Exploring racial health inequity in healthcare

April 3, 2023

Racism is a system that selects opportunities and values people based on their appearance or skin color. It consists of institutions, rules, behaviors, and conventions. The construct leads to situations where some people are unfairly discriminated against. Racism, both interpersonal and structural, has a detrimental impact on millions of people’s mental and physical health, preventing them from reaching their optimum degree of health and, as a result, impacting the health of our country. A rising corpus of data demonstrates that communities of color have suffered significantly due to prolonged racism in the United States. The effects are widespread and deeply ingrained in our society — affecting where one lives, learns, works, worships, and plays, creating inequities in access to various social and economic benefits — such as housing, education, wealth, and employment.

Historical backdrop of mistreatment in healthcare settings

Addressing the key components

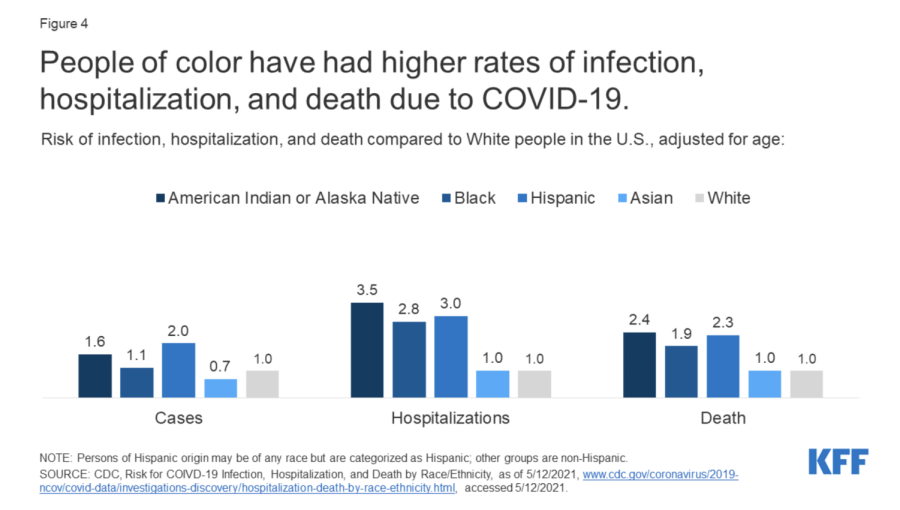

People of color have had higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and death due to COVID-19.

Public health influences the population’s welfare and protects the community from diseases creating a safe environment for all. However, minority groups are negatively affected as they have limited access to healthcare compared to their white counterparts in the United States. The conditions people of color face refer to social determinants of health, which play vital roles in health inequities and result in poor health outcomes.

Healthcare disparities are often viewed through the lens of race.

Discriminatory practices in healthcare settings negatively impact mental and physical health, creating barriers to healthcare for many individuals. Because minorities are not receiving the highest level of treatment, their health outcomes will be much poorer than that of white individuals. Generally, insurance companies are responsible for providing comprehensive coverage.

For most individuals, insurance is provided through a place of employment. As a result of high unemployment rates among minority populations, many individuals are often left without insurance or a more limited policy. Systematic racism that contributes to economic instability, access to education, and physical environment drives health inequity.

According to Paula Braveman, a University of California Berkley researcher, health equity is when “all people have the opportunity to attain their full health potential, and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of their social position or other socially determined circumstance.”

After the Covid-19 pandemic, healthcare disparities amongst people of color have been exacerbated as a result of higher rates of illness and death among people of color, reflecting the increased risk of exposure to the virus due to pre-existing living, working, and transportation situations, increased risk of experiencing severe illness if infected due to higher rates of underlying health conditions, and increased barriers to testing and treatment due to existing disparities in access to health care.

Major platforms like the CDC should strive to increase awareness for health equity and create a safe environment for marginalized groups; governments and people should advocate for change to create a more inclusive environment.

Is Race a social or biological construct?

