New Jersey wildfires

1,400 wildfires were recorded in New Jersey in 2024, according to the New Jersey Forest Fire Service. Most of those fires occurred in November, garnering national attention from many news outlets, mainly in 4 counties: Passaic, Bergen, Burlington, and Ocean.

Compared to the ginormous size of the wildfires in California, most wildfires in New Jersey were relatively small, only burning several hundred acres. One wildfire, though, ravaged much more land. The Jennings Creek Wildfire in West Milford, Passaic County consumed at least 5,000 acres of land; it burned in Passaic County and Orange County in New York simultaneously. New York and New Jersey fire-fighting services extinguished the fire together to expedite the containment process.

On November 15, at 10 a.m. the New Jersey Forest Fire Service communicated via their Twitter that the fire was 90% contained, with at least 2,283 acres burned in New Jersey. This update was the last one communicated publicly.

Other wildfires that drew national attention include the Shotgun Wildfire in Jackson Township in Ocean County, the Cannonball 3 Wildfire in Pompton Lakes in Passaic County, the wildfire in Englewood Cliffs near Palisades Interstate Parkway in Bergen County, the Pheasant Run Wildfire in Glassboro in Gloucester County, and the Bethany Run Wildfire in Burlington and Camden counties. All of these wildfires have been extinguished by this point, as no other updates have been released following the Fire Service’s final updates– meaning nothing significant developed after the final update.

That still does not mean that these wildfires did not cause some destruction. The Shotgun Wildfire burned at least 350 acres, and the Fire Service achieved 90% containment by November 8. The Cannonball 3 Wildfire threatened 55 structures when it first broke out, but none of those structures were evacuated. It burned 181 acres, and the Fire Service achieved 100% containment by November 10. The Englewood Cliffs fire was small, even for the standards of the New Jersey fires, burning 39 acres when the Fire Service gave their last update of 75% containment on November 9. The Pheasant Run Wildfire burned 133 acres and threatened 6 structures when it first broke out. The Fire Service achieved 75% containment by November 8. The Bethany Run Wildfire burned at least 360 acres, and the Fire Service achieved 90% containment by November 8 as well.

The sheer number of wildfires occurring in all parts of the state in November stretched the Fire Service thin. 11,000 acres of land in the Garden State were burned in 2024, part of a devastatingly large number of at least 8,800,000 acres burned nationwide, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. This number is greater than the 10-year average of around 5,600,000 acres.

Some recent wildfires which did not receive as much national attention were a 35-acre Country Club Wildfire in Ocean County, a 40-acre Big Rust Wildfire in Burlington County, and an 11-acre wildfire in Bayville in Ocean County. In December of 2024, all of these fires have been confirmed 100% contained.

