill East, there are first-generation immigrant students, who have parents that immigrated from all parts of the world. Being a first-generation immigrant comes with many different challenges. And in this multimedia package, Eastside will investigate the various aspects of life that a first-generation immigrant at East has or continues to go through.

Cherry Hill East students provide answers and perspectives.

What does it mean to be a first-generation student?

To be a first-generation immigrant student means you have at least one parent who is from a foregin country. Being a second-generation immigrant means having grandparents that were immigrants while your parents were born in the United States. Growing up in America and having relative(s) who grew up in a totally different environment changes your perspective on many different aspects such as your culture, religion, and school. These aspects affect students socially, culturally, and academically as their perception of American culture is different from those of students with parents both from America. But what does that truly mean as an East student? Here are a few accounts from Cherry Hill East Students who experience this every day.

STUDENTS:

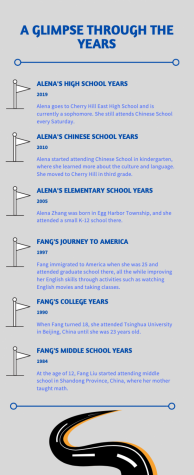

Alena Zhang (’23):

I’ve grown up with the aroma of dumplings and apple pie wafting from the same table. I’ve listened to fragments of Chinese mixed with snippets of English. Perhaps that is what being a first-generation student means – the blending of cultures and bringing out the beautiful parts in each. While I may not be in China and living in Shandong like my parents had, the stories that I hear, the harmony of languages mingling together, and the annual traditions that have originated from so rich a culture have allowed me to experience the vividness of my Chinese and American background in full technicolor.

Yena Son (’22):

For me, being a first-generation immigrant student has been truly a blessing but also extremely confusing at times. Through my experiences, I have been able to learn about the beauty of holding two different cultures and also learn how to appreciate the differences between each one. I will say though, at times I have found myself questioning which culture I truly belong to as an Asian-American but I have realized that I don’t need to categorize myself into one which is the great thing about being a first-generation student. I feel very grateful towards my parents for giving me the opportunity to encounter all the beautiful teaching moments that come with being a child of immigrant parents.

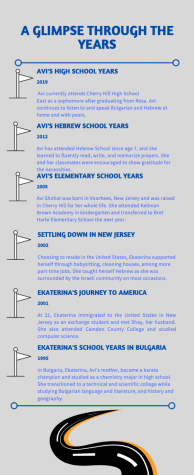

Avi Shohat (’23):

Being a first-generation student signifies a unique message for every individual who proclaims that name. Even so, those who do not proclaim it experience their own circumstances and embody various situations that will only become memories. Those memories do not always prove to be favorable, however, each one reminds the individual of who they chose to be within that moment, who they are in the present, and who they will choose to be in the future. Culturally, religiously, socially, and academically, among more, I learn more about myself every day through the perspectives of my parents and the lenses of my own. My encounters in life have, do, and will vary compared to those of my parents, and although this is true, I cannot imagine who I would be without the foreign characteristics my parents had introduced to me at a young age – music, tradition, food, language, etc. The significance of their upbringings and their incomparable encounters are included in the essentials I hold on to when I feel I forget who I am. I cannot change them as they will forever remain constant. Furthermore, the attributes I possess are those that help me reflect on the qualities that I may improve, or that may be altered. That is what is so beautiful about learning to adjust to a society, through challenges I will not neglect, and in growing into the person I aspire to be. My genetics are beyond my control, and that fact has helped me comprehend the cruciality of acceptance and in learning to be the person that is within the palms of my hands.

Yahel Amsili (’22):

It’s great! Being a part of two cultures in the United States is not uncommon; it is definitely more of an advantage than a disadvantage.

Abigail Nahum (’23):

As a first-generation student I feel like any ordinary student. But it’s cool since me and my dad have very different experiences with school. At schools like Cherry Hill East that have many first-generation students, which makes it feel normal since our school is so diverse.

