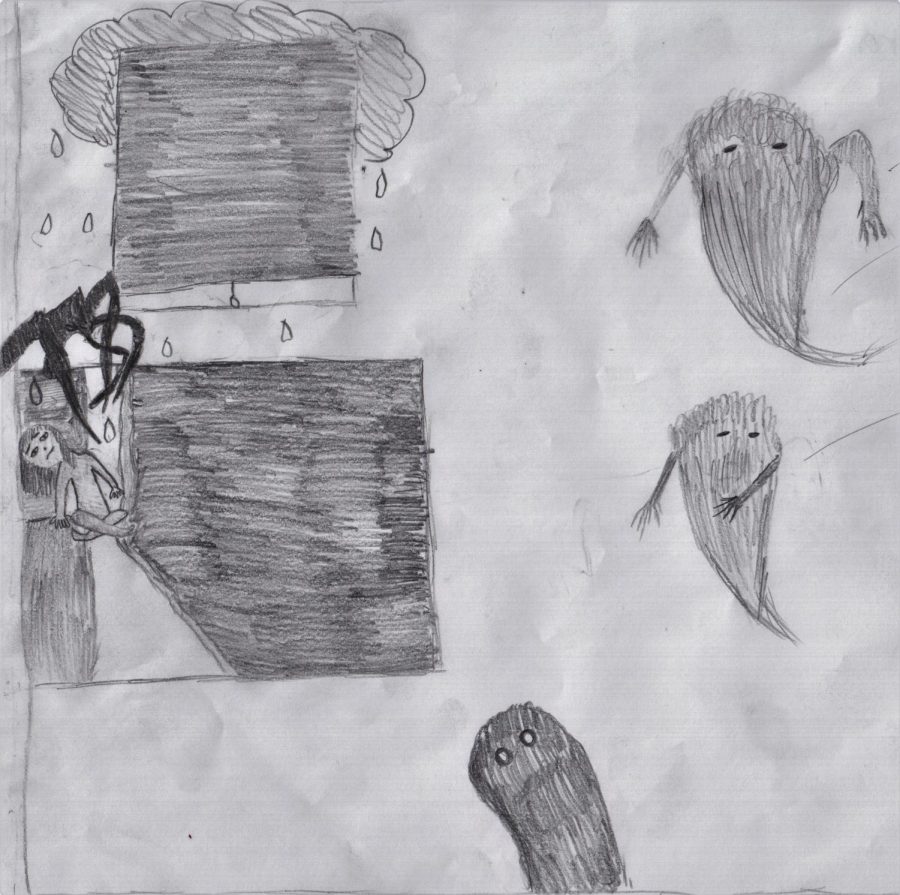

Depression

Underwater – Anonymous Senior (’19)

I am drowning when I bury my face in the water. My breathing decreases as I slowly close my eyes.

My hands shake and my fingertips tingle. The warm water does not tame my body’s chill. I try to deduce a simple plan to start breathing again, but I stop. I am too tired. After a minute, I feel dizzy. I tell myself to bring my head up, but the water pulls me in deeper. Deeper and deeper I sink, and the farther I go the weaker I feel. The seconds that pass feel like days, but the feeling of waiting is more than I have felt in a while. I can tell that I am losing consciousness, but my worries are too strong, and I cannot fight them any longer. I feel my knees lock in place when my body starts to crumble. The little fight left in me keeps me standing.

Water rushes from the faucet and shoots at my body with incredible force. Every drop washes a wound, but every wound reforms almost immediately. A million invisible scars cover my tired body, and the pain grows when I know no one sees them. I cannot feel physical pain, only a kind of indescribable exhaustion that breaks me down in its own horrible, concealed way.

When I lay my head against the wall, a picture flashes in my mind.

It is the day my brother was born. His small hands gripped onto my mother’s as she cried. “He’s just so beautiful,” she whispered as she kissed his head. Then, I remember the day we almost lost him. I remember his shaking and his face turning blue. My mother ran up to the closest house to find someone to call for an ambulance. I waited in the car with no idea of what to do. Then she ran out of the house and pressed her face against the car window. Her look of terror shocked me. It was the look of a woman afraid to lose her child, the look of a woman who could not take another heartbreak.

