A look into college entrance exams around the world

November 22, 2022

Around the world, college entrance examinations play a pivotal role in deciding the future and success of students. As the United States’ SAT becomes considered less with changes like submission optionality, foreign entrance exams including the Chinese Gaokao, the Turkish YGS and the South Korean Suneung continue to have more influence than ever on students’ daily lives. Continue to read for a glimpse into the exams that provide definite opportunities— and repercussions— in students’ everyday lives.

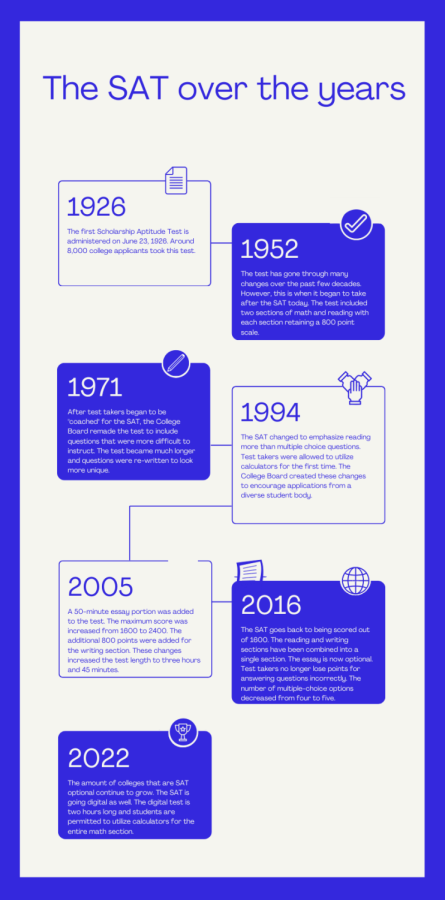

The SAT has gone through various changes throughout the years

The SAT wasn’t always the mind-numbing, stressful and extensive test it is now. The Scholarship Aptitude Test was first introduced in 1926 and functioned as a reliable predictor of a student’s college performance. Over the course of its ninety-six years of existence, the test has undergone various adjustments and modifications making it more challenging and competitive. In the past twenty to thirty years, many changes have been made to the SAT. Some of these modifications aimed to prevent cheating whereas others were designed to encourage high school curricula to emphasize particular subjects.

In 2005, the SAT arguably faced its most significant change yet. Not only were its analogy questions removed, but the maximum score went from 1600 points to 2400 points. These 800 points were added to the writing, reading and math sections. A required essay was included as well with the purpose of prioritizing writing across the United States. All of these changes created a total test time of 3 hours and 45 minutes.

As of March 2016, the score range reverted back to the original 1600 points, the essay requirement was removed and points were no longer taken off for wrong answers. Prior to this change, a “guessing penalty” existed that subtracted ¼ of a point per incorrect answer. Other minor changes included swapping out unnecessary vocabulary words for more commonly used words and dropping the amount of multiple-choice question solution options from five to four per question.

Recently, students have been offered the opportunity to take the SAT digitally through a computer at an administered test center. Changes come with the digital test as well. Instead of the three hours, students will be given two hours to take the test; each section will be slightly shorter than the original SAT. Also, according to the College Board, the reading section will consist of one-question reading passages that cover a wider range of topics typical of the literature students will read in college.

While specific elements of the SAT have changed, the way the SAT is perceived has changed as well. Years ago, a student that scored 1500 out of 1600 would be meritorious and potentially newsworthy. Yet today, scoring 1500 is recognized as an impressive but somewhat common score. The standards of what a “good” SAT score is has risen every year.

Because many students were unable to take the SAT due to COVID-19 regulations and lockdowns, many colleges made submitting scores optional. Since then, there’s been a growing number of colleges that don’t require an applicant to submit their SAT score. Another reason universities are beginning to make the SAT unrequired is to balance out students with economic or racial grievances.

Since its creation in 1926, the SAT has been a reliable indicator for students of what their college performance may look like and which colleges they deserved to attend. For nearly 100 years, numerous modifications have been made to keep the tests timely and efficient. From its changes in scoring to its test-optional initiatives, it’s difficult to predict what this test will look like in upcoming years.

SAT timeline

Many United States colleges switch to test optional

In the past, high schoolers began the first step of the college admissions process during their junior and senior years: the college entrance examinations. Typically studying for months ahead of time, students would sit for the SAT or ACT, hoping to achieve a score to impress colleges.