Mia Ripa (’22):

To me, being second-generation means that I’m able to be thankful for the sacrifices my grandparents and my mom made. My grandparents came to America to have a family and find more opportunities. I’m thankful to my mom because even though she was little when she immigrated, she as an adult feels like she’s more Americanized since she didn’t have a traditional Filipino childhood and in turn wants to make up for years of lost time by connecting more to her roots. I relate to how my mom feels because while she’s full, I’m only half Filipino and I’m white-passing. And I feel weird asking questions to my Filipino friends because I feel like I don’t fit in since my mom and I are both very Americanized, and we didn’t have a similar upbringing in terms of culture as my friends did. In short, while I don’t really think about being second-generation since I feel extremely detached from that side of my heritage, it helps me recognize the sacrifice my grandparents made by leaving their home, and mom to a home she barely got to experience.

Ajuni Oberoi (’24):

Growing up with parents that are immigrants did not seem like it was a big deal when I was younger. Looking back on it now, I can see all the experiences that my parents went through in order to get a better life in America. My mom moved to America from India when she was a freshman in high school, and she quickly had to adapt to a new school and essentially a new life. Knowing now that she had to work extremely hard to get a good education and to have the same experiences as other high school kids makes me want to be able to work harder and continue to grow. My dad came to America from India for his residency after he went to medical school. He came here to do his residency to also further enhance his education in order to become an anesthesiologist. My dad had to work extremely hard to get this residency and then a job here after he immigrated from India. Knowing that I am the daughter of two immigrants, who were able to work hard and build everything they have today from scratch, is incredible and it motivates me to work hard and find the right spot for me in our society.

Rebecca Germaine (’21):

As a first-generation student, I am constantly grateful. Everyday when I come to class and I do my schoolwork, I’m grateful to have the opportunity to receive a good education and have the ability to pursue whatever career interests me. Oftentimes I hear students complaining about school, as I’m sure we all have, but being a first-generation student means I get to share my family’s story with other people and remind them that others around the globe envy the quality of life they currently lead. I work hard in school not only for my future, but to continue on the legacy of my hard working immigrant parents and grandparents.

Nysa Chawla (‘24):

Being a second-generation student, I feel responsible to carry traditions of my family to East. For me, I try to live up to my parents expectations while teaching them new things as well. It means a lot for my family for me to be fully brought up in American and fulfill their American Dream.

My journey as a first-generation immigrant

When I ponder upon the transitions I have undergone, each one, one of the most prominent memories that come to mind is how I struggled to determine which culture and society I belonged to. From my early childhood and attending my first days in a public school, this applied. This applied to a private school for one year, followed by four years in a public elementary school. This only continued for the next three years in a fairly small-scale, public middle school, and where I am today—a public high school from which the outside appears enormous and, yet, somehow undersized when tightly compacted with students charging through the halls before the bell rings.

The difference between culture and society to me is that one remains constant while the other continuously evolves. How one defines “culture” and “society” may contrast with that of my own. Some people, such as myself, view culture as the one-term to summarize the tradition of food, heritage, language, customs, among more, into one term, while others think of culture as society itself—perhaps a community of people that share similar lifestyles, habits, and achievements of art, from music to human intellect. Both terms may be interchanged with one another. However, my definition of culture implies that parts of me, such as my ethnicity and values, will always be incorporated in how I present myself to those around me. On the other hand, society will never remain the same. With advancements in all aspects, from objects to philosophies, today will be different from yesterday, and tomorrow will be different from today. This is simply beyond human control. Although, as each day comes to an end, it is the responsibility of every individual and every community to decide amongst themselves what they believe is best for the future. Their creations change society, whether for the greater good or the worse.

Why do I say this? I felt as if I lived in too very distinctive, dissimilar worlds. Sometimes I still feel like this, but not as often. Each society has its own culture, but each culture does not have its own society. Being a first-born, first-generation American in an Israeli-Bulgarian household, I was tasked with navigating through my life and discovering who I am through attempting to balance my ethnicity and the American environment surrounding me. To this day, I accept guidance from my parents and choose to take their wisdom and experiences to form my individual identity and beliefs. By accepting guidance, I advocate for my needs and learn from their mistakes, leading me to finding a solution to resolve those of my own. But how do I do this when my peers, who are not all first-generation Americans, are influenced by their parents that may or may not have been raised in the same town, let alone the country? I am constantly being told what the “wrong” and “right” choices are to make on a daily basis. This is why it is significant for not only me, but every individual to have their independent values, interests, and philosophies. No one should rely on others to make decisions for them. Everyone has their own truths that may be false to another. It seems complicated, but this idea is undemanding.

