The faces behind the masks

October 28, 2021

As the word returns to normal as the pandemic continues, it is important to reflect upon the deep-rooted impacts of the pandemic. The pandemic has had global impacts, and it is important to acknowledge the troubles and experiences of different populations. From those with mental disorders to the men and women who make up the United States military, we have all been impacted, and this multi-media package seeks to uncover the unique experiences that demonstrate human resilience at its utmost.

Covid-19 demonstrates racial inequity within the health care system

Courtesy of The New York Academy of Sciences

Longstanding issues within the healthcare community lead to racial discrepancies during Covid-19

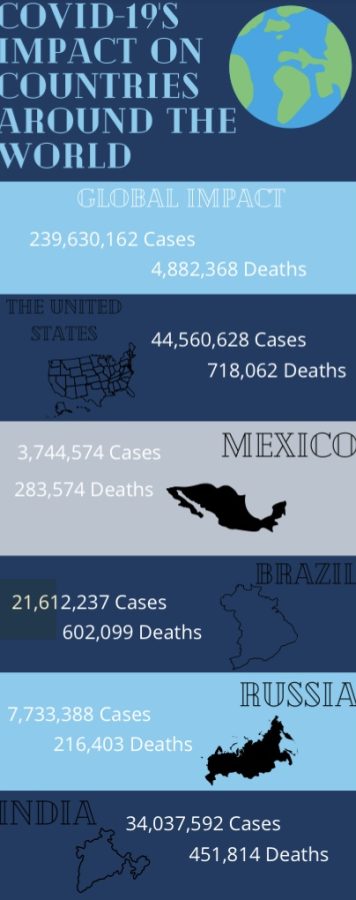

COVID-19 ravaged the entire world and caused the deaths of millions of people. Every nation will forever remember the struggles the virus caused and the immense amount of loss. However, many communities in the United States have felt the impact of COVID-19 greater than others due to ongoing racial inequity within the healthcare system.

Overall, minorities within the United States faced far greater rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in comparison to white non-Hispanic persons at alarming rates. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), African Americans faced 2.8 times the amount of hospitalizations and two times the number of deaths than Caucasian people. Native Americans and Alaskan Natives faced 3.5 times the amount of hospitalizations and 2.4 times the number of deaths. Similar numbers have been reported by the CDC regarding Asians, Hispanics, and Latinos.

A study performed by John Hopkins Medicine revealed that in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, African Americans contributed to 70% of COVID-19 related deaths but only made up 26% of the county’s population.

The significant COVID-19 related death rate discrepancies between minorities and white people are due to a number of factors. Typically, minorities make up the majority of essential workers, such as jobs in factories and public transportation, due to their socioeconomic status. This means that minorities are facing more exposure on a consistent basis. In addition to the higher risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, minorities are more likely to spread COVID-19 due to their living situations.

For example, many African American and Hispanic people live in multigenerational households. According to the Pew Research Center, 29% of Asians, 27% of Hispanics, and 26% of African Americans live in multigenerational households in the United States. This causes crowded living conditions, which can prevent adequate hygiene measures and the ability to self isolate when necessary. As a result, those who live in multigenerational households become exposed to the virus more often than those who do not. The CDC reported that “Hispanic and Black adults were 60% more likely than non-Hispanic white adults to live in households with healthcare workers”, who are at extremely high risk of contracting COVID-19.

When COVID-19 afflicts minorities the inequity within the health care system exacerbates the already present issues within their communities. Throughout history, the United States has developed a foundation of distrust within the medical community with people of color due to a history of discriminatory patient-provider interactions and unequal treatment.

In 1932, the Tuskegee Institute monitored 600 African American men, some with syphilis and some without. Instead of treating them with penicillin, researchers provided no medical treatment which resulted in the death of many men and allowed for both spouses and offspring to contract the disease. This, along with other instances of discrimination within the health care system, helped to develop a deep-rooted wariness within the African American community, which was exemplified through the COVID-19 outbreak. When this lack of trust exists, people are less likely to seek out medical assistance when needed or trust the information being provided by the medical community. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on health issues, white people have received the Covid-19 vaccine at a 1.2 times higher rate than African Americans.