I cannot give her another heartbreak.

I force my head out of the water and air rushes into my lungs. My body replenishes itself as I regain energy. I grab the closest towel to me and sprint down the steps. I walk up to my mother and through tears and unsteady breaths finally say, “Please help me. I don’t want to die.”

Anxiety and depression are two of the biggest issues I faced. My mental health quickly shot to the top of my list of priorities after I considered taking my own life. I visited a crisis center and attended therapy sessions because I realized how valuable a healthy mind is. I hope that anyone struggling with mental health finds the strength to fight for a little longer and to ask for help. Admitting that I needed help was the best decision I ever made, and I hope others who feel like I did reach out for assistance. Every person deserves to live, and every life is worth living.

Helping Myself – Anonymous Senior (’19)

I was aware of the realities of the world as a small child; painful memories from my late childhood made me develop a hatred for life. My sadness grew into depression in eighth grade. I stopped enjoying what had previously made me smile. My mother knew how I felt, but at the time she was against antidepressants. She sent me to several therapists, but I disliked all of them.

Months later, I ended up in the doctor’s office because I had trouble eating. My stomach was constantly upset and I would get physically sick. The doctors tested me for many viruses and diseases, but all the tests came out negative. They finally concluded that it was my mind that had made me sick. My mother no longer had a choice but to allow me to take antidepressants.

My depression worsened in ninth grade. I knew everyone, yet I was very lonely and spent lunchtime sitting in a bathroom stall, writing. That’s how I coped in a healthy way. However, most of my coping mechanisms were unhealthy. I began cutting my arms up in ninth grade. In tenth grade, I started developing dangerous drinking habits. I drank hard liquor frequently while alone in my room.

I did attempt suicide a few times. I was having hallucinations at that time. I would often see scary people that would cause me to break down crying and run into my mother’s room. Eventually, I ended up in the emergency room at the end of sophomore year. I waited to be moved to a psychiatric unit for three days. During those three days, I met some amazing people and I watched a woman die right in front of me.

I also met a lot of people when I was in the psychiatric hospital. I was trapped in a small room with bars over the windows. The walls had “hell” and “get out of here” carved into them. The nurses treated us like animals and made us feel like we were in jail. They did not help a single bit. If I can compare myself to a dying fish, it was like they threw me on dry land and expected me to live. If anyone tried to run or do something they weren’t supposed to, they would tie them down or inject them with what they called “booty juice” that was meant to calm people down. I had to watch this a couple times. The food was terrible and made me almost throw up. My parents weren’t allowed to bring food. My nana had to sneak in a muffin and I had to eat it over the toilet in the bathroom. Like I said, writing is my coping mechanism, yet they wouldn’t allow me to write because I could potentially harm myself with a pencil. They watched us when we slept. My arms were covered in nail marks from digging in so hard when I was scared.

I begged my parents to get me out of there. I told them it was making me worse. But it wasn’t their choice; the doctor ultimately decides when patients are discharged. I pretended like I had a life-changing experience in the hospital, and she let me out. Along with depression and anxiety, she diagnosed me with PTSD and panic disorder.

During the spring and summer after I was an inpatient, I completed an outpatient program for eight hours a day. It did not help too much, but at least it did not make matters worse. I went through junior year, and I still felt terrible. I threw up a lot when I was sad or anxious, and it got to a point where I could not take it anymore, and I began to be homeschooled, or “homebound” as they called it. Tutors came to my house for almost two months. I got texts a month in asking me, “When is the test?” and “Can you send me the homework?” No one really noticed I was gone. I had many friends and people I talked to at the time, but there was no one close to me and no one my age to support me.

My mother made me go back to school two months later. I faced extreme difficulty, especially for the first couple weeks. The only reason I went back to school is because my mother fought for me to be accepted into a program at East that no one really knows about — it’s like in-school therapy. Since I’ve joined that program, school has been slightly easier.