Expectations, generally, tend to be prompted by the people that an individual typically surrounds themselves with. The culture is within the people and the society is what the people inhabit. My parents’ expectations are, undoubtedly, lower than the expectations I have for myself. This is not a cruel thing. Rather, I have standards for myself academically or based on my capabilities in all aspects. My parents remain beside me to encourage me to set realistic goals that I can achieve in short-term or long-term time frames. Maybe the expectations I have for myself are higher than those of my parents because I know my strengths, all the while acknowledging my limitations. As they are not me, my parents do not know these traits as well as I do, but they use their culture and society in their countries to assist me in thriving in the society around me. Surely, nevertheless, expectations vary from culture to society, and, especially, the individual themselves. Once again, it is crucial that every individual has their own values.

I cannot count the number of times I have had a friend or classmate come to me and hold forth how their parents are so displeased with their grade, which usually rounded to above an A, that they were punished for an extensive period of time. I could never understand this because my parents do not believe that punishment teaches discipline. They believe that the consequences one will face is how the individual will self-motivate themselves. For instance, when one doesn’t study and receives a poor grade, it will teach one not to neglect studying and instead receive a good grade. This circumstance correlates with my thoughts on stereotypes for how a student should perform based on their ethnicity. I understand that there are cultural factors in what a parent believes are the “proper” ways to raise a child. So, yes, it is not uncommon that two students of the same heritage, separate from one another, have parents that share a similar cultural upbringing that reinforces the idea that culture, race, or heritage raises children using the same methods. This is culture. This is society. What this is not is the individual parent. Think about it: if you are raised in an area where everyone shares the same lifestyle, interests, goals, achievements, and more, would it be that unusual for you to have the same values as those around you? I doubt so. Again, each individual must have their own values.

Moreover, to my parents’ friends who come from countries out of America and to the Americans around me, I used to feel as if I was excluded from both cultures. I understand all three languages—Hebrew, Bulgarian, and English—but I only speak Hebrew and English. This used to seem abnormal to me, given that Bulgarian was the first language I could speak. Consequently, when I used to be around Americans, I would feel as if they perceived me as just the “daughter of foreigners.” Some of them had, and some of them do, which they have made clear to me through their disrespectful comments and remarks. As for those who come from my parents’ countries, I am “too American.” If I do not speak the language fluently or do not have the same values, I am seen through these lenses. This is okay with me, now more than ever. I have accepted the importance of having my own values, and they are concrete in my brain even when others feel it is necessary to tell me where I belong. For me, there is nothing more to do but smile and walk away.

I guarantee anyone that when they are confident and definite in their values, it does not matter who tells them what they think of them. I will never neglect to mention how difficult it can be for anyone and everyone to feel that they are obsolete from a community or be told, constantly, that their values are wrong. As long as people choose to nurture and encourage one another through their values and choose to respect each other for their differences, their values are not dishonorable. Have your own values. Advocate for yourself. As long as you are self-assured that your decisions are made with moral consideration, you will find a place of truth.

Comparing educations between generations

Across counties, states, and countries, school systems vary in terms of grading scales, homework loads, and environments. These gaps, as well as generational differences, may lead to assumptions about how taxing school may be, including misconceptions that parents may have about their child’s workload. Although first-generation children may have parents who learned about factoring and literature in a completely different language, just how similar are their educational experiences?

My mom graduated from high school in China and attended college at Tsinghua University before immigrating to America. While I push myself to do my best, I wondered if my parents experienced the same academic rigor that seems to parallel my peer’s and my school schedules.Although balancing academics and extracurriculars may be difficult, there has always been a fine line between a heavy workload and an unreasonable one. In school, I push myself academically and love to get involved in new clubs and outside activities. However, there is a generational and educational gap in my parents’ schooling in China and mine in America. I have heard that academic excellence is heavily emphasized in China, while in America, there is an emphasis on a more well-rounded education in terms of pursuing interests and hobbies alongside academics.