However, this is not necessarily the case anymore. Starting with students entering college in the fall of 2021, many colleges chose not to require entrance exams. The reasoning behind this change was in part due to the cancellation of most entrance exams in the spring of 2020 in response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Over two years later, many colleges choose to keep the submission of exams optional. As test centers have now reopened, COVID-19 no longer stands as a reason for colleges being test-optional. Thus, the question in the air stands: “Why are so many colleges still test-optional?”

A direct effect of colleges going test-optional— and, most likely, one of the major deciding factors for colleges choosing to stay test-optional— is the drastic increase in the number of applicants. For example, Harvard University saw a record number of applicants for the class of 2025. 57,435 students applied— a 25% increase from the 43,330 applicants the previous year. As for the class of 2026, over 61,200 applied— another 7% increase from the class of 2025.

When colleges go test-optional, students who would not have applied because they did not have the target test score can apply without submitting a score. As a result, more applications flood into top colleges.

Although the colleges receive more applicants, they still take in the same amount of students. Thus, as colleges go test-optional, their acceptance rates tend to drop.

Colleges have also chosen to stay test-optional due to recent criticism of the entrance exams. This criticism circulated for years prior to the pandemic causing some schools to begin going test-optional.

The biggest critique of standardized entrance exams is that, although their name may say so, standardized entrance exams do not give a standard representation of all students. Some students simply are just not good test takers.

Emily Boyle (‘23) said, “I don’t think my scores accurately reflect my knowledge.”

Entrance exams have also been proven to put students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds at a disadvantage. Those who have the financial means to afford expensive, private tutors typically score better on entrance exams.

“I think that there are clearly evident issues with equity in standardized testing, as demonstrated by well-researched correlations between wealth and success on standardized tests,” Aiden Rood (‘23) said.

In correlation with Rood’s statement, Forbes reported in 2021 that a student’s average combined SAT score from a family income of less than $25,000 was about one hundred points lower than a student from a family income of $100,000 or more.

Test-optional does not mean students are completely giving up on entrance exams, however. With thousands of colleges not requiring entrance exam scores this year, many students still plan to send in test scores. Out of 103 East seniors, 55.3% said they plan to submit their scores to colleges and 29.1% said they plan to submit scores to some colleges and apply without test scores to other colleges.

As it has been three years with the majority of colleges being test-optional, some colleges have begun to announce their plans for the future.

Colleges like Harvard University— which announced the decision to remain test-optional through 2026— have already confirmed their commitment to staying test-optional for upcoming years. Many colleges such as Washington University in St. Louis, Cornell University, the University of Michigan and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have announced that they will remain test-optional for 2023 and 2024.

On the other hand, some colleges have chosen to return to the traditional requirement of entrance exam scores. These colleges include all Florida public universities (as decided on by the state of Florida), all Georgia public universities (as decided on by the state of Georgia), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Georgetown University.

This test-optional era of college admissions appears to benefit students with lower test scores. However, some people are skeptical about just how beneficial this policy is.

Former Dean of Admissions at Franklin & Marshall College Sara Harberson writes in her blog, “[colleges] simply are allowing students the choice on whether or not they report scores. But every college wants to brag about how high its test scores are for admitted students. High test scores still matter to them— big time.”

The decision on whether or not to submit test scores depends on every student’s unique situation. When it comes to colleges being test-optional, there is no “correct” answer.

As test-optional policies are constantly changing, time will only tell what this means for the future of entrance exams.

East students on college entrance exams

China’s Gaokao

“One month before I took the Gaokao, I lost about 12 pounds….my hair on the back of my head… half of [it] got gray.”

“I still have nightmares that…I could not finish the test, even now after ten years.”

The Gaokao, the only college entrance exam in China with a reputation that has spread internationally, occupies 10 million students’ lives each year. It is a painstaking test-taking process, wrought with years of dreaded anticipation, preparation and mental and physical impacts for Chinese high schoolers.

The nine-hour test is administered only once a year in early June— and students’ scores solely determine the college they attend. The Gaokao is out of 750 points and consists of six sections, including Chinese literature, math, foreign language (typically English), and three subjects under liberal arts or science, depending on the test taker’s choice. The liberal arts section is split into history, politics, and geography, and the science section contains physics, chemistry, and biology.

While American college entrance exams have become less significant, the performance in the Gaokao completely decides students’ futures. And that is why, for roughly a year, this test will completely overshadow their daily lives— with a rigorous schedule consisting of hours of intense studying and mock testing.

Guolong Zhu, an assistant professor at Fairleigh Dickinson University, took the Gaokao in 2006, preparing for the exam in one of the best high schools in his province of Shandong.

“My focus since in primary school has always been focusing on the scores [and] preparing for the test.”