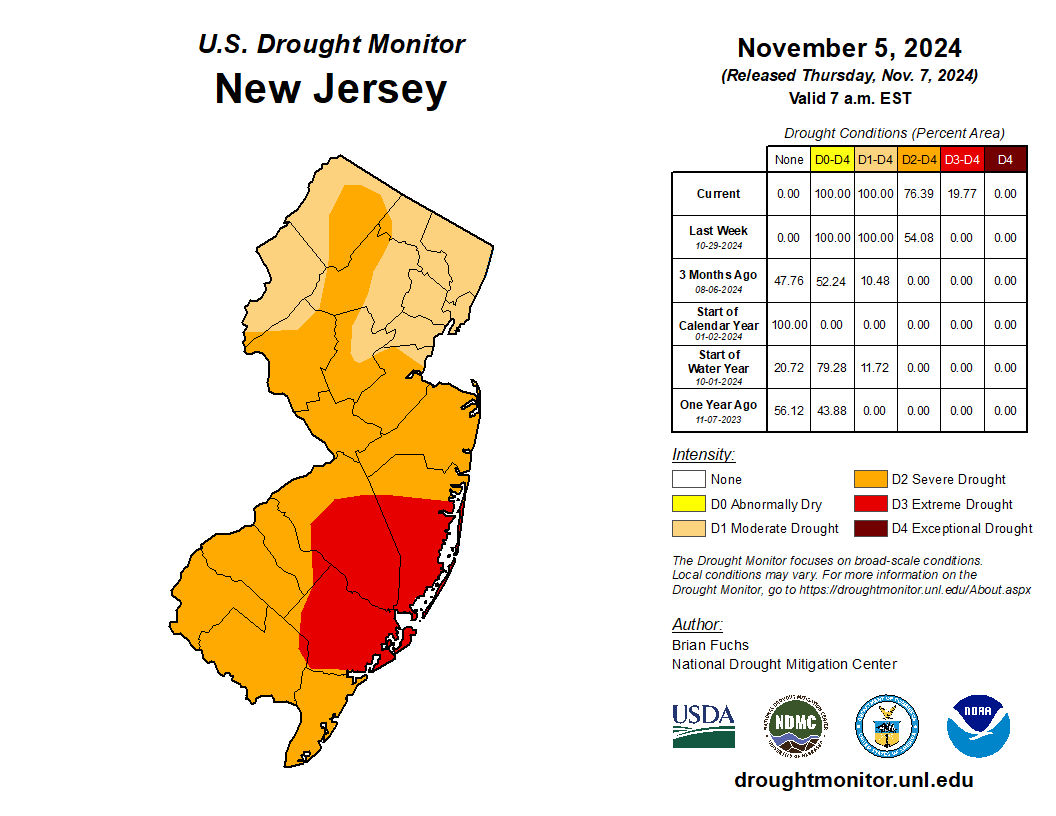

A dry and warm backdrop precipitated the wildfires that sprang up in November 2024 in New Jersey. By the end of October, New Jersey was suffering from moderate to severe droughts. By November 5, the situation worsened to include even extreme droughts in much of Ocean, Burlington, and Atlantic Counties– roughly 19.8% of the state. September was the third driest September on record, with 0.83 inches of rainfall on average; and October was not only the driest October on record but the driest calendar month on record, with a measly 0.02 inches of rainfall on average. For comparison, the next driest month ever was October in 1963 with 0.25 inches of average rainfall. The September-October pair was the driest bimonthly period on record as well. Towns all throughout New Jersey struggled to measure precipitation, and the Rutgers New Jersey Weather Network called October “bone dry”.

The average temperature (in Fahrenheit) was 2.1° higher than normal at 57.5°, with warmer highs and colder lows in October. The average high was 5.1° above normal at 70.9°. The range of temperatures between lows and highs throughout New Jersey was 26.7° on average, which is alarmingly wide according to the Rutgers Weather Network. Temperatures would continue to be higher than normal in November as well with an average temperature of 49.1°, 4° above normal. The drought that the state experienced for most of September and throughout October would finally cease in the latter half of November when precipitation came to most of the state on November 10 and 11, with more substantial precipitation coming on November 20.

Higher temperatures and extreme lack of rainfall are the perfect prerequisites for wildfires. The common fuel, grasses and trees, become more flammable. They die out on large scales, then soil dries out, streamflow and groundwater decrease, etc. If the fuel becomes more flammable, then the wildfire has more potential to affect more acreage and cause more disaster. All it takes is one ignition.

New Jersey’s climate was a driving factor in the wildfires, but one other now infamous cause was arson. The Shotgun Wildfire in Jackson Township was ignited by the firing of a shotgun round– which is why the fire is called ‘Shotgun’ in the first place. The man behind it was Richard Shashaty, a 37-year-old who illegally fired Dragons Breath ammunition, igniting the dry environment it hit. Dragons Breath ammunition is only used for entertainment purposes. It is meant to simulate the effects of a flamethrower, but when not used in a controlled environment can easily cause fires. The effect is usually created when the magnesium pellets or powder inside ignite when in contact with oxygen in the air.

From arson to exceptionally arid conditions, the state had enough to spark the over 500 wildfires in October and November.

The New Jersey Forest Fire Service is an agency within the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. They are responsible for protecting life, property, and the state’s natural resources from wildfires. William Love, the Assistant Division Forest Fire Warden in the New Jersey Forest Fire Service, gives his perspective on wildfires.

Love’s role is to supervise fire safety arrangements to prevent a fire from endangering the health and safety of occupants. Love is assigned to the Trenton headquarters of the service; however, this does not limit the areas he supervises. He has been all over the U.S., from California, to Alaska, and to Montana.

Many people in New Jersey have noticed an increase in wildfires during the fall of 2024, which the New Jersey Forest Fire Service observed as well. Love said that this is largely due to the drought season that has been happening in New Jersey. Drought conditions can dry out vegetation, causing plants to become more flammable. Drought can also increase the rate at which a fire can spread. Wildfires such as Jennings Creek fire, which was burning on the border of New York and New Jersey, have managed to spread quickly, reaching 5,000 acres, due to the prolonged drought.

Although the drought has caused more fires than usual, most fires do occur during the fall and the spring in New Jersey. They mostly arise between March and April. This is due to the warmer weather and stronger winds that occur during spring.

With this in mind, people may assume that wildfires are predictable, but that is not always the case.

“Weather always changes,” said Love. “You can never be too sure.”

Under the influence of climate change, temperatures randomly rise and fall, and winds suddenly get stronger making it hard to assume when a forest fire may occur. Still, the New Jersey Forest Fire Service is prepared to handle a wildfire whenever they occur. They have people on the line if they ever need more assistance and always have tanks of water ready.