Understanding the critical drivers of racial inequities in healthcare

Since the fifth century, physicians entering the world of medicine and healthcare have taken the Hippocratic Oath, a code of ethics for medical practice. Though the oath has evolved over history, its promise to “to do harm” (in Latin, “primum non nocere”) remains a core aspect. Yet, despite the millions of doctors and physicians who have made this pledge, racial inequities and disparities continue to run rampant in healthcare, harming many minority communities. For instance, studies have shown that even with the same symptoms and conditions, African American patients are less likely than white patients to receive the needed surgical procedures or medications. Furthermore, minorities have found to be less likely to adhere doctor-prescribed treatment, such as taking medication, and attend appointments, perhaps due to social barriers (eg. lack of access to transportation) or mistrust in the healthcare system due to continued mistreatment. Whether intentional or unconscious, bias and discrimination seeps into the healthcare system, depriving communities of the care and treatment they deserve. To fully understand how to address these inequalities, it is critical to examine the factors that drive them. The critical drivers of racial inequities in healthcare can generally be categorized into four types: provider factors, patient factors, healthcare system factors, and social/structural factors.

When many individuals think of disparities in healthcare, they think of those that stem from biases from healthcare providers, such as doctors, nurse practitioners, hospitals, urgent cares, medical supply companies, and any individual or organization that provides health services. Indeed, biases from healthcare providers can play a large role in why minorities might receive suboptimal care compared to white patients. To elaborate, racial stereotypes and stigmas can result in “victim-blaming”, which is when patients are given inadequate care because they are assumed to be “responsible” for their ailments. In a survey of 53 veteran healthcare providers published in the National Library of Medicine, one provider stated that when diagnoses and treatments are determined, “[minorities] don’t particularly get the benefit of the doubt . . . I think people would be more forgiving of the white patient.”

In addition to influencing doctors’ decisions about patient diagnosis and treatment, biases can also accumulate throughout communication between healthcare providers, due to the presence of stereotypes and unconscious bias in patient labeling. Patient labeling is the process of denoting a patient’s important identification and medical information to allow for communication with healthcare providers throughout a patient’s diagnosis and treatment. Studies have shown that Black patients are more likely to be labeled with stigmatizing language, such as “drug seeker” (an individual who does not have legitimate medical need and only wants drugs) and “frequent flyer” (an individual who is abusing the health system). The use of such language rather than more neutral terminology can perpetuate stereotypes and prevent patients from receiving the care they need later on.

Moreover, patients’ own behavior and tendencies can also drive inequities in healthcare. A history of negative experiences can cause patients to develop distrust towards the healthcare system, reflected in non-compliance towards medical treatment and medication, as well as avoiding doctors’ appointments. For instance, minority group members who feel judged or discriminated against by the system have a higher likelihood of delaying needed and preventative measures (such as diabetes treatment). Furthermore, studies show that patients belonging to minority groups may inaccurately communicate their personal and medical information to healthcare providers, out of fear of conforming to negative stereotypes. Additionally, due to distrust, patients sometimes disregard physician feedback out of fear that it is biased, or question the validity of their test results due to wariness regarding the motives of their healthcare providers. Ultimately, these factors are largely caused by centuries of inequality towards minorities, both within and outside of healthcare, and must be addressed by healthcare professionals as well as patients. Some important steps to helping establish a more open, trusting relationship between patients and physicians is to firstly, address the implicit biases of healthcare providers, and secondly, to improve healthcare literacy across all communities.

In addition to the providers and patients, faults within the healthcare system as a whole are a critical driver in racial inequities in healthcare. Limited resources that promote equity and inclusivity, such as interpreters, can exacerbate existing barriers for minorities to access healthcare. Not only can an interpreter improve communication and avoid misunderstandings, but they can also make patients feel less anxious and build confidence and trust between patients and providers. Other issues, such as a lack of diversity in the healthcare workforce and disparities in health insurance access, also increase inequity.

Finally, social factors and systemic racism are critical, yet often overlooked, causes for inequities in healthcare. Due to disparities in socioeconomic status as well as discriminatory practices such as redlining, the options for healthcare services, such as clinics and hospitals, are often limited and of lower quality in minority neighborhoods, hindering the level of care these communities can receive. Furthermore, many drivers of social and economic disparities also influence inequality in healthcare. Geography, for example, causes disparities in access to fresh and nutrient-rich foods (eg. food deserts), physical exercise and recreation, transportation, high-quality education, employment, housing, and more — all of which significantly influence health.

Racial inequities in healthcare is the product of many factors and influences: For the healthcare system to truly make good on the promise to “do no harm,” these disparities must be addressed on an individual, system-wide, and societal level.