For my mom, she loved to run track and would often spend hours in the sun, participating in her school team. Since my grandfather worked at the school she went to, she lived there on campus and would walk to school. She tells me of the hours she spent studying for exams and classes.

In China, your admission into colleges rides heavily on one factor: the score on your National Higher Education Entrance Examination (Gaokao). Grueling hours and weeks and months are spent poring over materials in the test, which will ultimately be your ticket into what colleges you are accepted into.

My mother often told me how she wished she had the opportunity to play an instrument, enroll in art classes, and pursue her own hobbies. However, technology and financial limitations prevented her from taking lessons. It is odd to think that the things that have settled into my everyday routine were once her greatest wish, and I feel incredibly grateful for the chance to delve into my interests. I am not saying that my mom lived a hardship-ridden life with no prospect of joy, but I am saying that the opportunities that have been presented to me are far greater than hers during her middle school and high school years.

Although the school systems may be different, our experiences boil down to our yearnings for our interests. When I think of my mother’s school years, which she spent studying intensely in a competitive environment, I feel a sense of awe and gratitude that her work ethic has helped inspire mine.

While we may have been learning in different countries and decades, I think we are both intrinsically connected in our spirit and desires, and they are what continue to push me in school.

As a first-generation immigrant, I felt a cultural divide growing up.

Struggling with cultural identity

As a Korean-American, I am able to experience the best of both cultures. In September, I celebrate Chuseok, which commemorates the harvest by eating certain foods. Whereas in November, I celebrate Thanksgiving by stuffing myself with turkey and mashed potatoes. However, it’s been a cultural struggle as a first generation immigrant because sometimes I just don’t feel like I fit in either side.

Growing up, I went to a predominantly white elementary school in Deptford, NJ, and I don’t remember meeting any other Asian kid at my school. When there weren’t any other Asian kids at my school, kids looked at me weirdly because I looked differently than everyone else. I wanted to fit in badly, and in order to do so, I didn’t want to be any different compared to other kids. As a result, I didn’t want my mom to pack my lunch anymore because she cooked Korean food that smelled “bad” and “fishy,” according to other kids. I even remember telling my mom to not talk to me in Korean when she came to school because my classmates would say insults, like “ching-chong” behind my back. As a kid trying to fit in, I had abandoned a part of who I was, and I slowly drifted away from my Korean roots.

When I was about seven, my family and I went to visit my mom’s relatives. Even in Korea, I didn’t feel like I belonged there. I didn’t know how to speak the language, and I didn’t know much about the culture. When I attended a Korean school near my grandparents’ home, I felt completely out of place, even more so than at Deptford. Everything was just so different. As a confused and naive kid, it felt like a different planet. It was only then when I realized how stuck I was in between the two cultures. I wasn’t Korean enough, but I also wasn’t American enough.

Unlike many other first-generation immigrants that I know, one of my parents lived in America for a long time before I was born. My dad, uncle, and grandparents moved to Philadelphia when my dad was around ten because my grandfather had an assignment there for the South Korean Navy, but they moved back to Korea. When my dad was about to become a sophomore in high school, my dad’s parents decided to move back to the states, but to Cherry Hill instead. He attended Cherry Hill West, and he had to relearn English. Because my dad had been in the country for so long, the barriers that many of my first-generation immigrant friends had to face, like communication and understanding all of the customs and laws here, aren’t as prevalent.

My grandma desperately wanted me to learn Korean, and she taught my sister and I over the weekends when I was much younger. But I hated the lessons, and I saw learning my ancestral language as a burden, not as a gift. Looking back on the past, I regret not learning how to fluently speak Korean. Since I was born my mom has spoken to me in Korean, so I can understand about 90% of Korean. Because of my grandmother’s lessons, I can also read Korean albeit very slowly, and it’s hard for me to translate what the words sound like to what they actually mean. That has been one of the biggest barriers in me fully connecting with my Korean identity.

However, I did feel a connection to Korean culture growing up, and it’s because of my parents that I had and still have that connection. I’ve always attended the same Korean church for most of my life, and it’s thanks to those weekly visits that I felt grounded and a part of a culture, which was bigger than just the food that my mom cooked at home. Additionally, when I was really young, I started doing Kumdo, which is a Korean martial art that’s similar to fencing. Again, like church, I started to feel like I was embracing the roots of my culture and grasping what my cultural identity was.