While the main preparation for the Gaokao takes place during the third and final year of high school, Chinese students have basically prepared since the day they were born. Rather than being educated in different subjects, the Chinese school system is based on teaching students the material that will be tested in the Gaokao. The entire third year of high school is used solely for the preparation of the Gaokao.

“We [had] finished all the high school materials in the first two years. In the last year, the third year, we only did reviewing,” said Zhu.

The preparation is strenuous and long, starting at 7 a.m. in the morning and ending at 10 p.m., which is repeated for the rest of that year. Wedged in the schedule, there are two lunch breaks. Besides time built in for studying, teachers also give lectures, reviewing problems and common mistakes students might have made on mock exams. Saturday afternoons are free, yet most students use this time for further studying. And once a month, students can have a day and a half off.

“The feeling [towards the Gaokao] was really complex. I loved it but it was like a nightmare to me…I spent so much time on it,” said Zhu.

There are several differences between college entrance exams in the United States and the Gaokao in China. American students prepare for the SAT or ACT outside of school, while most, if not all, of the preparation for the Gaokao is done in school, leaving little to no time for outside tutors.

“In order to get into college in China, the score in Gaokao is the only thing. You don’t need those services or extracurriculars or sports, nothing else. Just the score,” said Zhu.

Yet, in America, it seems that extracurriculars and skills are one of the leading influences on American students’ success in college applications. In China, students get one chance a year to get into their dream college—one chance to excel. If they do not score well on the test, then they must wait until the next year to retake it.

“I do have some friends that did not get good enough scores so they just decided to review for another year and took it again,” said Zhu.

Furthermore, the Gaokao is designed to give equal opportunity amongst the provinces by accepting the same amount of students from each province into a school. This, however, often leads to major competition in providences amongst students. Zhu’s providence, Shandong, is one of the most competitive for the Gaokao.

“I got a score [in the] 98 or 99 percentile in my province but I was only able to go to the university with a national ranking [of] about 30 or 40.”

Each practice test counts. Each day and night counts. Each point counts. If Zhu had scored 8 points higher, from his original score of 618 to 626, he could have gone to a school that was 12th in terms of national ranking.

“I got a 618; it’s a number I still remember. Because the score was so important, even now I still remember the scores of many of my friends.”

The Gaokao is considered one of the largest priorities in the Chinese education system and society. For the two to three days of the exam, the traffic and streets of mainland China are limited to facilitate the students taking the Gaokao.

Despite the physical and mental drawbacks that Zhu has stated, he believes that the Gaokao is not flawed to the point of removing it entirely from Chinese society.

“In China, the way that Gaokao [works] is probably the best way. In China, if [they do] not solely rely on the score, but rather with some [extracurriculars, it can be] unfair for those people with less resources.”

Zhu believes that for the exam and its high academic pressure to change, Chinese culture and society themselves would have to change.

One thing remains clear: the Gaokao will continue to tout its reputation of high academic pressure for present and future students.

An interview with YGS test taker Mustafa Teber

Türkiye’s YGS

“Life equals 180 minutes?”

For years, activists for educational change in Türkiye have touted this slogan among others as the hallmark of their opposition to Türkiye’s national exam for higher education, abbreviated in Turkish as the YGS (Yuksekogretime Gecis Sinavi). Indeed, this exam, held once a year, every year for Turkish high school seniors is the ultimate and only determinant for college admissions in the country. A high score could mean entry into one of the top universities in the country, access to lucrative career fields and the admiration of peers and relatives, while a low score could result in decreased future opportunities and a humiliation that leads some students to contemplate even suicide as a reprieve.

From as far back as they can remember, Türkiye’s high schoolers must revolve their life around the national exams. In order to attain a high score, most find it necessary to begin studying doggedly during their freshman year of high school. Special weekend and afterschool cram schools are filled to the brim with students in pursuit of their desired scores. Some are self-motivated. Others are driven more by the pressure of parents, friends and the perception of wider society. In any case, the exams require a long period of preparation, and those who put off studying until their junior or senior years usually find themselves in grave trouble.

This all leads to a host of mental and social problems among Turkish youth. Instead of spending time socializing with friends or pursuing special interests outside of school, students instead find themselves spending nearly every spare minute studying and studying and studying. Conversely, in the United States, extracurricular activities and special interests receive much attention when it comes to college applications. The pressure put on Turkish students leads inevitably to widespread cases of depression, anxiety, self-doubt and various other ramifications. Some even lean towards suicide. In 2017, a senior who was denied entry to the exam after arriving a minute late committed suicide in her home. That same year, another student, who received a lower score than anticipated, committed suicide. The dark truth festers on— student suicides in Türkiye over the YGS are occurring.