Health literacy is critical in addressing healthcare inequities

Each day, millions of people head to the doctor’s office for an appointment, hoping to find out what is ailing them and how to alleviate it. However, for many of these patients, it is difficult to understand whatever test results, instructions for medication, or insurance forms that the doctor presents them with. In this situation lies the issue of poor health literacy, which is when the health-related information organizations provide is not easy for patients to understand. This issue continues to disproportionately affect communities of non-English speakers as well as those who are low-income or a part of older generations.

Limited health literacy remains a barrier that hinders individuals’ from getting the treatment they need. Studies done by organizations such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have demonstrated that those with limited health literacy are less likely to use preventative measures (such as getting flu shot or a mammogram), more likely to struggle with managing chronic illness including asthma and diabetes. Furthermore, not fully understanding a doctor’s instructions can lead to making dangerous mistakes when a patient takes medication or treatment.

Providing audiences with efficient access to information about public health and healthcare allows them to make more informed decisions about their health. Yet, according to a report by the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), only 12% of American adults are proficient in their ability to make informed health-related decisions. To combat this, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) outlines a series of three goals for improving nationwide health literacy in their Health Literacy Action Plan: sharing accurate, accessible, actionable health information; ensuring clear communication; and incorporating health literacy curriculum in schools, from the preschools to the universities. To make information more inclusive to all populations, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that patient forms and printed materials, such as medical history forms, insurance forms, and at-home care instructions, be translated into plain language rather than legal and medical prose as well as be provided in multiple languages.

Take this quiz to test your own health literacy skills!

The role of insurance in healthcare

Despite the fact that access to affordable healthcare is a fundamental human right, it is still a significant problem in the United States. Even though America has one of the most sophisticated healthcare systems in the world, its healthcare is also the most expensive.

The cost of healthcare in the US is still rising, and during the previous ten years, prices have increased by an average of 4% annually. The average American spends 40% more on healthcare than any other country. This is an average of over $12,000 a year per American – a cost many people cannot afford, even with partial insurance. 31% of America’s households without full health insurance carry medical debt.

The truth is that with such expensive rates, many people across the country need adequate insurance. In some cases, a person has no access to insurance at all. When healthcare services are only available to those who can afford them, those with lesser incomes and fewer resources go without critical medical care.

Individuals of color – particularly Black and Hispanic Americans – disproportionately lack access to affordable health insurance. African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to lack health insurance than white people, which raises their risk of worse health outcomes.

But for most people who cannot afford health insurance, it is simply because it has not been made available to them.

People living in middle-or low-class neighborhoods are much less likely to have complete healthcare plans than wealthier people – yet these neighborhoods are often grouped by more than just a household’s average income. When deciding what neighborhoods to consider “rich” or “poor”, racial bias plays a significant role.

Statistics have shown that racial minorities often remain in the same neighborhoods. This unfairly brings down the value of these neighborhoods, making it harder for a person of color to show that they live in a trusted area. Noting this, insurance agencies may be more hesitant to supply a person of color with health insurance.

Not only could this lack of insurance lead many into debt, but it is also completely unfair.

The Constitution states that “health care, including care to prevent and treat illness, is the right of the people and necessary to ensure the strength of the Nation.”

Even if healthcare is available, it is expensive to the point where one can only afford it if they rely on insurance. Depriving someone of this insurance sets them up for financial ruin if they ever need the hospital.

In the end, a person who winds up in the hospital should focus on healing; they shouldn’t have to worry about how to pay for their treatment without insurance.

Health and the community

In the community healthcare setting, the primary doctor should be your safety net when push comes to shove. Yet for 30 million uninsured Americans, that safety net is nonexisting. Even so, nearly half of those people are uninsured people of color.

According to the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA), there is a considerable gap in mortality rates between older White and Black adults. The divide has significantly increased in suburban regions as there is less access to affordable care options. In further investigations, the National Institute of Mental Health findings suggest that “about 1 in 5 adults-51.5 million people-lived with a mental illness in 2019.” Amid concerns for the outcome of uninsured individuals, there is help available.

In a recent article by the Independence Blue Cross, insights suggest that while Philadelphia is home to many firsts in the field of medicine, it has some of the state’s worst health outcomes. The state of health in the brotherly city has the lowest-ranked health outcomes and factors. Philadelphia has the highest poverty rate, staggering over 1 million. While the social determinants range from financial situations to access to healthy food and experiences of discrimination, Philadelphians below poverty face the consequences of health inequity daily.