At that time, I took a genetic test to find the best medication for me. I had previously been on many different medications that either made me fat or numb or just didn’t work for me. It took me around six therapists and four psychiatrists to finally find the right ones.

Along the way, there have been many people that helped me deal with life, but mainly, I have helped myself. I want to get better, and I try extremely hard to better myself and force myself out of bed. It’s weird because everyone knows me as a very smiley, outgoing person, but really, I’m mostly introverted and my talking a lot is because I’m so anxious and I need to channel my energy. I continue to go to a psychologist and psychiatrist. I’m not cured now. But I’m better. And that’s enough for me.

On the Highway – Anonymous Senior (’19)

I am not afraid to drive on the highway at night. The uncertainty is petrifying to most, forcing us into a truly vulnerable point, completely aware of the world around us while simultaneously and almost paradoxically lost in worlds of our own. We become hyperconscious of what is going on in the minds of others. We understand why we are on that road, but why are they? Where are they going at 85 miles per hour in their beat-up 1999 Honda Accord? What force of nature put the both of us on this strange path, surrounded by vacant Motel 6’s with broken vending machines? How many stories could I find inside of the brains of my fellow travelers?

As if the setting alone wasn’t enough to inspire creativity — the rich red tail lights blending together against a starless navy blue sky, the gentle hum of the engine’s motor, the subtle scent of dew collecting on the road, the comfort each of those details bring. I wonder if anyone else is romanticizing this moment as I am. Maybe someone is, or maybe they are going over their plans for tomorrow, or wondering if they fed their cat this morning, or hoping that their favorite person will call back; small, seemingly innocuous thoughts. What a person thinks about when their mind is left to wander, when there are no distractions, when they are on that vacuum of a highway, isolated and also intrinsically connected, is so incredibly telling.

I like peering into the minutia of the human condition, but I forget to reflect internally. Where does my mind go when I drive that length of pavement? What does that say about me? I ponder the yearning to understand those I haven’t yet met, my curious eyes wandering over the other drivers, searching for any sort of discernible personality trait. During my observations, however, there is one emotion so visible and so ubiquitous that it becomes hard to ignore: fear. The others don’t share my perspective, my point of view. I’m not scared. I’m not scared, in this moment or ever, because I have faced death. I have looked right into her hypnotizing eyes and almost gave into her soft embrace, eager to find the solace she promised. I have gotten to that point, and I have pulled myself back out. That pitch black stretch of road before me will never compare to my struggle with that beautiful demon.

The diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder didn’t sound like a death sentence. But it felt like one. I have been battling my brain since before I can remember, and for quite some time, I lost. I missed a combined total of around nine months of school due to the illnesses that stole my youth. Though it was absolute torture, I am thankful for my experiences. I know my maturity and general understanding of the world is unmatched for someone my age. Being a writer, I reap the benefits of this; I am able to create authentic stories and depict realistic characters. That’s not to say that my struggles can be compartmentalized into one neat pile, but the moral is: I’m still alive. I am stable. I am positive and motivated, and I feel like myself again. It doesn’t sound like a feat, I know — seventeen years, in regards to most living things, excluding gnats and flies, is a relatively small amount of time to spend on this earth. But I am proud of myself; I never expected to make it past high school, let alone get to look forward to college.

That’s why I’m so curious about the lives of others. Because I spent too many of those seventeen years wanting to end my own.

Livin’ the Dream – Anonymous Teacher

I teach Chemistry and Physics here at East. When I read that Eastside wanted teacher input on a project about mental health, I have to admit I felt a bit of a pit in my stomach. I feel it much more now as I’m writing this, but I feel an obligation as a teacher and a scientist to share my experience. I hope someone will read it and be motivated to take the next step, to ask for help and to make themselves the healthiest and most fulfilled people they can possibly become.