Latina women also faced unscrupulous interaction with the medical community through forced sterilizations. The Smithsonian Magazine reported that “in the first half of the 20th century approximately 60,000 people were sterilized under U.S. eugenics programs.” Young people of color within the working class were deemed “unfit” to reproduce and were targeted to be sterilized. Latinas and Hispanics, in particular, were sought after because they were “hyper fertile” and were institutionalized. During the time, Latina women were sterilized at a 59% higher rate than non-Latinas. Other ethnic minorities, such as African Americans, Native Americans, and other immigrants were also targets for sterilization.

In the present-day health care system, African Americans often face racism from their provider and are sometimes not treated equally with white patients. Countless patients around the nation have reported that they haven’t received the health care they need due to the color of their skin. This can be witnessed through the fact that pregnant African American women are dying at three to four times the rate of non-Hispanic white women and African American infants are dying at twice the rate of non-Hispanic white babies.

The apparent racism within the health care system throughout the United States’ history still enacts consequences today. Due to the inability of the healthcare system to leave bias and prejudice on the sidelines, minorities faced countless more deaths throughout the pandemic. In order for the lives of every United States citizen to be protected, the health care system needs to establish trust with all minorities.

An unlikely home

Tony Henderson is standing casually on the driveway of Jessie Huang’s house, hands in the pockets of his butterfly-decal jeans, wearing a loose sweatshirt and a soft smile. One can not possibly tell from his appearance that six years ago, Henderson did not have a place to live. His story is an instance that sheds light on a kind deed that can sometimes restore one’s faith in humanity.

In the midst of this new mode of living during the pandemic, there has been a population largely overlooked – the homeless. With many shelters closing, social services being reduced, and help largely diminished, it is difficult to dismiss the consequences that these changes have made on the homeless population.

For Henderson, who was once homeless about six years ago, he considers himself lucky. In the midst of the pandemic, he found shelter in the unexpected home of Jessie Huang.

To find a temporary place to stay at night, he would alternate between his friend in Blackwood’s home and his construction boss’s home.

“If I didn’t find a place to go, I wound up riding the bus all night sleeping,” said Henderson.

So, how did he and Huang meet each other?

Four years ago, at a food distribution service in Camden for his ministry, Huang asked Henderson to help him set up the food. Afterward, Henderson would come weekly and help him. Because of Jessie’s background as a real estate agent, Henderson asked him if he knew of any places for him to live.

“I asked, ‘You know somebody who has a room for rent…and [Jessie was] like, I can get you a place to stay,’” Henderson elaborated.

A few weeks later, Henderson was offered a room in Huang’s garage to live in, and began living there permanently.

At first glance, one can see the usual room furnishings in his makeshift room in the garage. There are two refrigerators, a freezer, a bed, and cabinets that extend to the back.

“I’m not out where nobody can hurt me or harm me,” said Henderson.

When he is not at the garage, Henderson helps around the house. Whether it be trimming the lawn, painting a table, or taking out the trash, He helps out with chores as part of his living arrangements. Besides helping out around the house, Henderson also works in construction for a few days a week.

“I can’t just sit around and lay around. I do my own thing and go to work,” Henderson emphasized.

Henderson believes in giving back to the community that once helped him. He volunteered at Cathedral Kitchen, washing dishes or cleaning the kitchen. Now, he goes weekly with Huang and Alex, Jessie’s son, to distribute living necessities including food, clothes, and hygiene products in Camden.

“When I do stuff like that, it keeps me encouraged. And I’m not feeling like I’m just standing around doing nothing,” said Henderson.

Henderson attributes his progress with meeting Huang.

“I could be in Camden right now, sitting in the streets like the rest of ’em, in tents and stuff, laying places, under bridges, in the back of alleys,” reflects Henderson.

After almost four years of living with Jessie and his family, Henderson has formed close relationships with them.

“I enjoy [Jessie] and Alex…they like my two buddies: Alex on my left, he on my right,” said Henderson laughing.