As a first-generation immigrant, there is definitely that feeling of being in between American and Korean. As I grow up and learn, I become more satisfied with my identity although there is still a way to go in terms of fully understanding my culture.

From the sacrifice and hard work of her parents, Nicole gains their support and motivation.

How I embraced my Goan Culture

Growing up as a first-generation student, I had great difficulty recognizing that embracing my culture is essential to learning about my identity. Without truly understanding my identity, I felt lost and detached because I did not know if I belonged more to my foreign roots or the place I grew up in.

Born and raised in India, my parents traveled to the United States for new opportunities in their professions as my father is an engineer and my mother, a pediatrician. First settling in Dallas, Texas, my parents began to learn American culture through colleagues and even sitcoms, like Silicon Valley, to attempt to understand American humor.

After moving to New Jersey, where I grew up, my parents tried to help me adapt to this new school environment by ensuring that my first language was English instead of Hindi, Portuguese, or Konkani, which are the languages my parents grew up speaking. However, there were unchangeable aspects of my life that made me feel disconnected from other children my age. Both of my parents grew up in Goa, a state in India that was a former Portuguese colony, so they had a different experience than other foreign Indian parents, which then reflected onto me. My family is Catholic, so we did not celebrate Hindu holidays, like Diwali, that are traditionally celebrated in India, simply because they were based on religious values. As a family from Goa, we respect the Hindu traditions by dressing up for the holidays and honoring them with friends, but it is not inherent to our culture. Because of this, I noticed that I did not understand holidays and traditions associated with Indian culture just because I did not hold the same religious values. This caused me to feel detached from my own Indian culture because, in school, the other children of Indian origin celebrated these holidays.

On the other hand, I did not feel accepted on a religious basis either. I went to Catholic teaching after school only to realize that the classes were predominantly white, and throughout elementary and middle school, my family was one of the only colored people in the local church. We stood out, which is not always the best way to assimilate into a new environment.

But then, in middle school, my cousins and family here in New Jersey provided me with a real connection to my culture. Ever since my family moved to New Jersey, we had joined this organization called the Goan Association of New Jersey, which is a group of people here in America who are from Goa. I had never thought much of this organization until my cousins and aunt asked me to participate in a play entirely in Konkani, one of our native languages, to perform for the group. After this event, I then participated in a Portuguese dance with my cousins at another cultural event. I began to embrace my culture more as I attended more cultural events.

As part of the Goan community in New Jersey, I celebrate the Feast of St. Francis Xavier, which takes place in December and is widely celebrated in Goa because the body of St. Xavier is presently in the Basilica of Bom Jesus in Goa, India. At these types of events with other Goans here in New Jersey, we eat cultural and authentic food like steamed rice cakes called sannas, ‘poee,’ which is a Goan bread that has an incredibly fluffy interior, and bebinca, a multi-layered coconut cake for dessert.

Although I initially did not know where I belonged, my journey as a first-generation student changed me and allowed me to identify with my own culture as an American-Goan who enjoys my native traditions and food. In school and my career life, I will continue to embrace and explore my culture, knowing that understanding my roots will lead me to fulfill my own potential better.

My journey of discovering the beauty of my culture

Hi, my name is Alena Zhang. I am Chinese. I used to be ashamed of my culture.

Everyday, my mom lovingly packed me different lunches: dumplings, fried rice, onion pancakes, and every Chinese food imaginable. I loved my lunches. During break-time, I would bring my glass container filled with yummy food and tiptoe to reach the microwave. After heating up my food, a familiar fragrance filled the air and I would breathe it in deeply. It smelled like home, and it reminded me of the street vendors in China.

My first recollection of the harsh reality of what my classmates thought of my food was in kindergarten. As I sat down at the lunch table with my classmates, one of them looked at me with disgust and told me my food smelled and looked disgusting. The limp, fried onion in my rice reminded them of spider legs; the fluffy pork bun reminded them of a disfigured instrument.

When I reflect back on this moment, I still wonder how my younger, five-year old self should have reacted. Should I have told them to back off, to leave me and my food alone?

What I remember is not touching my food at all. I left the mounds of fried rice alone and I sat silently while my classmates snacked on their chips and sipped their juice pouches.