Weather is not the only factor that plays a role in how fast a fire can spread. Population density can also influence how quickly a fire spreads.

“New Jersey is a highly dense area, especially compared to New York and Philadelphia,” said Love.

Houses in close proximity to each other can cause fires to spread quickly and become harder to contain.

“That’s why the fires in California [happened], the houses were close by, and it spread quickly,” said Love.

Although the increase of fires during the fall of 2024 was due to the drought conditions, the causes of the fires itself are usually not weather related.

“99% of fires are caused by humans, only 1% are caused by lightning,” said Love.

Wildfires can occur from campfires and house fires, but there have been many fires caused by arson.

“I had to arrest people before,” said Love, “[around] 7 people.”

With this in mind, Love said that the best way for communities to be safe from fires is to prevent fires from happening, such as being careful while camping or in the house. If a fire is caused by arson, advisors usually put out a red flag warning to signal that there is a fire nearby. This gives people time to either stay safe in their homes or evacuate the area.

Unfortunately, some people may not take these warnings seriously if the fires are small.

“You have to remember that even small fires can be dangerous,” said Love.

Small house fires can spread quickly, causing danger to the residents in the home and neighbors as well.

To contain small fires, firefighters use direct attack tactics. They drive into the woods with their specialized brush trucks that are armored. These trucks can push trees in their way up to 4 inches in diameter to get to the edge of the fire. Firefighters then drive around the perimeter of the fire, spraying water from a hose line to extinguish it. They then follow up with a bulldozer that puts a trench into mineral soil around the fire to prevent escape. Firefighters may also employ helicopters that can drop 300 gallons at a time or aircraft that can drop 800 gallons of water.

If the fire is of significant size or is burning too rapidly for a safe direct attack, they attack the fire indirectly. This is accomplished by lighting a backfire along a road well in advance of the main body of fire and starving it of fuel to continue to burn.

Despite these strategic efforts, it may take a long time for a fire to be completely extinguished.

“A fire started on the Fourth of July, you know, it didn’t end until [December]… It burned for 5 months,” said Love.

It is important for residents, especially in areas that have had wildfires, to be alert on updates. To make sure a fire is completely extinguished, firefighters continuously go back to the affected area to gradually contain more of the fire, which can take up to months.

As seen from the amount of time and effort they put into their work, firefighters from the New Jersey Forest Fire Service are deeply committed to protecting the community from wildfires. Their unwavering dedication and hard work should not go unnoticed.

“We do the best that we can,” said Love.

New Jersey, the Garden state, is not the state that comes to mind for most people when thinking about the continuous occurrence of wildfires. However, throughout the last couple hundred years, wildfires have played a large role in the New Jersey environment.

New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the United States (excluding Washington, D.C.), while also holding the Pine Barrens, also known as the Pinelands, which spreads throughout 7 counties in New Jersey. The Pine Barrens cover over one million acres of land that have highly flammable trees, filled with combustible pitch pines and scrub oak trees. When June 12, 1755, came along, the Pine Barrens encountered a 30-mile-long fire.

For most of the 19th century, it was not uncommon for almost 1,000,000 acres (40,000 hectares) to burn in the Pine Barrens annually, according to R.T. Foremen’s and R.E. Roerner’s study in the Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. In 1838, on September 7, another fire broke out, this time in Burlington and Monmouth Counties, where there were 179,200 acres that encountered property damage and loss.

Starting in 1899, there was a recognized need for forest fire control. Soon after, in 1906, the New Jersey Forest Fire Service, also known as the NJFFS, law was established.

According to nj.gov, this law forbids “setting fire to any forest, brush or grassland, or tidal marsh except as exempted; setting fire to brush, litter or debris without the written permission of a fire warden; having any fire by which property may be endangered without maintaining a careful and competent watch.”

With this law, 3.15 million acres of public and private lands statewide are required to be protected, covering the north, south, and central areas of New Jersey. Forest fire wardens are assigned to districts, and the warden is responsible for recruiting and training fire crews, while also training firemen for additional jobs. The crew also had the help of the plow/dozer units, aircraft, and specialized equipment.

However, the wildfires naturally did not stop occurring in the state of New Jersey. Throughout the 1900s there were multiple disastrous wildfires. In May of 1930, a wildfire spread in the pines of Ocean County, notably striking the towns of Tuckerton, as reported by the New Jersey Courier, and also Forked River. The number of acres burned in this fire ranged anywhere from 60,000 to 200,000. One wildfire often credited as being the worst was a series of 37 major fires in 1963. The 37 major fires burned 193,000 acres of land, 186 homes, and 197 buildings, killing a total of seven people.