In a partnership with The Philadelphia Tribune, the educational campaign “Our Community, Our Health” is in collaboration with the Urban Affairs Coalition and the Mother Bethel Church on the Ending Racism Partnership. It is with the utmost importance that local organizations partner up to fight racial inequity, as all human beings deserve proper and adequate access to treatment.

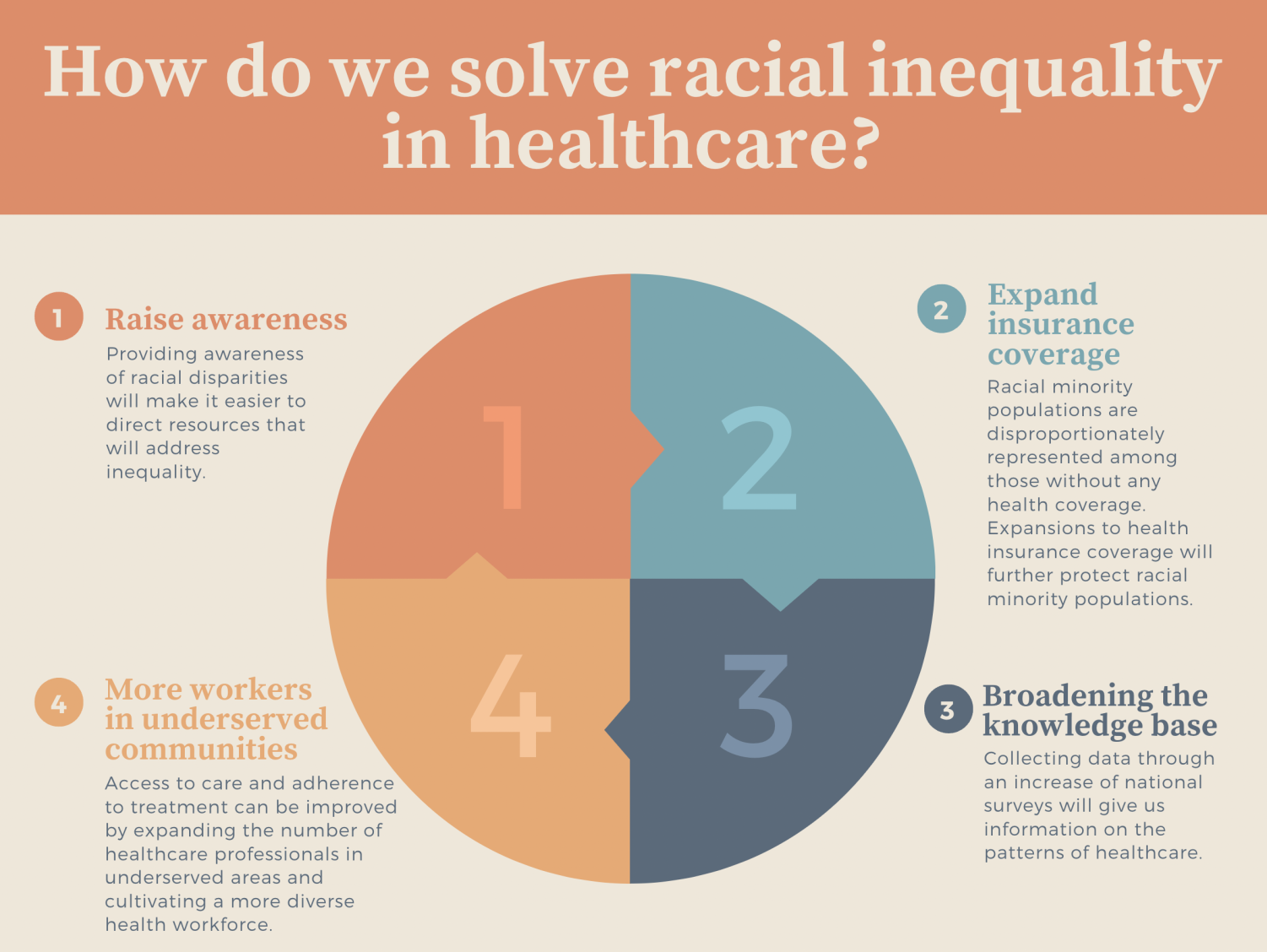

How do we solve racial inequality in healthcare?