When my stomach grumbled in defiance, I carefully propped up the lid of my food container and tried to cover my lunch with the flap of fabric on my lunchbox, so no one could see my food. Every day after school, my mom would look at my untouched lunch and shake her head. I felt guilty for lying and saying I wasn’t hungry.

Looking back, I realize I should have stood up for myself. In a way, food is culture. A recipe can cross oceans and continents, generations of families, time itself.

At school, I kept my Chinese identity and pupil identity separate. When Chinese New Year came around, my mom and grandpa discussed coming to my class to bring dumplings and make paper lanterns. I held my breath and hoped my mom and grandpa would stop bringing up the topic. I begged and I cried for them not to come, but it was to no avail. They were coming and that was that.

When my grandpa and mother arrived at my class, I expected snarky remarks from my classmates, but there were none. Frankly, I was scared that my classmates would make fun of this tradition like they did to my food. Instead, my classmates begged for more dumplings and compared their paper lanterns. I remember my chest feeling warm and me smiling as they chimed in yelling that they wished they could be part of my family, so they could eat delicious food like dumplings all the time.

What caused the change in attitude, I still don’t know. However, I know this much: I should have never let those initial words insulting my food ever affect my relationship with my culture.

Slowly, I stopped caring about what others thought of my food and culture. In the past, I had believed that my classmates’ disgust for my food was a personal attack on my character and my heritage. But it wasn’t. While the remarks were insulting, I should not have let those sentences loom over my head for so many years. I have learned that my culture, even in something as simple as food, isn’t something that I or anyone should hide.

With Covid-19 affecting not just our school lives, everything is different. I do not take my culture for granted; I am glad that the rich history I come from is not forgotten.

I implore you, do not be ashamed of your heritage. Do not forget the beautiful scenery where your home land is. Do not forget the ethnic food that connects you to your culture. Do not forget the sacrifices your family made to get you here. Do not forget your culture which is ingrained in who you are. It courses through your blood, it makes you, you.

My love for my culture is unshakable. I appreciate the thrumming dances, the noisy villages, the delicate brushstrokes of mountains on silk, and the delicious Chinese food that my mom makes, whether I am in China or America.

My few trips to China still dazzle me. They have shaped me and matured me. I see magnificent statues, hear the crash of stormy waves in the Yellow Sea, and feel the rumble of the Shanghai traffic in my bones.

So please, embrace your culture. Let every part of it wash over you and change you for the better. It welcomes you into its dazzling and unimaginable world.

Building friendships as a first-generation student

Because I attended an elementary school with an Asian population of less than 3%, my immigrant parents often worried if I would fit in with the other students. I firmly remember naturally gravitating towards the other 1 or 2 Asians in my class every year. However, as students enter into high school, specifically those who are first-generation immigrants, they gain more freedom and knowledge on their preferences regarding their friendships. So the question becomes, how exactly does being a first-generation student affect those preferences?

Some students like Inesa Linker (‘23) enjoy hanging out with people who have a different ethnic background than her own.

“I feel that it is easier to get closer to someone when there isn’t as much judgment. With people who have a similar ethnic background, I always feel a level of judgment of whether or not I am Jewish or Ukrainian enough.”

Being a first-generation Ukrainian who does not speak her native language and growing up in a non-religious household, Linker feels that those things make her less connected to her culture. When students with the same ethnicity as her attend synagogue and speak Ukrainian, she can’t help but feel different although they share the same background.

“It ends up being something that separates me rather than something to form a bond over,” Linker said.

While she struggles to share commonalities with people of her own tradition, Linker has learned a lot from being friends with people of different cultures.

“I’ve learned about how they use their culture to shape their lives, and while that knowledge isn’t deep or philosophical, and honestly seems very obvious, it’s really nice to gain that connection with someone.”

Other first-generation immigrant students, such as Ziv Amsili (’22) and Esther Tian (’22), prefer building friendships with students who share similar cultural traditions.

“They tend to understand me better and I feel more comfortable knowing that they can relate to me,” said Tian.