For Drexel sophomore Mustafa Teber, who moved to the United States from Türkiye two years ago to pursue his college career, the YGS is not a desirable method of higher education determination.

“I don’t think the Turkish method is…a good way at all. There are many ways to criticize it…you probably learn [math and science concepts] better but I think it’s not all that necessary,” he said. “The American way prepares students to be more well-rounded individuals…they can spend more time on themselves…their family, their friends.”

And yet, proponents of the exam system argue that the YGS provides benefits as well. For one thing, low-income students receive a chance via their exam scores to elevate their status and lives. In addition, proponents argue that stress and fatigue occur everywhere in education and college admissions and would continue even if the YGS was removed. This contention does not seem to be fading anytime soon.

This is the story of Türkiye’s national college admission exams. With both its ups and downs, the YGS national exam will continue to reign over Turkish higher education until the unforeseeable future. For high school students living in Türkiye, there is only one option: study for those 180 minutes— and your life.

South Korea’s Suneung

On the third Thursday of November, the country collectively comes to silence with halted airports, military training and construction sites, delayed openings of the stock market, banks and local stores, and special lookouts by police and taxis. These momentary suspensions are enforced across South Korea in consideration for all the high school students taking the nine-hour college entrance exam, the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT), most often referred to as “Suneung” (수능).

On this day, high school seniors head to school to take the notorious exam that will soon determine their future. With such a crucial test on the line, nationwide precautions and courtesies are shown throughout the community; taxis and police officers offer to drive tardy students and citizens start their day later to prevent traffic for the test takers. Sick or injured students are granted the opportunity to take the test in their relative hospitals with inspectors and nearby care. Parents and guardians of the students are often found in churches, temples or other religious buildings throughout the day, praying for their children.

The test promptly starts at 8:40 a.m. and ends at 5:45 p.m., a nine-hour test marathon. Suneung is divided into six sections: Korean, mathematics, English, Korean history, subordinate subjects and Chinese or a secondary language of choice.

Although the day may seem like an ordinary exam day, the preparations that come behind this test are quite abnormal. Behind this exam are years of prior planning and countless hours of studying. Simply attending and learning from school curricula will not do the job of receiving a recognized, or even accepted, score by colleges.

A significant part of a Korean student’s life involves Hagwon (하권), or private educational institutes. South Korean families spend over 18 trillion Won, or $15 billion, on private education annually, tripling the average country’s expenditure and marking its peak to any other country in the world. There are nearly 100,000 Hagwons in the country with over 80% of both primary and secondary students attending these private academies about six times a week.

Children are introduced to this strict academic lifestyle as early as elementary and middle school. Being placed with high expectations at such an early age, they begin preparing for this exam years ahead. A day in their life typically includes self-studying in the morning, classes from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Hagwon to follow until 10 p.m. and self-studying at night.

Beyond their studies at school, at Hagwon and at home, the students must also build their endurance for the exam. As the exams test their test-taking abilities and time sensitivity, students must adapt to the long hours of focus and practice mock exams.

“[Test administrators] don’t make tests for kids to learn, they make tests for kids to fail,” says Yoobin Nam, a current Korean high school senior preparing to take the Suneung on November 17th, 2022. She comments on the great obstacles of adjusting from American to Korean education, believing education in the United States is fairly easy in comparison to the rigorous academic life in South Korea.

Suneung was created to differentiate the top of the class. As the test is designed to make it nearly impossible to earn full points, nine students of the half-million test takers have achieved perfect scores in the 2018 Suneung, highlighting the exceptional difficulty of the exam and its rarity of a perfect score.

With the exam primarily conducted for university admission, higher scores promise a higher chance of being admitted to a more prestigious college. Especially for those aiming for a perfect score, the top students strive and compete for the Sky universities: Seoul, Korea, and Yonsei University. These reputable schools are seen as the “Ivy League Universities” of South Korea.

With limited spots in the workforce of South Korea, universities ultimately determine students’ ease of finding a job, and therefore, as many see it, their future.

Having their future at risk, the cycle of academics for the students continues and is the greatest factor in causing teenagers stress and burden. It is no coincidence that suicide is now the number one leading cause of death for people between the ages of 10 to 30 in South Korea. The non-stop hours of studying and learning, the overwhelming pressure from parents and relatives and society’s academic standards all contribute to the overwhelming stress that the young community experiences.

This highly competitive reality all ties back to the nine-hour exam. And this accepted reality almost justifies the preparation they must build their entire lives for the exam. This exam is Suneung.