When asked if he would continue to live at Jessie’s, Henderson responded with a smile, “I can’t ask for a better place…it beats nowhere.”

During the pandemic, although social distancing may keep people physically separated, a single act of kindness can connect people during this time. For Tony Henderson, Huang has provided a home, not as a stranger, but as a friend and family member.

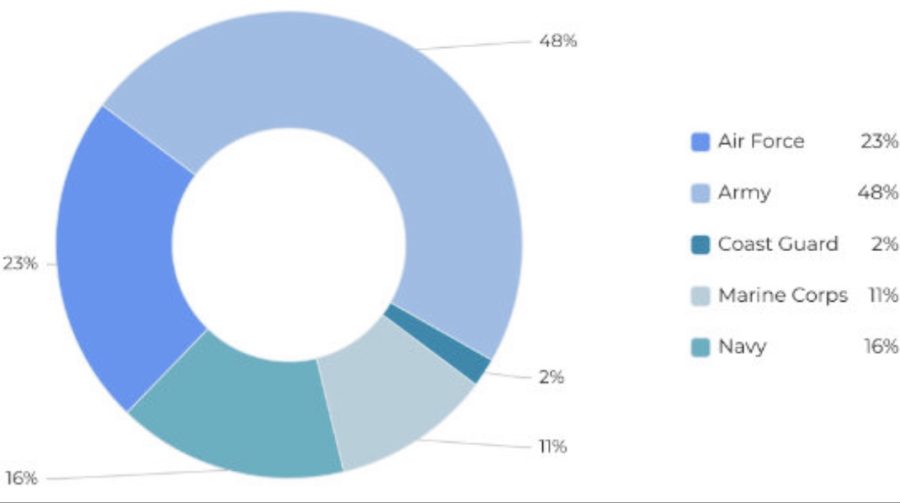

The United States military during the pandemic

Courtesy of the National Military Family Association

The percentages of mlitary families who whose wellbeing was affected by the pandemic.

COVID-19 drastically upended the lives of nearly everyone within the United States. Throughout the country, millions of people died, battling the dangerous disease in crowded intensive care units and understaffed hospitals. At first, with a lack of information regarding COVID-19, the country entered a stage of hysteria. Schools sent their students home, employees laid-off workers, and the economy froze as everything went online. Millions of people flocked to grocery and convenience stores, raiding the shelves and purchasing dry goods, medical supplies, and other basic necessities. In recent months, this reality has largely changed, especially due to the work of the United States Defense Department. Yet while many commend the work of the military, the detrimental effects COVID-19 had on our nation’s soldiers remain overlooked.

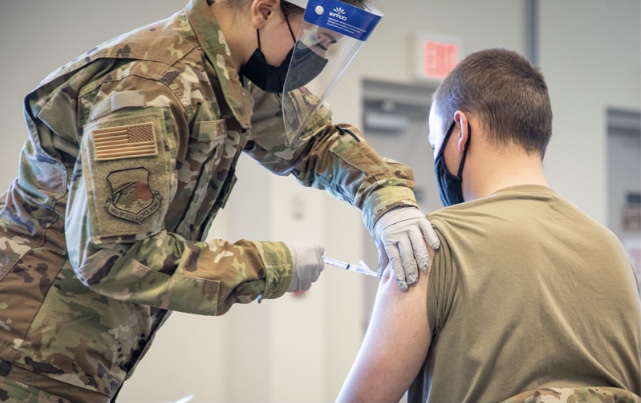

According to the United States Defense Department, “scores of military employees are involved in administering and dispensing doses of vaccinations around the country. Military employees have worked tirelessly to allocate vaccine doses from drug companies into doctors’ offices and hospitals. The Defense Department helped set up vaccine test trial sites and issued contracts that procured swabs, syringes, needles, and other medical supplies that medical personnel needed to combat the virus. Troops also manned understaffed nursing homes in addition to figuring out the logistics of vaccine distribution. In New Jersey, according to the New Jersey National Guard, military personnel are saving lives. They are also coordinating vaccine registration, directing traffic in vaccination sites, and scheduling vaccination appointments.