When I was young, as far back as I can remember probably, I had a lot of trouble talking to people about things. I’m naturally shy and introverted anyway, and everyone around me would just chalk it up to that. I couldn’t really talk about my feelings, and when I did I was usually told that I was just being too sensitive, or that I was overreacting. So I developed a habit of just keeping everything inside and putting on a happy face. That happy face, the ability not to show people what I’m really feeling, is something with which I think a lot of people may be able to relate.

That habit didn’t hurt me too much at first. I was a talented student and earned good grades throughout most of high school and college, so nobody really gave me a hard time about it. After college, I decided to go to graduate school, and now there’s a decision I should have talked to somebody about. But since I didn’t really talk to anybody about anything, I was unknowingly starting myself on a slow spiral into a very dark depression.

In grad school, I found my talents in the classroom were either inadequate or useless. Where B’s had been disappointments before, they were now what I got when I put all my effort and focus into my classes. My research made me feel like I was dumped into the middle of the ocean and asked to learn to swim. I was surrounded by all of this information, and only very small parts of it were useful to me. I had no idea how to start. I tried asking for help from professors and colleagues alike, but I felt like we were speaking different languages.

I worked on my research in a lab that had very little funding, and my endeavors were largely unsuccessful. It took me seven years to realize just how unsuccessful that was, and by then my lab had run out of funding, my research advisor had left the university and moved back home and I was broke and back living with family. I spent my days pretending I was trying to write a thesis the university might accept, but really I was browsing Youtube, Reddit or other less reputable corners of the internet.

More than that, though, I spent those days, maybe nine months of them, berating myself for my failure. Each day was another step into a dark pit where I was a broken piece of humanity, where I didn’t believe that I was worth anything to anybody. I believed the world would be better off without me, that I was a complete failure and a burden on the people I loved. I think the only thing that held me back from killing myself was how I knew it would make my family feel. I look back at that part of my life and I am amazed that I am still alive today.

Eventually, some of my family sat me down and said, “You can either finish your thesis or not, but you need to have a job and earn some money while you’re doing it.” They suggested substitute teaching, as subs are always in demand and I had more than enough credits to do that. So I filled out the paperwork and became a substitute teacher.

I will never forget the first time I walked back into a classroom. It was Mrs. Sciortino’s third grade class. I will never forget the smells, from the pencils and paper to the Expo markers and industrial cleaner. I will never forget how it looked, those little desks with name tags on them, the various charts on the walls, the carpet that was also a global map and the library in the back of the room. And I’ll never forget the sounds of that day, the chatter of the children and all the wonder in their voices as they talked about literally anything under the sun.

That day is what turned me around. When I walked into that classroom I felt like I had finally come home. When I walked out, exhausted, I knew I could die a happy man if I could do that again every school day for the rest of my life. It was very soon when the only question I had was what to teach, instead of if. I worked there for two years while I figured that out and then while I worked on my teaching certification. In that time, I subbed for just about every teacher in that school. One of my favorite parts was getting to know hundreds of students whose curiosity and wonder were contagious. The best part, though, was that school felt like a place I could be my true self again. The happy face I’d learned to wear so well was no longer a mask but my real, actual face.

I am absurdly lucky to have had this happen to me. In the darkest part of my suicidal depression, I found something that made me feel worthwhile again, and I did this without any professional help. How many people make it through to the other side of that?

The reality is that I should have been seeing someone, a professional therapist of some sort, since I was a young man. It has taken all these years, and all those ups and downs, for me to finally see the truth of that matter. So, dear reader, I make a pledge to you: I am going to get help from a mental health professional. Even though I have made it through what I hope is the darkest part of my life, it doesn’t mean I don’t need help anymore. There are always ways we can make ourselves better, and this is a step I know I need to take to do that.

If you feel like you need the same kind of help, I urge you to reach out to someone who can help you. It may be a friend, a family member, a teacher or a mental health professional. We all need people to talk to, especially about the things we feel like we can’t talk to anybody about.

I’ll close by saying that when I was at my darkest point, my dream was simply that I would find a way to be useful to the world and to feel good about doing it. So if you see me in the hallway and ask me how I’m doing, I’m not lying when I say I’m livin’ the dream.