Tian, a first generation Chinese-Korean, values the reassurance that she finds in having a friend who is able to connect with her through culture related experiences. Although she has not faced major struggles with making friends, she has experienced trouble fitting in with people outside of her ethnic bubble due to the challenge of finding things to bond over.

Interestingly, Amsili, who is a first-generation Israeli, shared that she has noticed that many of her friends are first-generation immigrants themselves.

“Maybe because my parents are friends with a lot of Israelis, they also have kids that may be the same age as me, so through our parents, we get to know each other,” Amsili said. In addition to this, especially in her Jewish community, Amsili was able to form friendships through attending the same synagogue as her friends and through their parents who feel more comfortable with those who speak the same language as them.

As for myself, while I have a diverse group of friends, I am definitely more comfortable with my fellow Korean or Asian American friends. Some of my closest bonds have been formed through my Korean church. Nonetheless, that was only possible because there was a Korean church in my area. From personal experience, who I choose to be friends with really depends on my personal interests and the ethnic environment of the area that I live in.

It is safe to say that culture and tradition play a large role in the lives of first-generation immigrant students. But it’s just a matter of one’s distinctive values and beliefs when it comes to building relationships.

Dealing with mental health

Mental health is something many parents aren’t equipped to handle. This line of logic is something that especially applies to immigrant parents. Mental health is an issue that has gained increasing traction in the last couple of years and is something that many families in the U.S. discuss. The difference with first generation families is that these issues are not discussed. Even though they can be coped with and managed with support from a therapist or family members, many immigrant parents see mental health problems as saying that their parenting is inadequate. This is not true, seeing as everyone (including all parents, immigrant or not) deals with some form of mental health trouble.

First-generation families are slow to accept this, partly due to the fact that they grew up in countries where perfection was the standard. Speaking from experience, my mother grew up behind the iron curtain of the Soviet Union. In a teaching job at age 20, she grew up quickly taking many different advanced courses and putting pressure on herself to be a model student and fit the mold of a “perfect Soviet,” which was something ingrained into her life. These expectations were given to my mother by her mother, and then they were given to me by my mother. As a little girl, I was a figure skater. This hobby became something that consumed my mother, and soon enough I felt an exceeding amount of pressure to master each jump and spin as well as compete in high profile competitions. The truth was I didn’t particularly want to keep figure skating-especially not competitively. Young as I was, this took a toll on my mental health, and the way I see myself. Naturally, I am a person who seeks praise from others and watching my mother during and after practice, I became obsessed with getting her and my coach’s approval. To this day, even though I am no longer a skater, I seek her praise and feel that many things I do don’t measure up because they don’t receive the reaction I expect. I know this is a common experience for many first-generation children. High expectations may result in mental health issues.

According to escholarship.org, many studies conducted in higher levels of education show that first-generation students are more likely to experience symptoms of depression, high levels of stress, and lower life satisfaction. These are symptoms that students at the high school level cope with as well. I know very well the distress that I and several of my friends go into before grades are finalized or the night before a test. However, these feelings persist long after the test and can often make one feel isolated and alone because who else feels like waves are constantly crashing over them and they can’t get up so what’s the point? The answer it turns out is many people.

Believe it or not, immigrant parents especially struggle with mental health issue. For example, cambridge.org published an article in 2009 discussing the widely untreated psychological distress recent Soviet immigrants were under, and the US National Library of Medicine published a study in 2015 investigating the use of mental health services by immigrants and found that of the 40 million or so immigrants in America, less than the national average of 13% utilized any services despite an equal or more pressing need for it. One study of Asian and Latino immigrants found that only 6% of immigrants had ever received mental health care, making them 40% less likely than U.S. born participants to access services.

What immigrant parents seem to miss is that discussing and being open about those feelings will often help a student cope with the feelings and help them realize they don’t need to hide their feelings or feel ‘broken’ because of them. Mental health is finally getting the attention that it deserves in America, and more people are realizing its importance in the well-being and health of a person. But the curtain that mental health has hid behind for so many years can not be so easily removed in the eyes of immigrants. That curtain is shrouded in shame, and peeling it back reveals a not so pleasant topic that they are unwilling to embrace. It is so important for first-generation students to embrace the mental health questions that their parents often shy away from. Hopefully, mental health will no longer feel like a taboo and something that needs to be hidden behind a curtain.