“The reason why I put on this uniform along with my troops is being able to serve the community – our uniform says U.S. Airforce, whether it’s refueling a jet all the way downrange in the Middle East or being able to give out vaccines,” New Jersey National Guard Captain Jishua Ye said.

Many military personnel are young, such as Captain Ye, who is just twenty-eight years old, which makes them less likely to endure the most extreme effects of the virus. However, according to The Washington Post, military personnel prior to the pandemic often lived in bases with “ideal conditions for the rapid spread of infection.” Furthermore, many military exercises involve putting soldiers in close contact with each other and training with foreign troops. Thus, the Pentagon restricted military movement and minimized training activities that cause troops to come in close contact, in addition to creating other policies to address the potential spread of the virus within the armed forces. As though, according to the Washington Post, these policies come at a cost: reduction in military readiness.

It’s not just policies that have affected military readiness over the past year and a half. When Covid-19 disrupted global supply chains in March of 2020, the military became worried that they would not have enough supplies, such as food, vehicles, and weapons to even be able to go to war if needed. Many of the vehicles the military needs to go to war are complex and require high maintenance. However, many of the employees who work on these vehicles were unable to show up to work, due to the virus. Others chose not to show up to work, for varying reasons, such as fear of infection, which further hindered the military’s efforts to have the best possible military readiness, according to the United States Government Accountability Office. The virus has also hindered military recruitment efforts: army enlistment fell by about 50% in the early days of the pandemic. In June of 2020, Maj. Gen. Frank Muth, head of the Army’s recruiting command, noted that the virus put the Army behind its enlistment goals. Thus, the military began investing more in their recruitment efforts, at the taxpayer’s expense. The Army offered up to forty thousand dollars to special forces and intelligence collectors, linguists, and other specialized recruits. A two thousand dollar bonus was also offered to qualified recruits on certain enlistment days.

Still, according to the Associated Press, in August 2021, military deaths related to covid increased by one-third, and over thirty service members died. As a result, the military made a decision to mandate the vaccination of its service members. The risk of covid to the military, according to Pentagon spokesman John Kirby, “could affect America’s ability to defend itself.” General Mark Milley said that “getting vaccinated against COVID-19 is a key force protection and readiness issue” for the military as well. Without a ready army, the United States becomes more prone to attack and susceptible to danger.

As the long-awaited return to normalcy becomes a reality, many of the issues including the lack of protection and sourcing crucial materials the United States military faced in the early months of COVID-19 have been resolved. While the whole nation suffered from the novelty of the deadly virus, several months later, and proper protocols established allowed for a smoother transition into normal lives. Now, the Defense Department is working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the State Department to ensure the safety of service members and the American people. While the effects of the virus had devastating effects on the army, America hopes for a brighter future, where the armed services can finally return to their full capacity.

Student Perspectives

One of the first changes to life during the pandemic was the institution of online learning, which continued over an extensive period of time. Now that school is returning to normal, students are quickly adapting back to the ways of in-person learning, but not without struggles.

The pandemics effect on mental health

Until recently, the term pandemic was only heard of in sci-fi movies and public health textbooks. Yet, 18 months ago when the world flipped upside down, it began to best describe our day-to-day lives. As per recommendations from top medical professionals to lower covid exposure, social isolation became the reality for millions of Americans. To some, while the initial “two weeks off of school” sounded like a vacation, others feared the threat of coming to terms with the new reality. For starters, the heightened stress about getting sick, spreading the virus, and reducing the overall risk is at the forefront of everyone’s minds, especially those who suffer from anxiety. In an effort to reduce social contact to stay safe, mentally ill people around the world are facing the repercussions.

Along with anxiety, surging rates of depression are closely related to the social isolation of the pandemic. The combination of uncertainty, whether it may be jobs at risk, the loss of a loved one, increased isolation, and overall restrictive behavior in comparison to daily life prior to the pandemic. With regard to schools in the United States following government-mandated virtual learning from the memorable weekend of March 13th, 2020 to the end of the school year, children and adolescents experienced the lack of social interaction necessary in their development.