Moving forward to more present-day wildfires, due to a long drought in New Jersey, the wildfire season was longer than expected. Because of the dryness, low humidity, and high winds, on April 11, 2023, a wildfire burned 4,000 acres of land in Manchester Township, Ocean County. This wildfire was known as Jimmy’s Waterhole wildfire, which was the largest wildfire seen in that specific area since the 1990s.

With droughts being the cause of some wildfires in 2023, the problem certainly continued into October and November. However, one of the first of many wildfires caused in November of 2024 began because of something different.

According to CBS News, “The fire [in Jackson Township] was ignited by magnesium shards of a Dragons Breath 12-gauge shotgun round, which ignited combustibles on the berm of the shooting range, prosecutors say.”

As mentioned in previous stories, the wildfire spread over 350 acres of land and the man who started this fire was charged with arson.

Additionally, there were two other fires that started a day after, on November 7, 2024, with one being the Pheasant Run Wildfire, in Glassboro. This wildfire did not threaten any structures but covered 133 acres of land.

At the same time, a wildfire in Evesham broke out that forced evacuations because it threatened about 100 homes, as it was in the woods behind many family houses. This wildfire was known as the Bethany Run Wildfire and burned 360 acres of land.

The history of wildfires in New Jersey leading up to present day represents the ongoing threat of wildfires in the Garden State. Whether the fires are started by human or poor weather conditions, the continuous wildfires highlight this issue in New Jersey. Although wildfires are not the most well known in New Jersey, they have always and will continue to play a big role in the state’s past, present, and future.

Playing a game of Jenga, you focus on the tower of wooden blocks and carefully weigh your options. After all, one wrong move could send the entire structure tumbling. Do you opt for a risky turn by removing a block from the middle, or do you play it safe by taking one from the top? Pulling a block from the middle, you feel the structure wobble slightly, and, as you replace the block, you notice that your hand begins to tremble. Indeed, one wrong choice — one failure to commit fully to your strategy — can lead to catastrophic consequences.

Such is the case with efforts to prevent destructive wildfires. The methods we employ to protect our forests and communities are only as strong as our commitment to implementing them. Several efforts to conserve against wildfires, in tandem with recent methods to prevent them, should and have been used amid increasing drought conditions and rising global temperatures.

Ironically, one of the most effective traditional prevention methods, controlled burns, also known as the prescribed fire strategy, involves intentionally setting low-intensity fires to clear out dry vegetation. Strategically burning areas with excess underbrush and dead materials establishes a buffer zone, minimizing exposure to uncontrollable blazes. In fact, federal land management agencies conduct 4,000 to 5,000 prescribed burns annually and have more than a 99% success rate, according to the U.S. Forest Service. Forest thinning, another prevention method, reduces tree density thus limiting the amount of flammable materials available to fuel fires. Along with decreasing the likelihood of a future wildfire, these practices simultaneously help keep ecosystems healthy by destroying invasive plants and opening up space for new growth. Similarly, firebreaks, cleared strips of land designed to stop or slow the spread of wildfires into vulnerable areas of infrastructure- if properly maintained- can reduce wildfire spread by around 80%. Additionally, grazing, where livestock is used to naturally remove dry vegetation, offers an eco-friendly way to manage fire-prone landscapes.

On top of the aforementioned traditional methods, recent innovations have emerged to assist in wildfire prevention. One such approach is the reliance on advanced remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and drones, to monitor forest health in real time which helps pinpoint possible fire hazards at an early phase. Furthermore, AI-based modeling anticipates areas of high risk for flames spreading by analyzing weather patterns and vegetation conditions. Applied to homes, vegetation and infrastructure used for temporary protective barriers, fire-retardant gels and sprays are other recent innovations that can at least slow down the spread of flames.

Of course, traditional methods and innovations are necessary to prevent wildfires, but individual actions can also prove extremely beneficial. Humans can, for example, help remove dry debris in local areas or notify authorities of unauthorized burning. Moreover, educating others — and, of course, yourself — about fire safety and the importance of having responsible outdoor practices, whether extinguishing campfires or adhering to local burn bans, can strengthen community efforts in wildfire prevention. After all, 99% of fires are caused by humans, so increased awareness can save the hassle of being overly dependent on these traditional methods and recent advances that, though reliable, can only do so much in the long run.

Similar to how each move in a game of Jenga can affect the tower’s stability, every preventative measure taken — through traditional methods, recent innovations and human actions — can save our biosphere. But it takes all of us.

We went out to a locally affected area in Evesham to see how it looks now. See below for some of the pictures taken by Mika Bhaskaran (’27). Photos were taken in January 2025.