Through the universal practice of social distancing, the loss of human contact and connection changed the way we live our lives. From 9-5 desk jobs with commutes to Zoom meetings for multiple hours to a day in pajamas, the societal work expectations greatly diminished from the typical idealities of “normal”. For those with underlying mental health disorders, symptoms of anxiety, depression, and obsessive thoughts have heightened significantly just to name a few. Take Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): a chronic, long-lasting disorder in which a person has uncontrollable, recurring thoughts (obsessions), and behaviors (compulsions) on which one feels the urge to act on. Adding the pandemic into the mix led to increased awareness all around, whether it may be excessive hand washing to avoid contracting the virus or recurring thoughts aiming to reassure the anxiety. Coping with mental illnesses takes time, treatment, and adjusting. Yet, adding new triggers such as constant news headlines with information about staggering COVID-19 deaths or breaking news about new information can throw someone over the edge with fear of contracting or spreading the virus.

On another note, according to the National Institute of Health (NIH), the effect of the pandemic may precipitate the development of eating disorder behaviors, along with exacerbating the vulnerable population, such as those with body image and eating concerns. The National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA) reported experiencing a 68.1% increase to their helpline in the fall of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, prior to the pandemic. With the world flipped upside down, the need to take control, aside from various other contributing factors, sparked a surge in eating disorders around the world.

At the same time, as schools were online, there was less control over cell phone use, including the increased absorption of the toxic culture of social media. Consumed by social media posts, comparing, and demand for control, combined with added fear and depression by lack of socialization, it became the perfect storm with all adequate factors adding up. The Wall Street Journal credits the CDC for data of an astronomical amount of mental-health-related emergency visits up 90% in 2021. In many scenarios, unfortunately, the impact of COVID-19 on adolescents caused a surge in mental illnesses, ranging from eating disorders to depression, OCD, and the list goes on.

To this extent, the extremely dangerous “side effect” of COVID-19 wasn’t the “long-haulers”, people experiencing COVID-like symptoms after negative test results, but the treatment necessary to return to day-to-day life. While the future is uncertain regarding when the pandemic will fade away into a historic period of our society, the effect of living through a global pandemic has touched on millions of people across the globe, including adolescents suffering from mental illness.

Healthcare perspectives

Many healthcare workers are struggling with the new way of life at work caused by the pandemic.

Alexa Albert

Alexa Albert has been a registered nurse in cardiology for the past twenty years. Interestingly enough, not only has Alexa’s work changed due to COVID, but COVID has become her work. Through specializing in the COVID unit, Alexa became a traveling nurse in February to support the high demand for frontline workers. She explained this process, but simply put, she works in each designated location until her contract is up. Alexa works twelve to sixteen hours every day.

Usually, each contract lasts a few weeks at a time. Safety is a top priority for those working in the COVID unit so, Alexa said she wears a gown depending upon the time duration each nurse stays with the patient. Alexa wears a level four gown being that she spends the longest duration of time with patients. Gowns are numbered one through four, with four being the most protective and restrictive gown. They also wear headgear similar in appearance to a biker helmet. Protecting her face is a shield and an N-95 face covering. Some of these clothing restrictions include the tight sealing that exists with such protective uniforms. The uniform lets in such little outside air, so, nurses find their eyes getting red and dry. It is very difficult for these nurses to get water as they have to remove the entire suit to do so. Alexa shared that something her unit has been doing is making their nurses print a picture of themselves and attach it to the outside of their suit. This way, the patient can see the faces of the nurses all suited up for protection. “The COVID unit is a no visitor allowed area. As morbid as this is, the only area with visitors allowed is for dying patients. And even then they need to be in a suit as a visitor and are only allowed in for a short duration. Overwise, it’s staff only in these units,” said Alexa.

For her, she finds working as a Covid nurse during these unprecedented times has isolated her from her family. “A lot of people don’t realize everyone in my department is actually fully vaccinated and we are fully covered from head to toe, but my friends, where you know, nervous to be around me knowing what I do. It’s sad and lonely to wake up at 4 in the morning, be in a gown all day, can’t eat at the same table at lunch with other nurses, get home until 8:30 at night, and not be able to see friends and family. But I love being able to help.”

She shared with me that she’s grateful to see the effects of the vaccine. “People think the vaccine is political. It’s just been proven to me that working with patients in critical care every day, those that are fully vaccinated heal faster and are much safer than those who didn’t get the vaccine. Being that I work to rescue patients like this, I just see those that are vaccinated having greater survival rates in the hospital. Either way though, whether the patient is vaccinated or not, I honor them and care for them just as good. That is our job.” Alexa said a change from the start of COVID to now is that there has been an increase of younger patients in the Covid unit. She suggests staying physically active and working. “It helps the lungs to open up. Also, people should look to educate on getting vaccinated. But if anyone is experiencing signs of COVID, they should isolate themselves at home and seek medical attention.

MARISA RILEY PIZZI

Marisa works at a private practice in primary care pediatrics as a physician assistant. She has been a PA for the last six years but worked in medicinal research prior, meaning she has spent the last ten years in the healthcare industry.

“Covid has affected work in every single possible way, including just the basics of how I get ready for the day,” said Marisa. Prior to the pandemic, she said it wasn’t uncommon for physician assistants to dress as they pleased. “I used to actually wear real clothes, and try to look nice at work. And now I wear scrubs every day,” said Marisa. In addition to the unified scrubs, all employees in her office must wear an N-95 mask and eye goggles.

Despite the changes in attire, Marisa notes that the biggest change is simply how often COVID is the topic of conversation. “Pretty much every one of my visits talk about COVID in some way. So whether it’s someone that’s there for their annual physical because they’re 13 years old, which happens regardless of COVID, we often talk about if they had COVID in the past two years. Or if a child has a fever, even though I think it’s an ear infection, is it an ear infection because they had a viral illness that was COVID?” Whether it is a small part of the visit or not, Marisa says she cannot remember a time since the start of the virus where it was not mentioned at least once in a session. Her office is also now requiring patients to wait in their car instead of in a waiting room.

Additionally, different times of the day are meant for different types of visits. Those that are going for well-visits enter in the mornings. Those that are sick must schedule an afternoon appointment. “Before we used to just mix it up where everyone comes when they want. Now, we have times of the day dedicated to separating those that are sick and those that are healthy, to avoid any cases of incidental transmission,” said Marisa. While there are no mandates for COVID restrictions implemented in her office, Marisa said everyone she works with decided to get the vaccine. Another struggle for frontline workers has been limiting their emotional responses to people that complain. “I feel like a lot of parents are very frustrated with the global pandemic, as am I. Sometimes policies are frustrating to them. And I feel like as healthcare workers, we’re often the people that parents will criticize.” Somewhat jokingly, Marisa pokes fun at these types of situations that she goes through on a daily basis: “I’ll have parents say things to me, ‘So you’re telling me that I had to take off the next two days to stay home with my kid because there’s like chance that it might be COVID.’ Like, yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying.” She finds these situations awkward but says it is her job to go along with the guidelines set in place by the CDC.

While no official rules were put in place for workers to separate themselves during lunchtime, that has seemed to be the pattern at Marisa’s workplace. “It is our job to care for those with COVID, so generally people don’t congregate in the lunchrooms or hang out without masks outside of work, simply because it’s what we believe in,” said Marisa. “I already am someone who spends my time giving vaccines to kids because that’s part of general primary care pediatrics, so I already knew vaccines work. But, it’s nice to have reiteration on that,” said Marisa. Building on this, the second biggest takeaway from all of this is the changing nature of medicine. Marisa says she needs to be prepared with answered questions anytime a parent raises a concern. “Parents read something on a bulletin board on Facebook and it’s my job to give them the specific data on why that is correct or incorrect, not just say, well, there wasn’t a you know that’s not true. I should be able to prove it with data.” Her final statement was this- “whether you agree or not with the words of a healthcare worker, what they said always comes from a place of trying to do what we think is the safest thing for the patient.”